By Matt Lindsay

To many, $1 billion may seem an

outlandish amount of money. But in the realm of

university endowments, that benchmark is becoming

the status quo. At the end of the 2005 fiscal

year, five universities possessed endowments of

more than $10 billion: Harvard University, $25.5

billion; Yale University, $15.2 billion; Stanford

University, $12.2 billion; University of Texas,

$11.6 billion; and Princeton University, $11.2

billion. Harvard and Princeton eclipsed the $1

billion endowment threshold more than two decades

ago.

|

|

As of June 30, GW’s endowment stood at

$962.6 million. The most recent National Association

of College and University Business Officers endowment

survey, released in January, placed GW’s

endowment as the nation’s 69th largest,

between the University of Florida and Syracuse

University. Good company, but not among the endowed

elite. That same survey found 56 schools with

endowments of more than $1 billion, including

several liberal arts colleges with less than 2,000

students, such as Amherst College and Swarthmore

College. Obviously, more money means more opportunities,

but what do these endowment figures mean in practical

terms?

When Stephen Joel Trachtenberg became GW’s

15th president in 1988, the endowment was valued

at about $200 million—its current, nearly

billion-dollar standing reflects increased fundraising

and wise management. At GW’s leadership

retreat in June, Trachtenberg articulated the

importance of the endowment to the University’s

future operations, stating, “If we are going

to prosper academically, we must rely less on

tuition—there is no choice, as I think I’ve

made clear—and more on endowment. Only a

firm financial foundation will allow the University

to remain flexible and first-rate.”

In the last three years, the University’s

endowment experienced tremendous growth, expanding

from about $630 million to nearly $1 billion,

under the leadership of Trachtenberg, Board of

Trustees Chair Charles T. Manatt, Board of Trustees

Investment Committee Chair Russ Ramsey, Executive

Vice President and Treasurer Louis Katz, Vice

President forAdvancement Laurel Price Jones, and

Chief Investment Officer Don Lindsey. Those who

oversee the endowment are now charged with the

task of taking it beyond the billion-dollar benchmark

and keeping it competitive.

Dissecting the Endowment

GW’s endowment is a pool of more than 900

individual endowments, each of which provides

perpetual financial support for a designated purpose.

The endowment sustains professorships, scholarships,

fellowships, research activities, University operations,

and a student investment fund (see following story).

Annual endowment payouts provide universities

with budget support and offset expenses. While

payouts differ, the average university uses about

5 percent of its endowment annually. Thus, hypothetical

“University A” with a $1-billion endowment

will put $50 million in endowment funds toward

its annual operations, while hypothetical “University

B” with a $100-million endowment will have

$5 million annually for its operations—disparity

in endowment size can affect the resources and

services universities offer.

GW does not have a fixed-percentage payout rate;

it uses a complex formula to calculate a payout

rate per unit of the consolidated endowment. The

total payout from GW’s endowment to the

University was more than $36.1 million in 2005.

This payout freed up other funds to support endeavors

including academics and student life.

To Ramsey, BBA ’81, CEO and CIO of Ramsey

Asset Management, “The endowment is your

nest egg; it serves as a safety net for the University.”

Some analysts believe universities are hoarding

money in that nest egg, essentially shortchanging

current students. Ramsey and Lindsey disagree.

“If we spend more than 5 percent, we would

seriously run the risk of eroding and eating into

principal, which means that we’re benefiting

the present constituency at the expense of future

generations,” Lindsey says. “And if

we don’t spend anything, certainly that’s

going to help people down the road, but it means

GW can’t meet its ongoing mission. It’s

a very difficult balance, but one that we constantly

think about and relate back to as we make investment

decisions.”

In basic terms, endowment managers aim to earn

an annual rate of return equal to what a university

spends out of its endowment, plus the ongoing

inflation rate. GW spends about 5 percent annually

and estimates inflation to be 3 percent, thus

the required rate of return is 8 percent.

“If we can make over that 8 percent, then

we’re able to grow the purchasing power

of the endowment, meaning we can provide at least

as much for future generations as we provide today,”

Lindsey says. “But hopefully we will be

able to provide more for future generations than

we can provide today, by continuing to grow above

that long-term expected rate of return. That doesn’t

mean you do it year-in and year-out. Some years

there can be a 20 percent return and some years

there may be a zero percent return. But if you

can try to limit the downside and on average generate

a 10 to 12 percent return, then that’s going

to meet the objective.”

While rate of return goals are consistent across

universities, organizational structure is not.

Universities with smaller endowments often outsource

management. The largest endowments can afford

more employees—Yale has a professional staff

of 20—and several elite universities have

formed wholly owned subsidiaries to manage their

endowments, namely Harvard Management Company.

GW has three professionals, including Lindsey,

dedicated to investment analysis and portfolio

management. The main thrusts of this work are

research—reviewing industry fundamentals,

growth prospects, government regulation, and the

like—and identifying, meeting with, and

selecting money managers. GW employs 35 money

managers to invest the University’s endowment

funds. Although GW’s Investment Office exercises

significant control over the University’s

endowment assets, that responsibility previously

lay elsewhere.

Investment by Committee

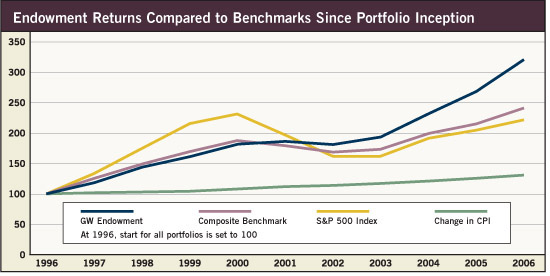

It has been a tumultuous decade for the endowment.

Prior to 1996, endowment management, except for

real estate, was outsourced. That year, the Board

of Trustees Investment Committee assumed control,

administering the endowment for the next seven

years, during which its market value expanded

from around $500 million to more than $630 million.

However, growth lagged behind the average achievement

of 41 “peer” universities and seven

“market basket” schools that GW considers

direct competitors: Boston University, Duke University,

New York University, Northwestern University,

Tulane University, University of Pennsylvania,

and Vanderbilt University.

The years between 1996 and 2003 were turbulent

times for university endowments, and the market

as a whole. The bull market of the late 1990s,

where massive gains could be realized, gave way

to the downturn of 2001 and 2002, where positive

returns were rare. As the size of GW’s endowment

fluctuated, it became clear that a dedicated,

full-time staff was needed to recommend allocation

targets, conduct research, interview money managers,

and provide day-to-day oversight of the endowment.

A New Approach

In April 2003, Lindsey joined GW as chief investment

officer, tasked with creating an internal endowment

management operation at the University. Lindsey

brought 16 years of experience, including stints

at the University of Virginia, and as president

and CEO of the University of Toronto Asset Management

Corporation, where he managed the wealthiest Canadian

university endowment.

At GW, Lindsey initially focused on retooling

the endowment’s asset allocation. He recognized

the need to change asset weights and to diversify

into additional asset classes to produce more

stable and predictable returns. This meant reducing

real estate holdings and the reliance on traditional

asset classes, such as U.S. stocks, bonds, and

cash, while expanding into new asset classes such

as private equity, commodities, and hedge funds.

Lindsey says that if assets are correctly balanced,

this diversification strategy can reduce risk.

“I certainly believe in putting fairly

high-risk strategies into the portfolio. But the

important caveat here is you don’t look

at risk in a portfolio on a stand-alone basis.

The real art is combining risky strategies together

so that you can reduce the overall risk because

the strategies are not correlated to each other,

they balance each other,” Lindsey says.

Lindsey also overhauled the University’s

investment process. The new approach mirrors the

target asset allocation, with a renewed focus

on research, due diligence, and investment monitoring.

Lindsey says the new investment process establishes

a unique approach to endowment management.

“We start the process with looking at

major global themes and where we think the growth

opportunities will be over the next five to 10

years. It is really a top-down approach that leads

us to have a view about different areas of the

economy where we see growth opportunities,”

Lindsey explains. “Once we identify those

areas and find a way to invest in that concept,

then we go look for managers to implement that.

We think this is an attractive approach going

forward because, unlike in the ’80s and

’90s where we were in a very strong equity

bull market and all you had to do was own the

S&P 500 Index, today it is much more difficult

to find growth opportunities.”

Energy,

infrastructure, and international assets are areas

that Lindsey and his team identified as being

underinvested in recent times, but where one can

expect significant global growth in the coming

years. Energy,

infrastructure, and international assets are areas

that Lindsey and his team identified as being

underinvested in recent times, but where one can

expect significant global growth in the coming

years.

Additionally, Lindsey emphasizes the need for

the University to stabilize the annual endowment

payout. In recent years, GW’s spending as

a percentage of endowment has been closer to that

important 5 percent figure, in line with peer

institutions.

Lindsey also promotes the openness of endowment

operations and dialogue with current and potential

donors; as vice president for advancement, Price

Jones appreciates Lindsey’s efforts toward

transparency. “Wise and transparent management

of an endowment leads people to make gifts to

a university,” Price Jones says. “It

is a hindrance if the endowment is not well managed

and if people are in doubt about how it is being

managed.”

The Proof is in the Performance

In the last few years, the endowment management

approach implemented by University leaders has

produced impressive results. The total value of

the endowment has grown by nearly $400 million.

In the three-year period leading up to June 30,

2006, the GW endowment generated a net annual

return of 18.3 percent, significantly outperforming

the composite benchmark three-year net annual

return of 11.6 percent. During the 2006 fiscal

year alone the market value of GW’s endowment

ballooned 17 percent, from $823.1 million to $962.6

million.

Lindsey, Ramsey, and Price Jones see beyond

the tangible monetary benefits associated with

the endowment’s growth to the intangible

advantages, such as positive publicity and more

opportunity to inspire donor confidence. “When

people make the biggest gifts they have ever made,

they view them as investments,” Price Jones

says. “Donors are putting their money to

use at the University, and they want to know they

are investing in a place that will manage their

money well and support those enterprises to which

they gave the money.”

Yet, for all the recent success, there is more

that needs to be accomplished.

Phil & Jim Bliss/Images.com

Opportunity, Cost

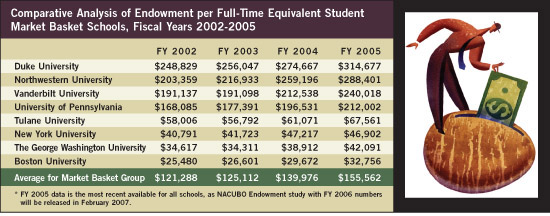

The same NACUBO survey that ranked GW 69th in

the nation in terms of endowment market value

places the University number 228 among private

institutions in terms of endowment assets per

full-time equivalent student. At the end of the

2005 fiscal year, GW’s endowment per FTE

student stood at $42,091, far less than the $1

million-plus sported by Harvard, Princeton, and

Yale. The value of a university’s endowment

per student is reflected throughout an institution,

in diverse areas such as tuition, financial aid,

academic research and programming, and faculty

salaries. Larger endowments per FTE at peer institutions

allow these universities to create unique advantages,

such as waiving tuition for students from low-income

families.

“Endowment per FTE is an important measure

because it determines how much money an institution

is able to allocate per student that attends,”

explains Damon J. Manetta, manager of public affairs

with NACUBO. “Just because an endowment

has a great deal of money behind it does not mean

it has the same buying power.”

GW trails almost all of its market basket competitors

in endowment funds per student. Of the seven universities

previously mentioned—BU, Duke, NYU, Northwestern,

Tulane, UPenn, and Vanderbilt—GW bests only

BU’s endowment per FTE. Schools such as

Duke, Northwestern, Vanderbilt, and UPenn boast

an endowment per FTE that is five times larger

than that of GW. Lindsey estimates that to be

on the same level as its peers, GW would currently

need an endowment valued at $2.5 billion.

Furthermore, GW is not growing at the same rate

as its peers. While the University’s endowment

per FTE student has increased by approximately

50 percent in the past decade, the average endowment

per FTE student growth rate among peer schools

was nearly 150 percent.

“An endowment’s size is important

relative to the number of students it is supporting

and to the amount that a university needs to take

out annually,” Ramsey says. “If you

look at GW versus virtually any of our peers,

our endowment per student is near the bottom.

Alumni need to understand that this endowment

is substantially undersized in terms of needs

of the school.”

Another way to quantify an endowment’s

contribution is to measure the percentage of a

university’s operating budget financed by

endowment funds. In 2005, GW’s endowment

provided $36.1 million toward University operating

expenses, about 6 percent. In comparison, in 2005,

Yale’s endowment provided $565 million to

the university, about one-third of its operating

budget, and Stanford’s endowment contributed

$452 million, approximately 17 percent of its

operating revenue. A more direct competitor, Vanderbilt

University, obtains about 14 percent of its annual

operating budget from the university endowment,

more than double the funding provided by GW’s

endowment.

Although the GW endowment has grown by leaps

and bounds, it still has some ground to make up

to stay in step with peer institutions.

The $1-BillionThreshold and Future Growth

If recent growth trends continue, GW’s

endowment will cross the $1-billion threshold

this academic year. While this is largely a symbolic

milestone, it is significant. After all, it was

only a decade ago that the University’s

endowment crossed the half-billion dollar mark.

In 2004, a 5 percent payout from the endowment

provided the University budget with $34.3 million.

The 5 percent payout budgeted for fiscal year

2007 will provide more than $46.3 million toward

GW operations, $12 million more than just three

years prior.

“The good news is the endowment is at

critical mass. We have a tremendous track record

and a tremendous chief investment officer,”

Ramsey says. “However, we have to watch

carefully the amount of the endowment that goes

into operations and realize that the rate of return

will likely be lower in the future. We can’t

commit ourselves to spending future dollars that

may not be there.”

“Managing an endowment is a delicate balance

between providing financial resources for the

present and for the future,” Lindsey explains.

“That means we have to have in mind not

only preservation of capital so the current constituency,

being the students and the faculty, have resources,

but we also have to think about the fact that

the school has been around since 1821 and it’s

going to be around for another 100 or 200 years

more. It’s hard to think that far in advance,

but we really have to think about the endowment

as being in perpetuity.”

Enhancing the Endowment

Endowment growth in the past decade has been

driven primarily by investment performance. Gifts

accounted for about 14 percent of GW’s endowment

growth between 1995 and 2004, but over the same

time frame, gifts made up roughly 50 percent,

on average, of the endowment growth at BU, Duke,

NYU, Northwestern, Tulane, UPenn, and Vanderbilt.

Investment performance can only do so much—gifts

serve as the catalyst to rapidly vault a university

ahead of its competitors and into the upper echelons.

In each of the past four years, GW has seen

somewhere around $13 to $15 million in annual

gifts to the endowment. Price Jones says she would

like to obtain more endowment gifts for the University,

although oftentimes donors can see a more immediate

impact through other types of giving. Price Jones

says that, in the long term, no other type of

gift is as effective at championing a specific

cause as an endowment, because “an endowed

fund lasts forever.”

“I believe we are rapidly approaching

a world-class investment operation that will help

us grow endowment at the best rate that we can,”

asserts Ramsey. But he agreed with Lindsey and

Price Jones that future endowment growth relies

heavily on both gifts and investment returns:

“The school must dramatically increase the

amount of money that goes into the endowment.”

More than a year ago, Associated Press higher

education writer Justin Pope opined, “The

$10-billion endowment soon may be the new $1-billion

endowment—and $1 billion a mark of mere

mediocrity, not excellence.”

The managers of GW’s endowment are keeping

that prediction in mind as they move forward,

refusing to accept mediocrity and striving for

excellence.

Ramsey

Student Investment Fund Yields Impressive

Returns

|

The Ramsey Student Investment Fund

is managed in part in the Capital

Markets Room in the new Ric and Dawn

Duqués Hall.

Julie Woodford

|

One of GW’s most unique gifts came

in 2005, when Russ Ramsey, BBA ’81,

and his wife, Norma, gave $1 million to

the University endowment to establish the

Ramsey Student Investment Fund. This investment

portfolio is managed by GW MBA students

in the Applied Portfolio Management course,

with insights and guidance provided by professors

Don Lindsey, GW’s chief investment

officer, and Ethan McAfee, director of research

at Ramsey Asset Management.

Students are divided into teams that research

stocks in five different sectors. Each student

is assigned two portfolio stocks within

his or her sector to research and analyze.

After this background work, the student

issues a hold or sell recommendation for

each stock. Equities are added to the portfolio

from the pool of companies that students

propose as buy recommendations, based on

additional research in his or her sector.

While each student must issue a hold or

sell recommendation on two companies and

identify two companies as buy recommendations,

the class as a whole votes on how to proceed

on each stock, with majority opinion ruling.

“We are hoping to teach real-world

skills, i.e. investing in the stock market

and doing it successfully,” Ramsey

explains. “The goal is to start a

culture of attracting high-energy and motivated

financial students who want to learn the

capital markets and money management business.”

The class provides a more realistic environment

because the students are dealing with real

money, which brings more pressure to perform.

“The pressure was high because you

feel personally responsible in front of

everyone in the class,” says Mira

Spassova, MBA ’06, a student in the

Applied Portfolio Management course. “It

is embarrassing when you have not done your

homework and researched the company from

A to Z.”

The portfolio management course “keeps

us at the forefront of finance education,”

Lindsey says. “This is a way for us

to put the students in a situation that’s

designed to be as close to an investment

management operation as possible. And certainly

having real money is the element that does

it for us.”

While the overall performance of the student

investment fund is important, of equal significance

is educating students about the structure

and procedures of an investment management

operation.

In the first year of its operation, the

Ramsey Student Investment Fund certainly

did score. Since its inception in May 2005,

the fund produced a 17.1 percent rate of

return, almost five percentage points above

the rate of return of the S&P 500. In

only 14 months, the assets in the fund grew

from $1 million to $1.2 million.

Lindsey believes the course creates a

process that is educational and which can

perform well in practice. In the future,

he hopes students will be exposed to a wider

variety of investment vehicles as the fund

expands into more asset classes; more complex

strategies, including derivatives; and international

markets.

“Even though it takes many years

of practice to develop portfolio management

skills, these students are being introduced

to that practical element in a way where

they feel challenged because there are real

dollars at risk,” Lindsey says. “The

overall objective is to contribute to the

success of business education. We’re

just one component in trying to continue

to move the MBA program forward.”

—Matt Lindsay

|

|