By Laura Ewald

Photos By Daniel Dubois

Underneath the awning of a cafe

tucked into a strip mall on the outskirts of Nashville

is a wooden plaque, easily missed by the untrained

eye: “The best songwriters in the world

pass through this door.” A bold statement

even in a city big on bold statements, it is nonetheless

true—from Garth Brooks and Trisha Yearwood

to the poets behind today’s biggest country

(and pop, rock, Latin, and instrumental) hits,

countless songwriters and recording artists call

the Bluebird Cafe home.

Founder Amy Kurland, BA ’77,

is one of the most influential people in what

many consider the music capital of the world.

I Feel Lucky

Kurland runs, as singer-songwriter Karen Staley

puts it, “the Ellis Island of Nashville,”

hosting open mic nights, auditions, and booking

new writers and artists to perform at the Bluebird

and with affiliated touring shows. She has rolled

out the welcome mat for the unheard and unsigned

since 1982 when the Bluebird opened far off “Music

Row,” the area southwest of downtown Nashville

that houses the big dogs: labels, executives,

managers, studios, and the Country Music Association,

one of the music industry’s most powerful

trade groups. Despite its less-than-commercial

location, the Bluebird is the heart of the industry.

“Nashville more than ever is considered

the songwriting capital of the world, and we are

the Capitol dome,” Kurland says. “We’re

the place you can see the process happening.”

|

|

As the songwriting process unfolds at the Bluebird,

so do all the other steps that happen before a

hit reaches the radio, TV, and the Internet—audiences

respond, writers collaborate and revise, execs

and managers take meetings, artists record demos,

and marketing teams put together the whole package.

But you don’t play at the Bluebird without

making it past Kurland.As the gatekeeper to Nashville’s

most respected songwriter showcase, her taste

and point of view shape who plays, who listens,

what sells, and what the world hears.

Fortunately for the world, Kurland has a good

ear. Countless songwriters and artists warmed

up at the Bluebird—Kathy Mattea, Faith Hill,

and Vince Gill among them. But nowhere is Kurland’s

influence more obvious and universal than the

career of Garth Brooks, who became a featured

writer and performer at the Bluebird in the mid

’80s. Brooks heard the song that would become

his first hit, “The Dance,” penned

by Tony Arrata, at the Bluebird, when Arrata performed

it in a showcase.

“I could not picture my life without the

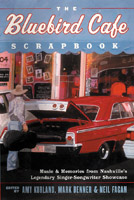

song or the songwriter,” Brooks writes in

The Bluebird Cafe Scrapbook: Music & Memories

from Nashville’s Legendary Singer Songwriter

Showcase, which Kurland co-edited with Mark

Benner and Neil Fagan. “The Bluebird gave

me both.”

Brooks made it big, in some categories outselling

Elvis and every other individual performer in

history—his sales are comparable to those

of the Beatles. And after Brooks, country music—all

of music, actually—will never be the same.

His boundless appeal helped to break down genre

barriers and opened the cross-promotional, collaborative

doors that remain open today. Mass appeal is what

the labels still look for and is in part what

makes collaborations such as rap star Nelly and

country favorite Tim McGraw’s “Over

and Over” so successful. Broad appeal catapulted

a number of female solo country artists—namely

Shania Twain, Yearwood, and Hill—into the

limelight in the ’90s, paving the way for

the young female voices of today.

Songwriters are

stars at the Bluebird, which celebrates

the craft.

|

|

“The whole music business is absolutely

in turmoil—it’s a wonderful thing

because radio stations still are genre-directed,

but nothing else is,” Kurland says. “Big

labels know they can’t afford to be in one

genre. The big labels every day become less powerful.

You so seldom hear about someone unknown being

signed to a major label; but you so often hear

someone say, ‘Go to my MySpace page, I’ve

gotten thousands of page views.’

“Luckily, I’m not in the thick of

having to pick the next big star. We are here

for the songwriters to show off their wares. These

songs happen before anybody categorizes what they

are, which is great because a good song can take

10 years to get on the radio.”

In a way, Kurland’s voice is heard in

the music born at the Bluebird. “I wish

I could sing and play guitar, and I cannot. But

I get to have a career in the music business that

makes me part of the good songs that are on the

radio; part of having audiences go crazy at shows,”

she says. “That’s almost as good—maybe

better—than being the one doing the singing.

I’m part of making the music.”

Music and performance run in Kurland’s

blood. Awards her father, Sheldon, won for work

on Music Row grace the walls of the venue among

headshots of songwriters and artists who perform

at the Bluebird. Shelly Kurland Strings, which

he founded, was a highly regarded group often

requested for recording sessions on Music Row.

Kurland’s mother started a theater group

near where the Bluebird now stands when Kurland

was growing up. Kurland’s parents supported

the Bluebird from the beginning, though her father

warned her not to include a stage in the cafe,

as he thought people wouldn’t want to be

bothered with music while they ate.

Kurland’s upbringing played a hand in

developing an important tool in recognizing good

music—her gut.

Following her intuition has served Kurland well,

at least in the long run. Growing up in Nashville

and in upstate New York, Kurland came to GW because

friends were nearby and she was interested in

politics. “We made so much use of the city.

I was in the museums, on the Mall, and in Georgetown

every weekend,” Kurland says. During her

sophomore year, Kurland became interested in cooking

(a skill she developed by using butter and sugar

packets pilfered from the Thurston Hall cafeteria

to make cookies) and the restaurant business.

She decided to finish her bachelor’s degree,

double-majoring in American studies and American

literature, largely, she explains, because the

coursework was flexible and fit her broad interests.

“The fact is that it wasn’t my intention

at all, but an American studies degree fits in

perfectly with a career that’s about country

music and songwriting,” Kurland says. “I

think that education, that way of thinking about

things, has made me a better person to understand

country songs, and that’s what I do for

a living, I’m around songwriters.”

After graduating and briefly operating a bakery

in Nashville, Kurland attended the Culinary Institute

of Washington. “I went back to Nashville

as a GW grad and a cooking school dropout,”

Kurland recalls. “After hanging around nightclubs

and learning to love country music at a hot dog

place, I opened a restaurant as a naïve 25-year-old.

I credit no sense or anything else for my success,

just flat-out stupidity and bravado. The musicians

I knew from bars said, ‘Why don’t

you put in a stage?’ and I agreed because

it gave me a chance to be around more guys who

play guitars.”

In Nashville, when it comes to music venues

with open mics, it’s not “if you build

it, they will come” so much as “if

you build it, they will help you build it, and

then they will come and keep coming.” From

the very first night, the Bluebird has been packed.

With success came responsibilities, and Kurland

found she had a lot to learn about running a business.

She took classes in small business management

at a community college in Nashville; there, she

picked up a piece of invaluable advice.

“I learned that you’ve got to find

one thing to be, and to be the best at that one

thing,” Kurland says. “So we focused

on showcasing good songwriters.”

That simple decision changed the country music

industry.

Stars Go Blue

|

Garth Brooks’

audition sheet, autographed for Kurland.

|

Though Kurland says she didn’t see a dime

from running the Bluebird until after it had been

open for six years, its impact on audiences and

performers was immediate and deep.

“The Bluebird completely changed the way

writers were viewed on Music Row. It also brought

the creative people who had been in the shadows

for so many years to the attention of the public

who had never thought about who wrote the songs

they heard on the radio,” artist Karen Staley

says. “At the Bluebird people come to listen

to music—not to just use it as background

noise for conversation. People really respond

to the purity of the creator of the song interpreting

it the original way it was intended.

“Everyone loves to play the Bluebird,”

she continues. “That’s why everyone

from T. Graham Brown to Faith Hill to Garth Brooks

and scores of others knew that if they were going

to get their name out on the Row, the place to

be seen was the Bluebird. It was automatic clout.”

Kurland, too, has built a solid reputation on

and off Music Row. She’s proud of her venue

and the artists it showcases. And while many are

quick to point out its untapped potential (read:

expansion and commercialization), Kurland definitely

thinks the ’Bird ain’t broke.

“We get asked the question about expanding

all the time, but nobody’s ever offered

me the money to expand,” Kurland says. “I

decided years ago that it is best for the people

who play here to play in a small environment.

“We really work with brand-new songwriters

right off the turnip truck, and you don’t

want to put them in front of 300 people. Even

more, you don’t put them in a room that

seats 300 people, but only has 10 people in it.

Seventy-five to 100 seats is perfect. If only

25 people show up, it doesn’t feel empty;

and if it’s crowded, everybody thinks they’re

having a great night.”

Because of its reputation and popularity, the

Bluebird has had to cut back on its large-scale

open auditions, holding them only four times a

year. Open mic nights on Mondays are always packed.

But Kurland is quick to point out that hers is

not the only place in town to gain exposure—the

Bluebird is part of a Nashville network.

“You

come in on a Monday, put your name in the hat,

if you get your name drawn, you get to play two

songs for a great audience, and right away, you

get your career started. People will hear you,

talk to you, offer you advice,” Kurland

says. “But there are other open mics around

town, and I’ve never told anybody otherwise.

I tell people to go play everywhere, play all

over town, and being here is just part of the

process. Nashville is Songwriter University.” “You

come in on a Monday, put your name in the hat,

if you get your name drawn, you get to play two

songs for a great audience, and right away, you

get your career started. People will hear you,

talk to you, offer you advice,” Kurland

says. “But there are other open mics around

town, and I’ve never told anybody otherwise.

I tell people to go play everywhere, play all

over town, and being here is just part of the

process. Nashville is Songwriter University.”

While she wants to keep the Bluebird physically

small, Kurland enjoys exploring its potential.

“I’m interested in expanding my

reach. There are other ways to reach people than

just running a bigger club in Nashville.”

The Bluebird sponsors nationwide tours, hosts

numerous charity benefits, develops partnerships

with travel destinations including Disney World

and a ski resort in Montana. It has been the setting

of a weekly music television program on Turner

South. This was the fourth summer the Bluebird’s

music was featured in a series at Robert Redford’s

Sundance Resort. In 1994, Paramount Pictures released

The Thing Called Love, starring Sandra

Bullock and Samantha Mathis, about a group of

singer-songwriters based at the Bluebird.

Though the film—and the occasional reporter—perpetuated

a few stereotypes about everyone in Nashville

wearing cowboy hats, Kurland has enjoyed the Bluebird’s

visibility and successes. And she’s left

its momentum unchecked. “I’m an old-fashioned

owner who doesn’t have a phone bank, doesn’t

have Ticketmaster, and doesn’t have a glass

case in the front with T-shirts in it. But if

you’re willing to wait on the phone with

a busy signal to get tickets, and if you can get

in the door, we want you here and we hope you

come back.”

Long Time Gone

Part of what keeps music lovers coming back

to the Bluebird is the chance to hear new music

not yet on the radio. What is on the radio right

now by and large leaves Kurland cold.

“Country music is in the middle of a stupid

phase, a phase that is probably on its way out,”

Kurland says. “The part of ‘country

culture’ that a lot of music chooses to

celebrate right now is ‘let’s get

drunk and drive our cars real fast.’

Rivers Rutherford

“in the round,” singing hits

he wrote for artists including Tim McGraw.

|

|

“You hear a song like [Montgomery Gentry’s]

‘Hell Yeah’ or [Gretchen Wilson’s]

‘Redneck Woman’ right now, basically

a song that says, ‘I don’t care what

you think of me—my kind of people are running

this country’—and in some ways, that’s

great, because everybody deserves their day in

the sun, and people who respond to that music

perhaps have felt ignored for a long time. But

I think our country, and music, is swinging back

to caring about the environment, taking responsibility

for our children, and I would be surprised if

we don’t start to hear more songs about

taking care of each other.”

This isn’t the first period of dramatic

change country music has experienced, nor will

it be the last. Everything from the invention

of the radio to world events have changed the

music, and country’s ebb and flow toward

and away from its “roots”—if

those can be traced and quantified—is a

familiar theme. Whether country is or belongs

to genres such as folk or bluegrass is debatable.

Whether it will be annexed by pop is, to some,

a frightening thought. Blurred genre lines, while

making for better sales, also make it harder to

answer the question: Who, and what, is country?

Wherever the music has been, it’s been

celebrated in Kurland’s venue. Wherever

the music is headed, the foundation of change

will be laid at the Bluebird.

When the Lights Go Down

On a Friday night in August, when the stars

are out at the Grand Ole Opry with a crowd 4,000

strong, the hottest ticket in town is at the Bluebird,

where four men and their guitars are sitting in

the center of the room, telling the stories of

their lives—and your life, too—to

a packed house of about 100. Rivers Rutherford,

Brett James, Cole Deggs, and Jim Collins write

songs for Martina McBride, Keith Urban, Carrie

Underwood, and Tim McGraw. If you’re lucky

enough to catch a performance “in the round”

at the Bluebird, you’ll hear the stories

behind the songs from writers who love to perform—and

even for diehard country fans, to listen is to

be surprised.

Take Collins’ “She Thinks My Tractor’s

Sexy,” a big record for Kenny Chesney, with

its relentless percussion, unapologetic twang,

and a healthy dose of pop gloss. Stripped down

to the songwriter and his guitar, with backup

vocals from the crowd, there’s a charm and

a tongue-in-cheek humor that got lost in big label

translation. Songs that have been exhausted by

airplay—and ubiquitous American Idol covers—are

reborn, and the men who are singing them aren’t

stars by Billboard standards, but are deeply appreciated

by the audience. (Appreciation at the Bluebird

often comes in the form of beers and tequila shots

sent over by fans.)

|

An open-mic performer

on the Bluebird’s small—but

legendary—stage.

|

Calling Kurland the “den mother”

of established and up-and-coming songwriters alike,

Rutherford says part of the magic of the Bluebird

comes from putting the songwriters front and center—after

all, many of them first came to Nashville in hopes

of becoming recording artists. “She gives

people behind the scenes a chance to be in the

spotlight,” Rutherford says. And the crowd

is in the spotlight as well, singing along, calling

out requests, drumming on tables and clapping,

becoming a part of the music.

Sitting at small, candlelit tables, leaning

against the bar, and packed into three mismatched

church pews over in the corner, tonight the crowd

is made up of music lovers from California, tourists

from Chicago, singer-songwriters, and Clay Bradley,

vice president of artists and repertoire of Columbia

Records, who is gamely fielding cracks from Rutherford

and crew.

In a few hours, the human condition has been

sung and strummed: love, heartbreak, sex, and

laughter; children, God, America, and war. This

is the Bluebird. And—movies, books, articles,

tours, stars aside—this has been the Bluebird

since the doors first opened: music, stories,

writers, audiences who love real music. And while

Kurland has always recognized and executed opportunities,

nights like these will never change. The past

and present of music are found within the Bluebird’s

walls, and the future is in the notes ahead, songs

unwritten.

|