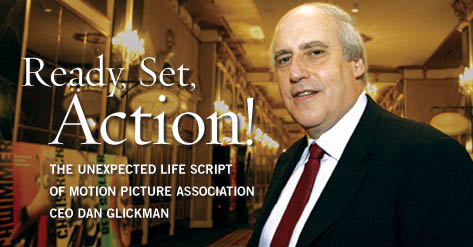

Motion Picture Association of America Chairman

and CEO Dan Glickman, JD ’69, at ShoWest,

an annual Las Vegas convention of theater

owners, March 15, 2005. Glickman took over

in 2004 from one of Hollywood’s best-known

figures, Jack Valenti, who had led the MPAA

since 1966.

Isaac Brekken/APWWPBy Mark R. Smith

When he reminisces

about the six-block trek from his boyhood

home in Wichita, Kan., to the Crest Theater,

Motion Picture Association of America Chairman

and CEO Dan Glickman,

JD ’69, must think he’s dreaming

when he contemplates how he’s spending

his time these days.

|

Dan Glickman watches President Clinton sign a farm bill in 1996 in the

Oval Office. Glickman served as agriculture secretary from March

1995 to January 2001.

AP/WWP |

And while work is still “work,” a

dream it might be.

Back then, little could Glickman have thought,

after graduating from GW Law School, winning

nine consecutive congressional elections,

running the Department of Agriculture,

and a stint at Harvard University, that

such an intriguing challenge was still

looming. Then came the call that he had

been named to replace legendary head man

Jack Valenti at the MPAA, the industry’s

most powerful lobbying organization.

The

62-year-old Glickman has come a long way

from his roots in America’s heartland.

After graduating from the University of

Michigan, he moved to Washington to work

on Capitol Hill and attend GW Law. From

there the rest is history. Indeed, his

varied experiences give him a great story

to tell—one that he laced into his

commencement speech to the Law School’s

Class of 2006 in May.

To Glickman, that move east was what might

be termed today as a no-brainer. “I

was always interested in politics, so it

was a natural” to come to Washington,

he says, noting internships he served with

Sen. James Pearson (R.-Kan.) and Sen. Peter

Dominick (R.-Colo.).

While not passing himself off as a gifted

student, Glickman, in fact, graduated with

honors. Every so often, “my shortcomings

as a student would become extremely obvious,” he

says, such as during a course in criminal

law he took with Professor James Starrs. “I

also learned a lot from Professor Jerome

Barron,” who later became dean, he

says. He has kept in touch with Starrs

and Barron, as well as Professor Jonathan

Molot.

After

graduation, Glickman went home and served

as president of the Wichita school board

and a partner in the law firm of Sargent,

Klenda and Glickman; then he returned to

Washington to work as a trial attorney

at the Securities and Exchange Commission.

By that point, he had already acquired

skills that aid him in his present position. “It

is helpful to understand business partnerships,

contract arrangement, property rights,

and antitrust related issues,” Glickman

says, adding that his legal background

makes him able to “pick up [on new

business] a little faster that way.”

Glickman’s next major turning point

was around the corner. At age 31, he returned

to Kansas to run for Congress in 1977 and

won. Then Glickman won the next race, and

the next race, and the race after that.

And many more. In fact, he held his position

until 1995, winning nine consecutive elections

before losing his 10th campaign. It was

then he realized that he was simply “a

Democrat in a state that was becoming Republican.”

He

enjoyed several finer moments in the House

representing Kansas’ 4th Congressional

District. They included serving on the

House Agriculture Committee

and the House Judiciary Committee, where

he was a

leader on technology issues. He also was

a leading congressional expert on general

aviation policy and served as

chairman of the House Permanent Select

Committee

on Intelligence.

Glickman’s agriculture experience

paid great dividends when he was tapped

by President Clinton to be secretary of

the Department of Agriculture in 1995.

Highlights of his almost six-year tenure

included the administration of numerous

farm and conservation programs, the modernization

of food and safety regulations, and the

creation of new international trade agreements

to expand U.S. markets, which proved invaluable

when he accepted his $1.5 million-per-year

position at the MPAA.

At the end of Clinton’s term, Glickman

left the Department of Agriculture in January

2001 and returned to private practice with

Akin Gump Strauss Hauer & Feld in Washington.

In August 2002, he added Ivy League panache

to his resume when he became director of

the Institute of Politics at Harvard University’s

John F. Kennedy School of Government. For

two years, he directed the institute while

remaining a senior adviser with Akin Gump.

Then, suddenly, it was time for the guy

who sees about 50 movies a year anyway

to head “back to the cinema”—but

along a much different path. While his

move in 2004 to lead the MPAA was an unforeseen

occurrence in Glickman’s crystal

ball, it was an even bigger surprise in

the film and television industries, which

are populated by executives who couldn’t

fathom how a former agriculture secretary

could run the powerful film lobby.

Despite those doubts, Glickman felt that

he was, indeed, the right man for the job.

He points to his experience of managing

a federal agency with a $70 billion budget

and 100,000 employees, as well as his ability

to “work both sides of the aisle” to

gain nonpartisan support needed to push

legislation through the appropriate channels.

Another bonus is his knowledge of copyright

law and the process required to get antipiracy

laws through Congress.

It also happens that Glickman knew the

charismatic Valenti, an ex-Lyndon Johnson

aide who led the MPAA for nearly four decades,

from his days in Congress. Valenti also

knows Glickman’s wife, Rhoda. She

was director of the Congressional Arts

Caucus for about 15 years and coordinated

Capitol Hill movie screenings that Valenti

hosted. Glickman also had one more connection

to the film industry. His son, Jonathan,

is a film producer with Spyglass Entertainment

and was mentored by Valenti on his way

up. Among his credits are the Jackie Chan

movies Rush Hour and Shanghai

Knights.

Since he came to the MPAA, Glickman says

his biggest surprise has been realizing “the

enormous impact of the film industry” in

the United States. Yet he is quick to point

out that the film industry was all about “globalization” long

before the word became part of the public

lexicon.

“It’s an enormous export enhancer,” he

says, “and it has the positive balance

of payment surplus with every country that

we do business with. Also, it is a big part

of our country’s international image.”

Glickman says the industry employs between

800,000 and 900,000 workers who range

from actors to directors to crew to employees

of theater companies to the various concessionaires.

Worldwide, the financial impact of box

office business is estimated to be about

$25 billion—and that’s not

counting DVD sales or Video On-Demand purchases.

Of urgent concern, however, is the issue

of content protection, as piracy costs

the industry $3 billion annually. The

MPAA has taken a four-pronged approach

to combat the problem: initiating litigation,

creating educational programs, encouraging

the development of new technologies,

and developing cost alternatives to lower

the price of acquiring content.

Glickman also notes the competition in

the market. First, many U.S. states are

offering “very generous tax incentives” to

keep production within their confines. “Hollywood

still dominates,” he says, “but

the bottom line is still dictated by the

market.”

And then there’s the work that’s

going outside of the United States. But

what is going to other countries, such

as Canada, the United Kingdom, and Australia,

can’t easily be quantified, due in

part to fluctuations in the value of currency.

Given this situation, Glickman is also

mindful of where revenues come from. “We

have to be careful not to take an anti-foreign

view because [people in other countries]

watch our movies,” he says. “This

is why we stress to Congress that the film

industry is important.”

Glickman’s current challenges must

make his days at the Law School seem like

another lifetime. Experiences like moot

court, which gave him practical skills,

are a big part of why he found GW so satisfying.

In addition, “The big joy of going

to law school here was the D.C. experience,” which

included Vietnam protests and the like,

he says. “It all certainly gave [learning

about] law a sense of realism.”

Glickman also reflected back to his childhood

and those quick walks he took to the Crest

Theater, where he “escaped from the

everyday world” for the whopping

price of 25 cents per ticket.

He remembers the landscape from his boyhood

that consisted of the fledgling television

industry and the pleasures of the Silver

Screen, noting that “there’s

so much competition today” for an

individual’s attention.

“In the past year or two, the industry

has flattened,” he says. “I want

to keep people focused on the value of film

and TV as part of their lives. My job is

to make people feel good about movies.”

Mark R. Smith has written extensively

about film and video production while also

focusing on business topics in Maryland

with The Daily Record in Baltimore

and The Business Monthly in Columbia,

Md., which he also edits.

|