|

GW’s landscape design program director tells us how.

Given high demand for and dwindling supply of many of Earth’s natural resources, we increasingly are hearing about ways to protect our precious commodities. Eco-friendly words of the day include “organic,” “natural,” “going green,” and a new take on The Three R’s: “reduce, reuse, and recycle.”

We try to help our beleaguered ecosystem. We recycle our waste, insulate our homes, use gas-efficient vehicles, and buy energy-efficient products. What more can individuals do to help? The answer is outside your own front door: Sustainable landscapes.

Sustainable landscape design is one of the newest soldiers in our ecological army. Sustainable landscapes employ best management practices for conservation of natural resources, while satisfying current needs and not jeopardizing the needs of tomorrow’s generations.

Sustainable landscapes use water, energy, soil, and native flora and fauna as efficiently as possible to restore the ecological balance. Sustainable landscapes help the environment on a grand scale—across cityscapes at factories, shopping centers, and other large developments—and on the small scale—at individual homes.

A rain garden, also called a bioretention area, provides a homeowner with a way to retain storm water. Rain gardens typically are created in a depressed area of a yard where rainwater from gutters and higher ground collects. To make a rain garden, a homeowner digs out the area and fills the bottom with a porous mixture of gravel and soil, then creates a planting bed on top with plants that thrive on moisture. The plants take in some of the retained water and the rest is absorbed within hours into the aquifer.

Courtesy of www.raingardens.org and www.wmeac.org“Sustainable landscape design is not just a buzzword but is symptomatic of issues facing us everywhere,” explains assistant professor Adele Ashkar, director of GW’s landscape design programs in the College of Professional Studies. “For example, we are drawing down our ground water supply at an alarming rate. We have more people and a greater use of water. Instead of replenishing our aquifers, we are sending our used water back into the sea. We need to find ways—one yard at a time—to teach everyone to keep the storm water in the ground.

“People might assume that one homeowner will not make a difference and that it is large landscaped areas that need to exercise more stringent conservation. While this is important, single-family houses cover more land than any other use. If we can get more homeowners to be more conservation minded, the better it will be.”

Embracing the growing importance of sustainability, GW in August 2007 launched a Sustainable Landscape Design program that teaches the best practices in landscape conservation and sustainability adapted to the small-scale landscape (see Mastering the Sustainable Landscape sidebar). To promote the topic of sustainability, Ashkar participated in GW’s Classes Without Quizzes program during Alumni Reunion Weekend this past fall. Her presentation, “Saving the Bay, One Yard at a Time: The Importance of Sustainable Practices in Residential Property,” illustrated many ways individual homeowners can help the environment.

Ashkar is a landscape architect who earned her Bachelor of Fine Arts from Rhode Island School of Design and her Master of Landscape Architecture from Harvard University Graduate School of Design. Her interest in landscape design traces back to her high school year when her mother introduced her to a friend who was a landscape architect. Ashkar learned how the profession could combine her interests in science and art. She joined GW 10 years ago as director for the Landscape Design program.

“Sustainable landscape design is very important to individual homeowners because we are doing many things in everyday practice to damage our environment without even realizing it,” Ashkar says. “Our lawns leech fertilizers and toxins into the ground and waters. Our gutters and drainage systems pipe all the water we use out of our area, rather than using it to restore the ground water. Our energy costs are skyrocketing, yet we cut down trees rather than use them to provide insulation in the summer and allow sunshine in during winter. We can provide solutions to so much of that by using sustainable practices in our homes and gardens.”

These practices involve simple changes. The rewards include reduced water and energy costs, pollution prevention, wildlife benefits, and less workload in the yard.

Water Washing Away

Perhaps the most important sustainable landscape practice involves water. Amid recent headlines about water shortages across America, an Associated Press story this past October reported, “The U.S. government projects at least 36 states will face water shortages within five years because of a combination

of rising temperatures, drought, population growth, urban sprawl, waste, and excess.”

But as Ashkar explains, the issue is more complex than just a shortage of water. She illustrates her point by explaining how we currently dispose of storm water.

“If you follow a drop of rain as it hits our homes, where does it go? In the Chesapeake Bay area, rainwater travels from our homes, along impervious surfaces such as driveways and roads, ends up in the Potomac River or other tributaries, then runs into the Chesapeake,” Ashkar says.

“Along the way, the load of water increases, generating more and more velocity and resulting in erosion. Also entering the water are soil particles, debris, and pollutants such as oil or lawn chemicals. All this enters our waterways, adding to the damage.

“A sustainable landscape approach would prevent these downstream issues by capturing the water on site, using it in our gardens, and allowing it to infiltrate back into the ground and reinfuse our aquifers.”

Ashkar mentions two ways to accomplish this change. The first harkens back to the pioneer days when people captured rainwater in cisterns for later use. Yes, the rain barrel is making a comeback, but in an improved fashion.

These rain barrels typically are made of high-impact plastic and come in many capacities, with the larger ones exceeding 80 gallons. They attach to a downspout and collect rainwater for later use in the garden. Should the rain barrel overflow during a storm, most designs have an overflow hose that the homeowner can situate to direct the water away or use when watering lawns and gardens.

If you worry about mosquitoes laying eggs in the water, that’s preventable. Most barrels have very fine screening on top to prevent mosquito entry. Also readily available are nontoxic products that kill mosquito larvae but do not harm the garden.

Another way to retain water is to create a rain garden, which also is known as a bioretention area. This usually is created in a depressed area in a yard where rainwater from gutters and higher ground is directed.

“The depressed area is dug out and its bottom is filled with a porous mixture of gravel and soil, then a planting bed is created at the surface and filled with plants that enjoy having wet feet,” Ashkar explains. “The retained water waters the plants, then any excess is absorbed within hours into the aquifer.

“To determine the size of the rain garden, we carefully calculate the square footage of the home and yard’s impervious surfaces, then determine the amount of water received during a typical storm. The rain garden is designed to accommodate all the rainwater expected to drain into it.”

Another good spot for a bioretention area is near or within large expanses of impervious surfaces, such as a large patio or a parking lot.

“Parking lots are often just open deserts of hot asphalt. Rainwater cannot penetrate these impervious surfaces, so it is piped away, picking up debris and pollutants as it runs off. If you create small depressed islands of ground and plant them with low-maintenance, water-loving plants, these capture the storm water, help restore the aquifer below, and mitigate runoff problems,” Ashkar explains.

Energy Savings

Another fundamental sustainability issue is energy efficiency. When designing a landscape or a garden, Ashkar advises homeowners to think of energy losses and gains, then use that information to place the landscaping.

“It starts with building houses with the proper cardinal orientation for the best energy-efficient exposure. All too often our houses have the wrong exposure. A house facing north or south will have a very cold side and a very hot side, but a house facing east or west gives the landscape designer a better means to take advantage of the exposure,” she says.

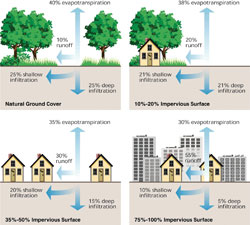

How Much Runoff?

Relationship between impervious cover and surface runoff. Impervious cover in a watershed results in increased surface runoff. As little as 10 percent impervious cover in a watershed can result in stream degradation.

Source: “Stream Corridor Restoration: Principles, Processes, and Practices,” (10/98).

By the Federal Interagency Stream Restoration Working Group.

“For example, the landscape designer can plant deciduous trees on the east and west exposures to shade the house from sunshine in the summer, yet the trees lose their leaves and expose the house to sunshine in the winter. This is most advantageous on a home’s west side, allowing the homeowner to exploit the low angles of winter sun to warm the windows.

“Another energy-efficient concept is to consider the prevailing winds. By placing a nice evergreen barrier where prevailing winds come to a site, you are in a sense using plant materials as insulation,” she adds.

One energy-saving technique generating a lot of discussion is the vegetative roof, commonly called the “green roof.” One of the best-known and largest of these is the 10-acre green roof atop the Ford Motor Co.’s Dearborn, Mich., factory.

“Rather than use asphalt shingles, the green roof has a waterproofing layer topped with a very thin layer of growth medium, which is planted with a very hardy low-growing plant, such as sedums,” Ashkar says. “Green roofs are beneficial because they absorb the rainfall, while also insulating the roof and delivering great energy savings.”

Going Native

A third component of sustainable landscape aims to minimize the use of extra irrigation, fertilizers, and pesticides. Using native plants is one answer, Ashkar says.

“Although we all like our Japanese Maples, it is an exotic introduction and not necessarily suited to our gardens. In any given area, native plants are the most adapted to that climate,” she explains.

“While we often think of native plants as weeds and fear they will be unattractive in our gardens, this is not the case. With a combination of well-selected plants and proper design, we can have beautiful gardens with native plants.

“But don’t go poaching in area woods to get plants for your garden. Native plants are increasingly available in local nurseries; find a local nursery that is properly propagating the native plants,” she states.

The concept of bioretention was first conceptualized in Maryland by planners in Prince George’s County who were looking for ways to manage storm water. Parking lots and other paved surfaces are great places for bioretention areas because of their large amounts of impervious surfaces. This rain garden is installed in Olney, Md., at Fletcher’s Service Center, which also draws upon solar energy to help power its pumps.

Photos by Jessica McConnell

Photos by Jessica McConnellAshkar points to many advantages of native plants. They reduce the need for irrigation, fertilizers, herbicides, and pesticides because they have evolved to survive in their native environment. Less maintenance is thus involved. They also will attract native fauna—such as beneficial insects, birds, and other wildlife. This kind of garden establishes a native ecosystem with the food chains appropriate for the area.

On the other hand, introducing non-native plants usually requires more maintenance to assure they thrive, but sometimes something worse occurs. The non-native plant thrives to the point of becoming out of control and invasive, destroying native plants. This is the case with Kudzu, an Oriental vine introduced to the United States years ago; millions of dollars now are spent to kill this rampantly growing vine in nearly all southern states. Removal of invasive non-native plants and restoration of natural environments also is a component of sustainable landscapes.

Using native plants can translate into beautiful yards, Ashkar adds. You can practice sustainability and win Garden of the Month, too.

“Consider a sustainable garden in Arizona. You are not necessarily stuck with having only a cactus garden. Parts of it could have native cacti and desert plants, but the yard’s more moist areas could have plants native to Arizona’s creeks and valleys,” she explains.

If you really long for a New England garden, lush with plants, install just a patch here and there. Then take care of it as naturally as you can, Ashkar advises.

In promoting sustainable landscapes, designers are combining the traditional aesthetic and organizational lessons of landscape design with functional and energy-conscious aspects of creative thinking.

“We truly do need to reduce, reuse, and recycle,” Ashkar says. “What really appeals to me about sustainable landscape design is that we’re not saying we have to do without, but we need to think in smarter ways and use what we have conservatively and creatively.”

Mastering The Sustainable Landscape

A rain barrel attaches to a downspout and collects rainwater for later use in the garden. Most designs

have an overflow hose that the homeowner can situate to direct the water away during a storm or to use when watering lawns and gardens. Most barrels have very fine screening on top to prevent mosquito entry.

A. English

If you want a career in landscape design, GW offers a flexible path within the College of Professional Studies.

GW has catered to the need for landscape design professionals since 1973. Originally offered as a non-credit, continuing education program, Landscape Design joined the College of Professional Studies in 2003 to become an 18-course/28-credit graduate certificate program. Recognizing the rising need to protect our environment, this past August GW launched a seven-course/15-credit graduate certificate in sustainable landscape design.

“The concept of landscape sustainability is what is moving the thinkers in this profession right now,” says Adele Ashkar, assistant professor and program director. “The global issues are so great that homeowners all over are going to be wanting design services that address sustainable issues. We intend to train the designers to be able to do that.”

Students can earn a graduate certificate in either program or a Master of Professional Studies in Landscape Design. The master’s degree is earned by combining the 28-credit Landscape Design program with the 15-credit Sustainable Landscape program. (GW refers to this type of degree as “stackable credentials.” See www.ocp.gwu.edu/sl.)

“Our typical students are career changers—highly educated and successful—all kinds of people who are ready for a change. They usually have had an earlier experience with gardens or design and wish to go back to that,” Ashkar explains.

Flexible class schedules are a hallmark of the program. Students typically take the first course, “Introduction to Sustainable Design,” in the summer, then they can take as long as five years to complete the program. Some courses are held on weekends, in all-day intensive formats, and some have online credit units. There also are four distance learning courses.

Besides the introductory course, the six remaining courses teach: ecological restoration, tools for sustainable design, the green scale spectrum, sustainable design methods, sustenance and the landscape, and sustainable design charrette.

Classes are offered at GW’s K Street Center in D.C. as well in Virginia at the Alexandria Graduate Education Center and at the GW Virginia Campus in Ashburn. |

Greening GW

The University’s attention to sustainability was enhanced this past fall when GW President Steven Knapp formed the Task Force on Sustainability. This group will spend the academic year evaluating the University’s operations and academic programs in the areas of environmental stewardship and climate change, as well as examining and recommending improvements in relevant University policies.

Led by professor Mark Starik, chairman of the Department of Strategic Management and Public Policy in the School of Business, and Lew Rumford, senior adviser for business development, the task force will issue a report this June that addresses energy conservation, resource and waste management, sustainability awareness, research programs, learning/curricular opportunities, procurement policies, and service initiatives and partnerships. The task force, comprising 12 students, faculty members, and staff members (as well as Diane Robinson Knapp), went immediately to work, soliciting suggestions from the GW community and exploring best practices employed by other universities.

The group’s efforts complement GW’s other green initiatives. GW is incorporating sustainability concepts in its upcoming Foggy Bottom Campus development. Knapp is the first university president in D.C. to sign the American College and University Presidents Climate Commitment, which reinforces

the responsibility that higher education institutions have in developing global warming solutions. Students also participate in student-led environmental organizations, such as Green GW and GW Net Impact, and GW’s Class of 2007 created the Campus Green Fund, which supports projects to make the University more environmentally friendly and energy efficient. One such project is the Foggy Bottom Campus’ first-ever green roof, which will be installed this summer atop a portion of the 1957 E Street building at the City View Room Terrace

|

|