The Presiding Professor

Through co-teaching a weekly constitutional law seminar last semester, Justice Clarence Thomas helped GW Law students find the stories behind fundamental Supreme Court cases.

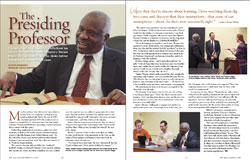

Most law students who refer to the lessons they've learned from U.S. Supreme Court justices are speaking figuratively. But in the case of GW's Constitutional Law 6399-14: Leading Cases in Context, co-taught by U.S. Supreme Court Associate Justice Clarence Thomas and Professor Greg Maggs, students had more direct contact with the source.

Rather than synthesizing lessons from a judge's recorded summary, students in the weekly seminar examined primary sources to find the human stories behind famous cases. "At the end of the course, each student picked another famous Supreme Court case and then wrote his or her own history of it," Professor Maggs explains.

The course's structure did not follow the "textbook" method: reading an abridged Supreme Court opinion, parsing that opinion for a rule, and then compiling the rules studied over the semester into an outline in preparation for a final exam. Instead, students examined the primary sources that informed the opinion itself: transcripts, interviews, personal correspondence, and other historical documents.

Justice Thomas became a familiar sight around the Law School during the fall semester, as he co-taught a seminar with his former clerk, Professor Maggs.

Justice Thomas is quick to say, however, that he was not trying to rebel against the traditional model. "Don't knock outlines; that's what got me through [law school]," he says with a laugh.

But he is convinced that it takes more than an outline to make good lawyers. More important, in his view, are the values of thoroughness and humility that come from an exhaustive study of each case.

"I've been at this a long time," he says, "and nobody has the Gospel on [any case]. You're always looking for answers."

The justice's most prominent trait was certainly not a sense of his own impact. "I did not expect how loosely Justice Thomas would wear his identity as a Supreme Court justice," says third-year student Harsh Voruganti, who says he sensed that "[Justice Thomas'] identity as a Supreme Court justice was less important to him than was his identity as a Nebraska [football] fan."

"We're all learning this together," says Justice Thomas, who in person is genial, forthcoming, and contagiously enthusiastic about the class and the students he feels "privileged" to share it with. "I may know slightly more about the history of the cases, but what I'm really interested in is learning more about them. So [Professor Maggs] and I are learning it together, and we're learning it with the students."

Co-teaching the course reunited Justice Thomas and Professor Maggs; Professor Maggs clerked for both Justice Thomas and Justice Kennedy.

Professor Maggs agrees—"and I wrote the textbook," he adds. "A lot of things that went on in these cases you wouldn't know, and couldn't know, just by reading the Supreme Court opinion. Until you get a much more complete, thorough history of the case, you just miss out on it."

"Justice Thomas clearly really enjoyed the class, specifically interacting with students," says class member Brittany Warren. "We all knew that we were going to have to really step up our games to take advantage of the opportunity. … He turned out to be incredibly warm and funny, and naturally, very insightful. … His enthusiasm for what we're trying to accomplish in the class really came through."

The Supreme Court justice says the best part of teaching is watching students grow. "I love that they're sincere about learning. I love watching them dig into cases and discover that their assumptions—that none of our assumptions—about the facts were necessarily right."

Justice Thomas' "willingness to engage with students as intellectual equals" was a major high point of the class, says Mr. Voruganti, who recalls having once suggested "that a law requiring students not to study more than six hours a day would be constitutional."

In response, he says, "Justice Thomas hit me with a series of hypotheticals regarding fundamental due process rights and asked me just how much deference I was willing to offer the legislature. After my rather garbled response, he graciously accepted my point as a good one and used it as a jumping-off point for the discussion. It's the closest I have gotten to being in an oral argument with a Supreme Court justice."

What he tries most to communicate to students, says Justice Thomas, is that they should bring "humility" to the art of lawyering. "You've got to approach the law with a sense of modesty and with thoroughness."

What he tries most to communicate to students, says Justice Thomas, is that they should bring "humility" to the art of lawyering. "You've got to approach the law with a sense of modesty and with thoroughness."

That care and completeness is something the justice values outside the classroom as well. "All we're asking you to do is to look at [cases] honestly and thoroughly, so you have a full understanding of them," he says. "The rule I have with my law clerks is that they will leave their job with clean hearts, clean hands, and clean consciences. Because we're going to do things in a way that we think is [thorough]. Does that make us perfect? No. But there's no moral turpitude to [making] mistakes. That's just human imperfection."