By Lyle Slovick

|

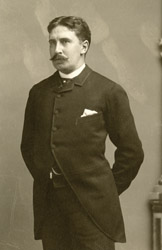

This portrait of George

Yost Coffin was taken around 1890.

|

Many fascinating characters have

been linked to GW in the 185 years since its founding.

Alumnus and Washington Post political

cartoonist George Yost Coffin is notable for the

characters he created and the diaries he kept

that describe life in Washington during the Civil

War.

Coffin graduated from Columbian College (the

original name of The George Washington University)

with an A.B. degree in 1869 and a Bachelor of

Laws degree in 1871. While a law student, he also

was an art tutor. Upon completion of law school,

Coffin became a clerk in the Revenue Marine division

of the Department of the Treasury, where he remained

employed until his death. This position provided

him a fixed income and the freedom to create his

art.

Coffin’s career as a political cartoonist

began in the mid-1870s with The Washington

Chronicle, the city’s first illustrated

newspaper. After its demise, he contributed to

Harper’s Weekly, Puck, and Judge

until 1883, when he took a job as an artist for

The Washington Hatchet, another short-lived

weekly paper. Puck and Judge

were popular political publications of the late

1800s and early 1900s, with colorful satirical

illustrations of the leaders of the period. Like

Harper’s, they had a wide audience.

During this time Coffin also contributed to a

number of papers in Washington and elsewhere,

including The Washington Star, Sunday

Herald, and The National Tribune.

In 1891, he gave up his freelance work and became

the official cartoonist for The Washington

Post.

Coffin was known

as a humorist without malice, though he

covered timely political topics.

|

|

Coffin’s cartoons were nonpartisan. An

article from the Dec. 5, 1896, Columbian Call

student newspaper quoted him as saying: “Every

political situation has half a dozen comical sides

to it, according to the view point.” His

humor was wholesome, the article went on to say.

Said one who knew him, “He was a most charming

man at a social gathering. A born gentleman, a

gifted conversationalist, and a narrator with

hardly a peer in his circle.”

Coffin’s thorough knowledge of Washington,

its customs, and its characters gave his cartoons

a particular flavor. His work was without malice.

It was his rule never to make his cartoons offensive

or grotesque. “You need not make a man odious

or repulsive in order to caricature him,”

he once remarked. Even those he cartooned were

not offended and often called upon him for a friendly

interview. Among Coffin’s “victims”

were Grover Cleveland, William McKinley, and Theodore

Roosevelt, as well as Alexander “Boss”

Shepherd, head of Washington’s territorial

government. Coffin also illustrated a number of

books and was a dramatic critic for The Washington

Post, Sunday Herald, and Critic.

Coffin’s papers were donated to the University

in 1926 by Isabelle Solomons, a family friend,

and are maintained and made available to researchers

by the Department of Special Collections and University

Archives in Gelman Library.

|

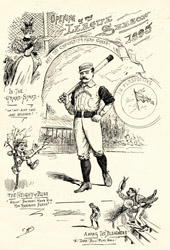

An avid baseball player,

Coffin wrote frequently about the sport

in his diaries.

|

Coffin was born in Pottstown, Pa., on March 30,

1850, and came to Washington with his parents

when he was 8 years old. He began a diary a year

later and continued it off and on until 1868.

The four diaries he kept record the folkways of

19th-century Washington and offer insights into

the political climate of the nation, as interpreted

by a precocious teenager.

Coffin’s connection with Columbian College

was established at an early age. George Whitefield

Samson, who became president of Columbian College

in 1859, was the pastor of the E Street Church

in Washington, and sometimes preached at the church

Coffin and his family attended. Other Columbian

College students and faculty members are mentioned

in the diary in regard to church services and

Sunday school.

Coffin’s childhood days were filled with

baseball, books—he mentions reading 220

from 1857 to 1868, including Dickens, Bunyan,

Irving, Tennyson, and Longfellow—and drawing

and painting. These interests proved to be lifelong,

as Coffin played baseball during his time at Columbian

College, was an excellent student, and turned

his artistic talent into a profession.

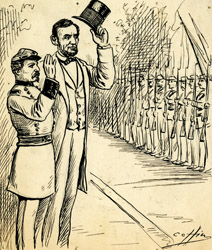

Coffin kept sketchbooks

of doodles and drawings. This drawing was

created after the Civil War and portrays

President Lincoln reviewing troops. Lincoln

visited the Columbian Hospital, located

on the College grounds, on at least one

occasion, in 1862.

|

|

While Coffin’s diaries were sporadically

kept, they do offer insight into life in Washington—and

on campus—during the Civil War. On July

12, 1864, he wrote of trying to go to Fort Stevens,

in the northern part of Washington, with a friend.

There was fighting there, and they were turned

back by guards. Walking home, they observed a

large detachment of troops, prompting Coffin to

observe, “The city undoubtedly is in great

danger. The firing at the forts is fairly audible

in the heart of the city.” Coffin also later

noted seeing troops marching up H Street, yet

the tone of his entries never conveyed a sense

of panic or prolonged tension. In fact, he didn’t

mention military matters much at all, focusing

instead on his daily routine.

Three days later, Coffin and another friend

procured passes to go to the battlefield. They

“started for the field which we soon reached,

we saw the graves of several of those who fell

in the fight, one man buried with a forefinger

left uncovered.” Unfazed, they observed

destruction around them and picked up souvenirs.

They met with three soldiers who “invited

us to lunch with them in their ‘crib’

which they called the ‘Hotel de posh.’”

After sharing a lunch of hardtack, pork and beans,

and coffee, the soldiers went back to work and

the boys returned home. “Our walk home was

a weary one, we being loaded down with about 95

cartridges a piece, besides other weighty trophies.

However we enjoyed ourselves very much.”

|

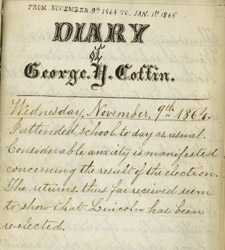

Coffin’s four

diaries date from 1859 to 1868. An entry

from Coffin’s diary, dated Nov. 9,

1864, records the results of the presidential

election, which was the source of “considerable

anxiety.”

|

At the end of the summer, it was time to go back

to school, which for Coffin was the Preparatory

School of the Columbian College. The College had

been founded in 1821 and was composed of five

buildings on “College Hill,” north

of Florida Avenue, N.W., between 14th and 15th

Streets. The Preparatory School played a significant

role in the first 76 years of the University.

It was designed primarily to afford thorough training

for admission to college. Coffin entered in 1862,

and records show that he took courses in geography,

history, Latin, Greek, and algebra, among others.

Tuition was $55 a year. Because Coffin did not

keep a diary during the first two years, we have

no record of his first-hand experiences.

On Sept. 19, 1864, he began recording daily

life at school. Coffin was a member of the Hermesian

Literary Society, serving as editor of its newspaper,

the Casket, in 1863. The Hermesians conducted

debates, which Coffin wrote about frequently:

“I found myself as a debater on the affirmative

side of the question ‘Should suicide be

considered as an evidence of courage or cowardice.’

It was decided in the affirmative,” he wrote

on Sept. 30, 1864. This society had a number of

prominent members in its time, including Otis

Mason, principal of the Preparatory School from

1861 to 1884, and later the head curator of the

Department of Anthropology at the Smithsonian;

John Larner, who served the University for 20

years as chairman of the Board of Trustees; and

Theodore Noyes, who later became editor of the

Washington Evening Star.

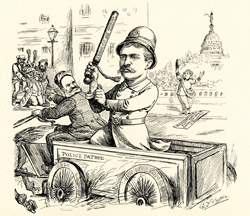

Coffin’s

cartoon “Our Inhospitable Hospitals”

appeared in The Washington Post March 20,

1895. A woman comes to the D.C. public hospital

with her sick child, only to be turned away.

The rules read: “Persons not requiring

the assistance of this hospital admitted

at all hours. No others need apply.”

|

|

As 1864 drew to a close, Coffin often commented

on the presidential race. On Nov. 8: “Today

the election for President takes place, and it

will be decided whether we are to have four more

years of bloodshed, misery, taxation and ruin,

or peace once more spread its wings over our distracted

land, bringing blessings and prosperity in its

train.” A week later he commented: “The

election has passed and we are doomed to another

four years of anarchy & disaster.” It’s

easy to tell who got young Coffin’s vote.

Even though he was no fan of Lincoln, Coffin

reported going with two friends to see the inaugural

procession, which until 1937 was held on March

4. “After having waited for some time in

the mud & rain, in the immense crowd that

lined the avenue, the president or rather his

closely shut carriage (for he was invisible) hove

in sight. He was attended only by his usual cavalry

guard and some of the marshals.” Coffin

noted that the day “opened with floods of

rain but about noon the clouds cleared away. Perhaps

this is ominous.”

As the war was drawing to a close, Coffin devoted

more attention to it in his diary. On April 5,

1865, he wrote of seeing “some terrible

scenes among the wounded who have arrived from

the front at Columbian Hospital.” When the

war began, the government took over the grounds

of the College and used it for two hospitals (the

other was Carver Hospital) as well as for soldiers’

barracks. Despite significant challenges, the

College and Preparatory School continued operations

during the war, and by 1865 the South was in its

death throes. On April 13, Coffin described the

city: “All the public and nearly every private

building are illuminated & tastefully trimmed

with flags, lanterns, wreaths, etc. Many of the

patriotic inscriptions were very appropriate.

Bands are playing, magnificent fireworks are being

set off and the city is a blaze of light…Every-one

is rejoicing at the prospect of peace.”

|

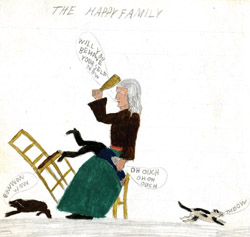

The George Coffin

Papers contain more than 900 sketches plus

many others in scrapbooks. There are a number

from Coffin’s childhood, some dated

as early as 1858, when he was 8 years old.

This one, titled “The Happy Family,”

is from that era.

|

The next day brought horrible news. “At

about 10 p.m. during the third act of ‘Our

American Cousin’ [a play Coffin himself

had seen in February of that year] at Ford’s

Theater, where Miss Laura Keene is playing, a

pistol shot was fired in the private box of President

Lincoln & a man leaped upon the stage brandishing

a dagger, shouted ‘Sic Semper Tyrannis,

the South is avenged,’ rushed out, gained

his horse & escaped.”

The following day, he wrote: “The President

died at 22 min. past 7 this morning. Thus has

our rejoicing been changed into grief.”

On April 19, Coffin walked from his home at 354

New York Ave. to 14th Street and Pennsylvania

Avenue to see the funeral procession, and then

noted that he spent the remainder of the day playing

ball. Life went on for him and the nation.

On Sept. 27, 1865, Coffin began studies as a

freshman at Columbian College. He and his roommate,

Eugene Soper, chose Room 18 on the first story

of the main building as their quarters. Coffin

noted, “The building is being renovated

after its four years appropriation to hospital

purposes.”

President Samson was Coffin’s French teacher.

Coffin became a member of the Philophrenian Society,

another student debating group, and was editor

of its newspaper, the Spectator. The

post-war years are mostly full of news regarding

his studies, his friends, improvements to the

college grounds, a cholera panic, and the daily

routine of life, including his love of baseball.

After final examinations in June of 1866, Coffin

returned to Pottstown for summer vacation, and

the diary entries become sporadic after that.

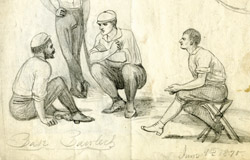

This page of

sketches was drawn by Coffin as a freshman

at Columbian College. It also includes a

note from Nov. 11, 1865, in which he mentioned

hearing a lecture and writing a letter to

a friend.

|

|

On March 3, 1868, two days before going to the

Capitol to see the impeachment trial of President

Andrew Johnson, Coffin made this entry: “Attended

college and said my lessons. Performed likewise

an extraordinary [a]mount of loafing & howling.

The former is an ancient & well known [em]ployment,

which has been popular among college students

& indeed [m]ankind in general, from time immemorial.”

This entry is an excellent example of the sense

of humor found in his writing. In the last few

pages he spoke of drawing, which he had been doing

since a child. Legend has it that as a college

student he frescoed the walls of his dormitory

room with Shakespearean scenes and characters.

They were considered so good that officials spared

them from destruction when the interiors of the

building were painted, and they remained until

the building was razed.

George Coffin died Nov. 28, 1896, of locomotor

ataxia, syphilis of the spinal cord. How he was

stricken with this affliction we do not know.

For the last year of his life he was rendered

an invalid but was said to have remained in good

spirits and hopeful. After he died, his body was

taken from Washington back to Pottstown, where

he was buried in the family plot next to his mother.

He had no wife or children to survive him. What

is left today are extracts of his soul, freely

given, captured, and held fixed on the pages of

yellowing paper in the form of his writings and

drawings. These live on to tell a story of a time

gone by but not forgotten.

Lyle Slovick is Assistant University Archivist.

|