Acting Locally, Thinking Globally

New GW institute unites bright minds to advance HIV/AIDS

research.

By Abby Vogel

On Aug. 29, 1981, GW’s Gary Simon diagnosed the first

recognized HIV/AIDS patient in Washington, D.C. More than

a quarter century later, Simon and other GW faculty members

are leading the fight against this deadly virus by creating

an institute that focuses on research, clinical care, and

collaboration among those in the medical community.

The newly created GW HIV/AIDS Institute is a network of researchers

and medical professionals using their knowledge to prompt

studies and provide patient care in Washington, D.C., where

the disease now affects 4 percent of the city’s residents.

Nationally, nearly 1 million HIV/AIDS cases have been reported.

This renewed focus on the epidemic is part of the GW Medical

Center’s strategic plan, which pinpoints HIV/AIDS as

a priority in the university’s diverse and talented

medical community.

“What we found was this enormous powerhouse of science

and talent from basic to social science, from clinical expertise

to public health,” says Alan E. Greenberg, chair of

the Department of Epidemiology and Biostatics. Greenberg co-founded

the institute with Simon, director of the Division of Infectious

Diseases and vice chairman of the Department of Medicine.

“We are convinced that the institute as a group will

be stronger than each of us as individuals.”

Five institutions represent the pillars of the multidisciplinary

and synergistic institute—GW’s School of Public

Health and Health Services, GW’s School of Medicine

and Health Sciences, GW’s Columbian College of Arts

and Sciences, Children’s National Medical Center, and

the D.C. Veterans Affairs Medical Center. Affiliate memberships

have also been granted to faculty from Howard University,

Georgetown University, and the Washington Hospital Center.

Through the institute, faculty provide clinical care for

HIV/AIDS patients and their families, work with metropolitan

area health departments, collaborate with international and

national players in the policy arena, and conduct extensive

research. “With the institute, we now have a rapidly

responsive network with partnerships and relationships that

will lend themselves to new granting opportunities and affiliations

as well as value added for the University,” Greenberg

says. “We are acting locally yet thinking globally.”

Greenberg and Simon are quick to acknowledge Sylvia Silver,

professor of pathology and associate dean for health sciences,

as the impetus for forming the institute and a leading force

in articulating its vision. Silver is a well-funded and noted

researcher in HIV/AIDS and recently extended her work to South

Africa.

Professors Gary Simon, Sylvia Silver, and Alan E. Greenberg

are making an effort to expand the reach of education

and research projects addressing HIV/AIDS issues.

Jessica McConnell

|

|

As principal investigator in a collaborative effort to improve

the monitoring of the HIV/AIDS epidemic in Washington, D.C.,

Greenberg, along with epidemiology and biostatistics faculty

and staff members, is working with D.C.’s Department

of Health on epidemiological and surveillance issues, including

the District’s component of the Centers for Disease

Control and Prevention-funded National HIV Behavioral Surveillance

Project.

The institute has also developed a graduate certificate in

HIV/AIDS studies, which, pending final approval from the University,

will be offered through GW’s School of Public Health

and Health Services beginning in the fall of 2007.

“The GW HIV/AIDS Institute will have an important impact

city-wide,” says Lawrence D’Angelo, professor

of pediatrics and division chief for Adolescent and Young

Adult Medicine at Children’s National Medical Center.

“D.C. has declared HIV/AIDS a priority, and the institute

can provide the city with state-of-the-art research and collaboration.”

Fred Gordin, professor of medicine and chief of infectious

diseases at the D.C. Veterans Affairs Medical Center, stresses

that the recent creation of the GW HIV/AIDS Institute brings

together a network of experts and facilities not formally

linked in the past. “This is an opportunity for individuals

like me at the VA to be integrated more fully with all the

capabilities at GW,” he says.

A collaboration of this magnitude can positively impact

the HIV/AIDS research agenda. Gordin explains, “Advances

in the field have been remarkable in the last two decades.

The work that will be done because of the development of the

institute will not only help the field, but also help the

people right here in our own community.”

Clinical Studies

|

Postdoctoral student Luke Dannenberg conducts a ChIP-chip

experiment, which offers researchers the ability to

study the entire genetic information in a cell and determine

where a protein would bind on various chromosomes.

Jessica McConnell

|

“The test tube is the starting point, but until you

make that jump to patients, you never know how well it is

going to work,” says Simon, the institute’s co-chair.

At the GW Medical Faculty Associates, many HIV-infected individuals

seek antiretroviral agents and regimens. “We have established

a clinical practice in HIV/AIDS here that is well recognized

in the District and nationally,” he says.

More than 25 years after Simon diagnosed the first HIV/AIDS

patient, the fight against HIV/AIDS continues throughout the

District and the world. “The District of Columbia has

a major problem in both the diagnosis and treatment of HIV-infected

individuals,” Simon says. “The city is working

to improve this, but it is going to take a lot of work.”

A new approach was initiated by the MFA this year: a partnership

with Jeremy Brown, associate professor of emergency medicine,

to establish “Opt-Out Testing,” offering HIV tests

for all emergency room patients. “This is a new initiative

from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention to make

sure that we identify and subsequently treat as many infected

individuals as possible,” Simon says. “We believe

that up to one-third of HIV-infected people don’t know

they are infected and thus may not be receiving therapy. Since

they are contagious, they may unknowingly be infecting others.”

Examining High-Risk Behaviors

Understanding the motivations behind risky behaviors that

lead to contraction of HIV/AIDS is the stock in trade of a

research team led by the psychology department’s Senior

Research Scientist Carol A. Reisen and Professors of Psychology

Maria Cecilia Zea and Paul Poppen, chair of the department,

in GW’s Columbian College of Arts and Sciences.

In order to send the most efficient HIV prevention message,

GW’s Maria Cecilia Zea, Paul Poppen, and Carol

A. Reisen are trying to understand the reasons behind

risky behaviors.

Jessica McConnell

|

|

“We’re interested in prevention,” Zea explains.

“We are trying to understand the ‘whys’—the

root causes and reasons why people behave in risky ways.”

Zea adds that the underlying goal of the team’s research

is determining how to send the most effective message about

HIV prevention to the Latino community.

“We’ve learned that it’s really complex,”

Zea says about why the incidence of the disease has not continued

to decline. “It’s not as straightforward as receiving

information and changing behavior. There are a number of variables

contributing to risk—poverty, discrimination, geography.”

Poppen says the team’s research has dispelled an important

myth about behavior—that risky behavior is based on

individual personality differences. He explains, “What

we’ve seen is almost anyone may engage in some form

of risky behavior depending upon the context of the particular

sexual event itself—if you’ve had alcohol or drugs,

who your partner is, what the setting is, and so on. What

we’re studying is how the context associated with specific

episodes may make it more likely for anyone to engage in risky

behavior.

“The bigger point,” he adds, “is that information

is not enough. That’s part of the problem with health

issues that are behaviorally related. Behavior is not that

easy to control. It’s a big challenge.”

Adolescents and Young Adults

Cases of HIV infection continue to rise in adolescents and

young adults 12 to 24 years old, according to CDC officials.

Yet challenges in reaching HIV-infected youth still hamper

clinical research.

“When working with HIV-infected adolescents, adherence

to therapy takes on a completely new meaning, especially in

light of the fact that many of our patients are literally

managing their own health and well being,” D’Angelo

explains.

|

Shown above are reagents used in a ChIP-chip experiment

including vials of transcription factors and various

protein coding genes from HIV-1 genome.

Jessica McConnell

|

With the support of the National Institutes of Health and

the CDC, Children’s National Medical Center currently

is participating in two major research programs. The Pediatric

AIDS Clinical Trials Group led by Hans Spiegel, assistant

professor of pediatrics, microbiology and tropical medicine,

involves 26 sites in the United States and abroad and evaluates

pharmacokinetics, short-term safety, tolerability, and antiviral

activity of HIV medication in patients 6 to 17 years old.

D’Angelo leads the Adolescent Trials Network with 15

sites examining the care, prevention, and treatment aspects

of HIV in adolescents. The long-term goal of the program is

to develop viable community-based HIV prevention interventions.

Additionally, D’Angelo explores ways to limit secondary

transmission in HIV-infected adolescents. Identifying HIV-infected

adolescents presents its own set of challenges, as many of

these individuals are not aware of their HIV status. Children’s

National Medical Center has taken a lead role as a community

resource, offering counseling and testing services to adolescents

and young adults.

Forum Facilitates HIV Research Debate

The Forum for Collaborative HIV Research is an independent

public-private partnership established in 1997 to facilitate

discussion on emerging issues in HIV research. Housed in GW’s

School of Public Health and Health Services’ Department

of Prevention and Community Health, the forum brings together

experts from government, industry, academia, the patient community,

and foundations to address HIV prevention, treatment strategy,

health services, and policy.

Forum Executive Director Veronica Miller says the membership

profile ensures independence and neutrality, and is the key

to the forum’s uniqueness. “The forum identifies

barriers that keep the field of HIV research from moving forward

faster. At the same time, it builds communication and collaboration

between these various groups.”

The forum has benefited from the participation of a wide

range of GW researchers, including Zea; Greenberg; John Palen,

School of Public Health and Health Policy associate dean and

associate professor of health services; and Jeffrey Levi,

associate research professor of health policy.

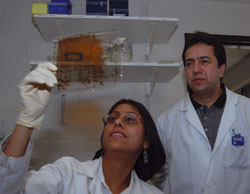

Graduate student Mala Ghai and Professor Fatah Kashanchi

view the result of an experiment that looks at the proteome

of an infected cell using 2-Dimensional gel electrophoresis

before a Mass Spec Proteomics analysis.

|

|

Zea participated in a forum workshop that examined racial

and ethnic minority issues in the management of HIV care,

prevention, and research. She explored whether Latino gay

men disclose that they are HIV-positive to their social network.

Greenberg participated in a workshop to study biomedical

interventions to HIV infection. Instead of the traditional

approach to educating people about how their sexual behavior

can lead to HIV infection, this workshop investigated methods

such as using topical compounds called microbicides to protect

against sexually transmitted infections, providing antiretroviral

treatments to people at high risk to HIV exposure, circumcising

men, and treating herpes simplex virus type 2 (HSV2) since

HSV2-positive men showed a consistent two-fold increase in

the risk of HIV acquisition.

Additional forum projects range from assessing the current

state of HIV therapeutic vaccine development and potential

barriers for moving vaccines forward, especially through the

regulatory process, to designing clinical trials of treatments

and interventions for lipodystrophy—body fat redistribution

that causes side effects that may threaten the long-term success

of antiretroviral therapy.

Systems Approach to Studying HIV/AIDS

Fatah Kashanchi’s research explores the entire HIV

infection system, including the virus, the cells it infects,

and the methods involved in the infection and replication

processes. Through the use of bioinformatics—the collection,

classification, storage, and analysis of biological information

using computers—Kashanchi, professor of biochemistry

and molecular biology, deciphered the complex code of HIV-1,

the virus that causes AIDS. Kashanchi’s research continues

to rely on bioinformatics to study HIV using two technologies:

genomics and proteomics.

“I want to know how certain proteins and pathways

involved in HIV infection talk to each other,” Kashanchi

says. “The only way to study this is to use the systems

biology approach of both proteomics and genomics.”

To study the genomics of HIV-infected cells, or all of the

nucleotide sequences in the chromosomes, Kashanchi routinely

searches through tens of thousands of gene arrays for alterations

in pathways, including transcription, translation, and cell

death. Using this information as well as various bioinformatics

tools, he recently designed inhibitor drugs that seek and

destroy HIV-infected cells.

|

Reagents used to perform molecular biology experiments

related to HIV-1 genomics and proteomics research.

Jessica McConnell

|

To study the proteomics of HIV-infected cells—the structure,

function, and interactions of the proteins produced by the

genes—Kashanchi inspects amino acid chains for changes

to viral proteins following infection with HIV. This approach

could ultimately lead to an AIDS vaccine.

“Genomics and proteomics allow us to study the effects

of specific inhibitors and peptides that could be used as

drugs against HIV,” Kashanchi says.

To learn how the human immune system responds to HIV, Kashanchi

recently developed the first small animal model for HIV/AIDS

that utilizes human stem cells to repopulate the animal with

human immune cells. With this model, he will trace the steps

of an HIV virus as it enters and infects an immune cell. With

this route mapped out, Kashanchi can test different peptides

and drugs to see if they inhibit entry of HIV into an immune

cell.

HIV Infection and Increased Risk of Heart Attack

HIV infection is often associated with an increased risk

of developing atherosclerosis—a build up of fatty deposits

in the vessels feeding the heart. Deposits slowly narrow the

coronary arteries, and complete blockage leads to heart attacks.

Researchers previously attributed these increased risks in

HIV patients to antiretroviral therapy. However, new research

conducted by Michael Bukrinsky, professor and vice chair of

the Department of Microbiology and Tropical Medicine, and

graduate students Zahedi Mujawar and Matthew Morrow shows

that this increased risk may be due to HIV infection itself,

a side effect of HIV’s strategy to increase its infectivity.

“HIV prevents infected cells from releasing cholesterol

into the plasma,” Bukrinsky says. “This makes

the virus happy, because it needs cholesterol to make new

virus particles capable of infecting other cells.”

Bukrinsky currently is investigating what happens when HIV-infected

cells are treated with drugs that stimulate cholesterol release

from cells. “The cells still make the virus, but the

virus is practically noninfectious, because it cannot get

necessary cholesterol,” he says.

In another avenue of research, Bukrinsky examines small molecule

compounds called oxadiazols that inhibit HIV. These novel

antiviral agents come at the perfect time—when incidences

of drug toxicity and resistance are increasing during long-term

treatment of HIV-infected patients. Because HIV can replicate

in non-dividing cells, blocking cell division is not enough

to stop HIV infectivity. Instead, HIV must be blocked from

entering the cell nucleus. The oxadiazols Bukrinsky discovered

inhibit viral DNA from entering the nucleus and can be used

in addition to the HIV cocktail, a three-drug combination

regimen, to boost its effectiveness.

“We participated in the design and testing of these

compounds,” Bukrinsky says. “Currently, studies

are focusing on the pharmacokinetics of these compounds to

improve their delivery. We hope that clinical trials will

be initiated soon.”

For more information about the GW HIV/AIDS Institute,

visit www.gwumc.edu/sphhs/institutescenters/gwuhivaids.

Abby Vogel is a research writer in the Medical Center

Communications and Marketing Office.

Linda Dent, Sarah Freeman, Debbie Goldstein, and Thomas

Kohout contributed to this article.

|