Head Case

Using new cranial measurement methods, GW researchers uncover the possible ancestry of the hobbit.

By Jaime Ciavarra

|

The hobbit skull compared with the skull of a modern day Homo sapien. Scientists say Homo floresiensis had a brain the size of a grapefruit.

Peter Brown

|

Roaming among Komodo dragons and pygmy elephants, miniature humans with grapefruit-sized brains and 3-foot-tall stature inhabited the Indonesian island of Flores as recently as 12,000 years ago. Since the discovery of their skeletal remains in 2003, scientists have argued about how these hobbit-like hominids should be classified.

GW researchers, using innovative cranial measurement methods, have delved head-first into the debate.

In a study published in March in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, paleoanthropologists Adam Gordon, Lisa Nevell, and Bernard Wood present new evidence that shows the tiny humans, dubbed “hobbits” because of their small stature, should be classified as their own species, Homo floresiensis. Their ancestry, the researchers say, may trace back to ancient Homo species in Africa, showing that human evolution didn’t follow a linear path. Splitting from our own lineage as much as 1.7 million years ago, the hobbits may have lived up until the time when modern humans began peopling the Americas, they say.

“Our work argues that this is a very different species, and yet it persisted alongside modern humans on the same planet for close to 2 million years,” says Dr. Gordon, postdoctoral research fellow with GW’s Center for the Advanced Study of Hominid Paleobiology. “That’s kind of cool.”

The hobbits have been a source of controversy in the scientific community since Australian and Indonesian researchers unearthed the bones, including one skull, in a Flores cave five years ago. The discovery of the tiny humans, who grew no larger than a 3-year-old child, has been described as one of the most sensational recent findings in paleoanthropology. Some researchers argue that the hominids were Homo sapiens who evolved to their small stature because of environmental conditions or were shrunken by a disease. Others contend that the hobbits were so unusual—and so distinct from modern humans—that they should be classified as a species of their own.

In an attempt to clarify the debate, Dr. Gordon, Nevell, and Dr. Wood studied the size and shape of the only skull found in the remains. Named LB1 because it was removed from the Liang Bua cave in Flores, the cranium indicates the hobbit (determined by scientists to be a fully grown adult female) had a brain about one-third the size of modern adult humans. Focusing on the external part of the skull, the team performed two sets of analyses to compare the 18,000-year-old LB1 with skulls of other hominids.

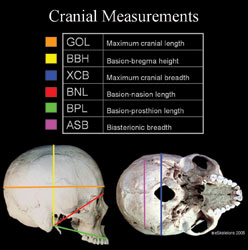

For the first study, Dr. Gordon, Nevell, and Dr. Wood gathered published cranial measurement data on 2,524 modern humans, 30 ancient hominids of various species, and the hobbit. The team chose measurements designed to determine the overall shape of the skull, such as the width, length, and height of the brain, the degree of expansion of the back of the skull, the projection of the lower face, and the length of the cranial base. Through statistical analysis, the team found that LB1 most resembled skulls from the species Homo erectus in east Africa and the Republic of Georgia, dating back some 1.7 million years.

GW researchers used six cranial measurements to analyze the hobbit skull, including the width, length, and height of the brain, the degree of expansion of the back of the skull, the jut of the jaw, and the length of the cranial base. Here the measurements are shown on a modern human skull.

Lisa Nevell, Adam Gordon, and www.eskeletons.org

|

|

Next, the researchers considered the effects of scale, or how shape changes with size, to determine what a modern human skull would look like if scaled down to the size of the hobbit skull. They found, through this innovative new method of “shrinking,” that the two skulls didn’t resemble one another at all. When they scaled down other hominid skulls, however, the hobbit most resembled Homo habilis, the most primitive and small-brained species of our genus, which also lived in Africa some 1.7 million years ago.

“What we were getting was a picture of very young material looking like material from 1.7 to 1.8 million years ago,” Dr. Gordon says. “So it’s arguing that we’ve got this lineage of hominids that breaks off from our own, maybe as long ago as 1.8 million years, but it persisted until the time when modern humans started peopling the Americas.”

Critics who believe that the hobbits may be diseased Homo sapiens argue that the team’s study does not take into consideration the genetic disorder microcephaly, which causes a small head.

The team members had gathered some measurements of skulls with microcephaly, but they did not have all six measurements used in the cranial study. Without the complete evidence, they decided to forgo directly addressing the pathology issue, Dr. Gordon says. Nevell, co-lead author and a graduate student in the GW hominid paleobiology program, also notes that the cranial shapes of LB1 and Homo erectus differed from scaled modern human skulls in the same way.

“We are not aware of any inherited genetic condition that would cause modern human crania to so closely resemble the shape of Homo erectus,” Nevell explains.

Paleoanthropologist Peter Brown, co-author of the study describing the hobbit discovery, says the team’s work is consistent with other scientific findings.

“The important research of Dr. Gordon, Nevell, and Dr. Wood makes a substantial contribution to an increasing body of evidence supporting an early departure of our hominin relatives from Africa,” says Dr. Brown, chair of paleoanthropology at the University of New England in New South Wales, Australia. “Along with recently completed research on the anatomy and function of the wrist, foot, shoulder, and limb proportions, it appears that our relatives walked out of Africa 2 million years ago, or perhaps considerably earlier.”

The discovery, and the quest to learn more about these unusual humans, underscores the ever-challenging role of science in explaining our history on Earth, says Dr. Wood, a University professor and director of GW’s hominid paleobiology doctoral program.

“The thought that these creatures co-existed in time…with modern humans,” Dr. Wood says, “emphasizes the extent to which evolution can still hold surprises for us.”

|