Two Wheels on a Mission

More than a thousand students came to campus for the Clinton Global Initiative University with ideas to improve the world. Among them was a GW trio with a bicycle that they hope will save lives.

Backstage at Lisner Auditorium, waiting to see if voters across the country had chosen his group's project as the most compelling in a crop of socially progressive innovations by college students, senior engineering student Matt Wilkins was struck by how surreal his weekend had become.

"We were just hanging out talking to [comedian and Daily Show host] Jon Stewart for 20 minutes," he recalls, still slightly amazed. "I gave him my business card. He showed us pictures of his kids."

It was one in a series of surreal moments that weekend for Mr. Wilkins and his partners, business student Chris Deschenes and engineering master's candidate Jon Torrey. The three were participants in the fifth annual Clinton Global Initiative University (CGI U), a weekend-long event hosted by GW in March that brought together more than 1,000 students from 300 universities, all 50 states, and 82 countries to discuss solutions to pressing global issues, attend sessions with celebrities and experts in the world of social entrepreneurship, and take part in a massive service project.

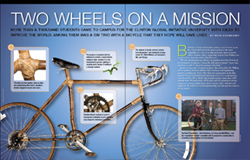

The joints are held together using an adhesive-soaked hemp fiber that is omnidirectionally wrapped to secure each piece.

The bamboo is locally sourced, coming from teammates' own backyards in Long Island, N.Y. (Matt Wilkins), and Annapolis, Md. (Jon Torrey).

In order to participate, students had to propose a "Commitment to Action"—a practical, concrete solution to a social problem. For Mr. Deschenes, Mr. Torrey, and Mr. Wilkins, that solution had two wheels and a frame made of one of the world's most common plants.

An avid cycler as well as an engineer, Mr. Wilkins has long been interested in building his own bikes. "I started thinking of different building materials to use. Steel is boring; aluminum is too hard; titanium is too expensive," he says. "So I went to Google and saw that people make bikes out of bamboo. It immediately clicked in my head: I have bamboo in my backyard. I can cut this down, and it'll cost me nothing."

He enlisted Mr. Torrey, a friend from the engineering school, to help him with the project. "Bamboo's been used to build bikes—to build anything, [including] structures and scaffolding—for a long time," Mr. Torrey explains. "If you take bamboo and you heat- and pressure-treat it, the cellulose cells collapse and form really strong bonds. It's as strong as a metal."

Not only that, Mr. Wilkins adds, but it's also a luxury material. "Carbon fiber is the top-grade material for bike frames—the most expensive, the lightest—and what's best about it is its shock absorbency, so if you ride over bumps it feels like you're sitting on a cloud. But treated bamboo is actually four times more shock absorbent than carbon fiber." It's also lighter than aluminum and, of course, exponentially cheaper than either.

It was Mr. Deschenes, then studying in London, who found out that GW would be hosting CGI U and saw the potential for his friends' project to become something more than a hobby.

Standard bicycle hardware is used to leverage the availability of parts and allow easy swaps for customized assemblies.

The bamboo is varnished with the adhesive to provide a sealed exterior, making it water resistant. It is also heat treated to prevent splitting or cracking and to temper it, leading to a stronger material.

Biking is a simple, green solution to problems like urban congestion, as well as an affordable means of transportation for people in underdeveloped countries. The trio could build bamboo bikes—generally priced like works of art, at up to $8,000—to sell for between $150 and $300. For each bike sold, they would donate one to grass-roots organization Bicycles for Humanity, which in turn would distribute them to communities across Africa. They called their project "Panda Cycles" (the project is now called Pedal Forward).

At CGI U, Panda Cycles would join the ranks of hundreds of other innovative and original projects, each proposed and run by college students. From GW, there were—among others—plans to help restaurants donate unsold meals to homeless shelters, create mobile libraries in Central America, and educate women in Rwanda about maternal health. On the second day of the conference, packed hundreds deep onto the floor of the newly renovated Charles E. Smith Center, students from GW and schools across the world networked and chatted about their projects—discussions from which new partnerships and possibilities quickly arose.

"A lot of people I talked to had Africa-focused commitments, and all of them in some way needed a transportation aspect," Mr. Wilkins says. "We spoke with a few people that wanted, once we were up and running, to link up with us to provide that transportation. For example, some were setting up health clinics—but health clinics being local and very centralized, the workers there need some way to get around to other villages." A Panda Cycle, he pointed out, would solve the problem.

The Pedal Forward team—Chris Deschenes, Jon Torrey, and Matt Wilkins—won the "Commitment to Action" competition with its proposal for a bamboo bike as a practical, concrete solution to a social problem.

William Atkins

While students made connections with their peers, they also had the opportunity to meet with and learn from heavy hitters in social entrepreneurship. At the opening plenary session, former President Bill Clinton conducted a panel that included, among others, former Secretary of State Madeleine Albright and pop superstar Usher, the chairman and founder of Usher's New Look Foundation.

"There was nothing crazier than watching Usher right next to [GW President] Steven Knapp right next to Madeleine Albright," Mr. Deschenes remembers, laughing. "But that's what made [CGI U] great—you could have this breadth of experience onstage, but they were all on the same page."

That was just the beginning. Participants in CGI U could attend workshops and lectures on topics from promoting nonprofits via social media to working against genocide. And the weekend was punctuated with star-studded panel discussions—including a memorable one with Twitter founder Biz Stone on the importance of failure as a learning experience and a way of measuring risks.

"Failure looks great on a résumé," Mr. Stone said. "All of the experience you get, the ups and downs and highs and lows of that are usually awesome. That's awesome that you tried that. That's the kind of spirit we want."

"He told us that at Facebook headquarters there's a wall that just says, 'Fail Harder,'" says Mr. Deschenes. "I love that."

Former U.S. President Bill Clinton praises the Panda Cycles team, made up of GW students, onstage.

Jessica McConnell Burt

That Saturday afternoon, the members of the Panda Cycles team were tense. At 3 p.m., the winner of CGI U's bracket challenge—a weeklong competition to choose the winning proposal with online votes from around the world—would be announced. Panda Cycles was in the final round, head to head with Tufts University's Village Zero Project, which aims to create a tracking system for outbreaks of cholera in Bangladesh. Mr. Deschenes, Mr. Torrey, and Mr. Wilkins had been summoned to Lisner Auditorium but not yet told the results. That was when they encountered Jon Stewart, also waiting backstage before his conversation with President Clinton would close the conference portion of the weekend.

"He was really supportive of the project," says Mr. Wilkins, who says he also asked Mr. Stewart to put him in touch with Neil deGrasse Tyson, a renowned astrophysicist and frequent guest on The Daily Show, who Mr. Wilkins hoped would speak at the engineering school's commencement. "That part didn't work out," he laughs.

The bracket challenge, however, did. A few moments later, the Panda Cycles team was onstage with Mr. Stewart and President Clinton, accepting a signed basketball as a "trophy" and hearing the former president praise their initiative as "possibly the beginning of a sustainable livelihood for people all over the world."

"We really had to pinch ourselves," Mr. Deschenes says. "When we started this, it was just three guys and an idea, and what's happened since then is definitely not what we expected—in a good way. I mean, we didn't reinvent the wheel. We just took two of them and attached them with bamboo and made bikes."

They may have not reinvented the wheel, but they are among many at GW who are using their ingenuity, skills, and free time to make the world a better place, says GW President Steven Knapp.

"This generation of students is marked by a deep commitment to serve, not just at GW, but worldwide," President Knapp told CGI U attendees. "And I was inspired by the variety and creativity of our students' commitments to action."

Chelsea Clinton takes part in a service project that was part of CGI U. Participants helped with home repairs in Northeast D.C. and assembled care packages for American troops. Adam Schultz/Clinton Global Initiative

William Atkins |

Elise Apelian/Clinton Global Initiative

Jessica McConnell Burt |

GW Students at CGI U

The Panda Cycles team members were among many GW students to contribute their talents to CGI U. Students from across the university proposed a variety of plans to improve their world.

Jessica McConnell Burt |

Sam Smith/Clinton Global Initiative

|