GW Law and India: An Expanding Relationship

From New Delhi to Bangalore, GW Law is building bridges of understanding between the United States and Indian legal communities through its fast-growing India Project, a collaborative enterprise fostering broad-based relationships and heightened international dialogue on issues of mutual concern.

Established in 2003, the path-breaking partnership has carved out a unique niche in the intellectual property law world through its well-attended conferences, programs, and events across India. “The project was the brainchild of GW IP Law alumnus Raj Davé, LLM ’03, a graduate of the Indian Institute of Technology-Kharagpur, who approached us about joining forces to help strengthen India’s intellectual property law capacity,” says Susan Karamanian, associate dean for international and comparative legal studies at GW. The Law School’s prominence in intellectual property law, coupled with the recent boom in India’s technology and financial sectors, set the stage for a winning partnership.

Half a decade later, the India Project is thriving, highlighted by an annual IP mock trial involving both U.S. and Indian lawyers and judges, and an annual IP rights summit, co-sponsored by the Confederation of Indian Industry. The highly-regarded events, which are open to the public, attract lawyers, judges, business leaders, government officials, and scholars from around the world. Many distinguished Indians—including members of Parliament, Supreme Court justices, and the former president of the Indian Bar Council—support the project as panelists and participants in GW-sponsored legal roundtables, and counsel and judges in the annual mock trials, Karamanian says. “We also benefit from the participation of outstanding lawyers and judges from around the globe, such as Judge Randall R. Rader, JD ’78, of the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit, who has been an important member of our team since the beginning of the India Project,” she states.

Susan L. Karamanian

GW-sponsored delegations of prominent judges, legal scholars, and industry leaders from the United States, Europe, and Asia visit India annually to meet with high-level Indian counterparts and discuss issues relating to comparative intellectual property law. “We’ve developed ties with some of the leading thinkers and major institutions in the country,” Karamanian says. “What really distinguishes our work is that it is a collaborative endeavor, not a one-way street.”

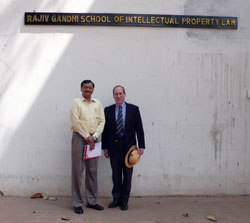

An exciting byproduct of the India Project is GW Law’s relationship with the prestigious Indian Institute of Technology in Kharagpur—India’s leading technology university. The Law School signed an agreement in 2006 to help the IIT-Kharagpur develop the new Rajiv Gandhi School of Intellectual Property Law—the first intellectual property law school in India. “We helped design the curriculum and train some of the faculty members, and hope to implement student and faculty exchanges in the future,” says GW Law School Dean Frederick M. Lawrence, who visited the Rajiv Gandhi School earlier this year. “The Rajiv Gandhi School will play a very significant role in supplying lawyers to the intellectual property bar of India, but, more than that, it will open many avenues of legal scholarship to the extraordinarily bright young men and women who are studying there.”

The Law School is now poised to take its relationship with India to the next level as it works on establishing an India Studies Center on GW’s campus. Gauri Rasgotra, a former partner at the leading Indian law firm Khaitan & Co., was hired by GW Law to spearhead the endeavor. The center, focusing on comparative law between the United States and India, will explore a wide range of issues relevant to U.S.-India legal relations beyond IP. “We are working to shape and expand programs relating to the complex legal challenges, both international and domestic, that face India,” Rasgotra says.

Dean Frederick M. Lawrence visits with Professor S. Tripathy, director of the new Rajiv Gandhi School of Intellectual Property Law at the Indian Institute of Technology, Kharagpur.

Susan L. Karamanian

Topping the list is a major corporate law project in tandem with the Indian Ministry of Corporate Affairs. “We have a very strong relationship with the ministry and are working closely with it in connection with the new Indian Institute of Corporate Affairs in New Delhi, funded by the government of India,” Karamanian says. The institute, which was two years in the making, is a think tank for policy making and research on Indian corporate law, as well as comparative corporate law—incorporating best practices from the United States, Europe, and Asia. It will also have a strong training component. GW Law will work with the IICA on a broad range of issues relating to corporate law. “This collaborative endeavor is an ideal project for our Law School, since it requires substantial expertise across a wide range of corporate law disciplines, together with a clear recognition of the benefits of a strong corporate law system to the economy of India,” Karamanian states.

November witnessed the official groundbreaking of the institute. A formal signing ceremony between the IICA and GW Law is scheduled for the end of February, when the Law School sends its next delegation to India. “We’re pleased to be a part of this new collaborative effort,” says Lawrence, who plans to travel to New Delhi for the ceremony. “Indian corporate law lags far behind the country’s corporate culture, and we look forward to working with the IICA to reexamine Indian corporate law and help bring it up to the 21st century.”

The relationship is enhanced by the IICA’s recent agreement with the Rajiv Gandhi School of Intellectual Property Law to work together on common issues. “That really closes the circle,” he states. “It’s exciting to be part of this collaboration between two young and important institutions in India.”

Dean Frederick M. Lawrence and Associate Dean Susan L. Karamanian meet with members of India’s Ministry of Corporate Affairs, including the ministry’s Secretary Anurag Goel (fifth from left).

Susan L. Karamanian

In another development on the corporate law front, GW Law is putting the final pieces in place for a mock trial in India this February involving corporate insolvency issues. “It’s pretty timely right now given worldwide economic hardships,” Karamanian states. “Our goal is to emulate the model that we use for our IP mock trials—we’ll draft an issue and have U.S. lawyers present the case before a U.S. judge and jury under U.S. law, with the same issue being argued later in the day by Indian lawyers before an Indian judge under Indian law.” The session will culminate in a comparative discussion on the differences between the two legal systems.

GW Law is furthering its network of U.S.-Indian relationships by reaching out to additional Indian institutions, Karamanian says. “Just recently, the vice chancellor of the Aligarh Muslim University, one of the most distinguished universities in India, visited us in Washington to discuss collaborative ideas, such as hosting a videoconference forum on Islamic finance,” she states. “In light of the size and importance of India’s Muslim community, we believe that a relationship with institutions representative of that community is beneficial in many respects, particularly given the need for dialogue.” Lawrence and Karamanian will be visiting AMU on their upcoming February trip.

As the GW-India partnership grows, the Law School is witnessing a substantial increase in the number of LLM students from India. “We are delighted that we are now attracting some of India’s finest law students to GW, which has added enrichment to the GW Law community,” Karamanian says.

India’s former Deputy Chief of Mission Ambassador Raminder Singh Jassal confers with Associate Dean Susan L. Karamanian and GW Elliott School of International Affairs Professor Karl Inderfurth, the former U.S. assistant secretary of state for South Asian Affairs, following the 2007 roundtable at the Embassy of India.

Susan L. Karamanian

The India Project also enhances GW life through a variety of Washington-based events, such as talks by prominent Indian legal scholars. “This fall, we brought the former Law Minister of India Ram Jethmalani to the Law School to speak about the U.S.-India civil nuclear agreement,” Lawrence says. “He is a remarkable figure in Indian law, who spoke to a packed room of students, faculty, and alumni.” Other recent highlights include a roundtable last year at the Embassy of India on the U.S.-India Civil Nuclear Agreement, co-hosted by GW Law and the Washington Foreign Law Society, and a well-received talk at the Law School in 2006 by Kapil Sibal, Indian minister for science and technology. The Law School is currently working on convening a major conference in Washington this spring focusing on U.S.-Indian constitutional rights and legal systems.

Turning his attention to the future, Lawrence says that the sky is the limit when it comes to areas of law that are ripe for collaboration. “Government procurement law, environmental law, constitutional law, international and comparative law, and administrative law are all great strengths of our law school, and we hope to build on these strengths by developing comparative projects in those areas through our India Studies Center,” he states.

Government procurement law is one of the leading fields on the project’s radar, Karamanian affirms. “GW is the only law school in the United States offering a degree in government procurement law and, indeed, founded the discipline in the U.S.,” she says. “India has a large civil service, and its procurement process is quite complicated and under regular scrutiny, which makes this an ideal area for expansion.”

Environmental law also holds tremendous potential for collaborative work. “The Indian judiciary has been active in enforcing environmental laws,” Karamanian states. “In fact, the Indian Constitution includes a directive principle calling on the State to protect and improve the environment. This leads into another area of inquiry, constitutional law. Certainly the United States and India, which share the common law tradition, as well as democratic principles and strong constitutions, must have a considerable amount to learn from one another on a variety of constitutional issues.”

Associate Dean Susan L. Karamanian (third from left) and GW Law Professor Martin Adelman (second from right) spend time with former GW Law Visiting Professor Shamnad Basheer (far left) and GW Law alumni during the IPR Summit in Mumbai in 2007.

Susan L. Karamanian

Lawrence says that the India Study Center plans to build on its well-established IP law base by moving “carefully, deliberately, and building relationships as we go.” He explains: “Our goals throughout have been to work consistently and methodically on discrete projects in areas of law where we have a comparative advantage, really ground them, and then build on them in a strategic way. We’ve received great enthusiasm in India for our work to date and it is my hope that we expand our success to a growing number of fields.”

He praises the efforts of Rasgotra, who came to GW Law to take over the reins of its India-related activities following her husband’s posting to the Indian embassy in Washington. “Gauri has been a great addition to our team, who has brought great energy and vision to the job,” Lawrence says.

The dean also applauds the support of Vinod Gupta, who made a recent gift of $500,000 to the Law School for India programming. “He is a very important friend of the GW Law family, who played a leading role in the founding of the IP law school at Kharagpur and is extremely enthusiastic about efforts for greater collaborations between American universities and Indian universities,” Lawrence states.

Rasgotra says that GW Law’s increasing engagement with India parallels the growing richness and depth of India-U.S. relations in general. “GW’s India Project was the earliest recognition of India’s rapid emergence on the world stage by a law school in the United States,” she says. “The growing scope and range of contacts the center has established with a diverse group of academic and corporate institutions in India is eloquent testimony to the center’s impact.”

Susan L. Karamanian

Karamanian says that it’s a privilege to be part of the expanding relationship. “We are making substantial contributions to the discussion of a wide range of important issues facing the international community,” she states. “We offer a forum and we also have a message, which is that the careful and critical review of issues of mutual concern will lead to better laws and policy. My colleagues and I take a great deal of pride in the fact that The George Washington University Law School is playing this role.”

“I think the potential for joint work going forward is almost limitless,” Lawrence concludes. “The United States and India are the world’s two largest democracies, joined by a common language, as well as a commitment to the rule of law, democratic institutions, and capital markets. At the same time, there are also enormous, exciting differences between the two countries that make the opportunity for comparative work extraordinary. Aiming high, there’s no reason why GW Law School should not become the focal point for comparative American-Indian law studies in the United States.”