Saving Grace

When treasures of the art world have gone missing, Charles Hill, BA '71, has made a career of bringing them back

"Thanks for the poor security."

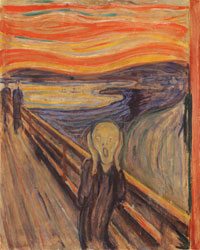

That note, written on the back of a postcard, was one of the few things the burglars left behind—that and a broken window, wire cutters, a ladder to the ground below, and an empty space where Edvard Munch's iconic painting The Scream once hung in Norway's National Gallery.

The all-too-easy theft of the Norwegian treasure in February 1994 was a slap in the face; the note a little extra mud in the eye, a schoolyard taunt. But for Charles Hill, then a detective with London's Metropolitan Police who was called in to help with the investigation, the note also offered a clue.

"It wasn't as if you're dealing with some heavy-going bunch of mafioso or anything," Hill recalls thinking of the note. "Just some arrogant"—ahem—"[not-so-nice reference to derrière]s."

In fact, that's how Mr. Hill sees the vast majority of this criminal element. "It's ambitious crooks," he says through a polite British accent. "Most of them are complete [bleep]s; ignorant [bleep]s. Ignorant and arrogant [bleep]s."

He pauses.

"Once again, you may have trouble getting that into your article."

If Mr. Hill sounds salty and irritated—angry, even—that's because he is. He has zero tolerance for the pilfering of cultural history.

The bad news is that the ancient crime of art theft shows no signs of stopping. The past year alone has seen the taking of works by Pablo Picasso, Henri Matisse, and others in a single Paris heist, and a Vincent van Gogh pinched in Egypt.

It's fortunate, then, that Mr. Hill has something of a knack for recovering stolen masterpieces.

Richard Ansett, National Portrait Gallery Permanent Collection, London

The man who has been called "Britain's premier art sleuth," "bookish and genial"—and, it seems safe to say, more than a few impolite phrases—also has been known to some on the other side of the law as "Christopher Charles Roberts," including to those entangled in the Munch caper.

Many times during his 20-year tenure with London's Scotland Yard, Charles Hill, 63, conducted his most serious business—whether chasing art, drugs, or counterfeit bills—from behind a nom de guerre like that one, often outfitted with a mid-Atlantic American accent and the money-soaked panache of a corrupt "wheeler-dealer type," he says; a character he describes as "completely amoral."

It was this fabricated eccentric—posing as a buyer—that starred in a 1993 sting in Antwerp, Belgium, that netted masterpieces by Johannes Vermeer (Lady Writing a Letter With Her Maid) and Francisco de Goya (Portrait of Dona Antonia Zarate), among other works. The paintings had been stolen seven years prior from the estate of Sir Alfred Beit, outside Dublin.

The theft, by Irish mobster Martin Cahill and his men, included 18 paintings. At the time, the stolen Vermeer was one of only two privately owned works by that painter—there was Sir Alfred Beit's, and then there was the one belonging to Queen Elizabeth II. Altogether, only some three dozen Vermeers are in existence, each of them coveted.

The return of the paintings was "the most exciting thing that has happened here since the robbery itself," the administrator of the collection told the New York Times in 1993. "It's brilliant."

For Mr. Hill himself, it is the biggest case of his career to date and perhaps the most satisfying—orchestrating the return of a spectacular endangered species and a Goya that he deems nothing shy of "magnificent."

The next year, The Scream disappeared from Norway's National Gallery. Of four versions of that painting, this one is considered the most important.

At the first reliable hint that the painting's whereabouts might be known, Scotland Yard and the Norwegian police put Mr. Hill into action. Posing as a credentialed representative of the J. Paul Getty Museum, of Los Angeles—well-known for its cavernously deep pockets—Mr. Hill (as "Chris Roberts") fed the idea to a group of middlemen that the Getty would gladly pay them to return The Scream to the National Gallery, which in turn would agree to lend the painting to the Getty.

They bought the ruse—hook, line, and sinker.

Even with The Scream safely in his hands, though, he says there was—and always is—"a certain trepidation" that momentarily washes over him. "I don't want to be flush with a fake."

Impostors abound, but this was the real thing.

In both cases, at least some of the men charged would end up skirting punishment. But in his realm of police work that's beside the point. "When these wonderful masterpiece paintings are stolen," says Mr. Hill, "the paintings are more important than the people who steal them."

Edvard Munch's haunting and iconic painting The Scream.

Photo by Jacques Lathion, courtesy of Norway's National Museum of Art, Architecture and Design

For the pleasure of seeing—in their true, living color—these paintings and others once held hostage, the world owes a debt to two dabs of paint.

They are the eyes of the title figure in Edouard Manet's The Old Musician, painted in 1862 and held in the collection of the National Gallery of Art in D.C. For Charles Hill, those pensive eyes that curiously stare back toward the viewer explain the rapture of art.

"There's a piece of music by Mozart that, I once read, can almost give you an argument for the existence of God," he says. "If you look at the old musician's eyes you can get the same sense of feeling about that and the meaning of life."

He points to brilliance, as well, in Gilbert Stuart's 1782 painting The Skater (Portrait of William Grant), and French painter Jacques-Louis David's The Emperor Napoleon in His Study at the Tuileries, from 1812 (even if Mr. Hill finds the emperor himself to be "a pernicious little [bleep]").

Asked why he devotes his investigative prowess to solving art crimes rather than, say, homicides, Mr. Hill responds that just as individuals are worthy of protection, so too are their cultures.

And much like those who protect people, he finds hardest about his job the simple indifference of others. "There is a terrible indifference," he says. "And even pictures that a lot of people wouldn't care to buy—like, for example, Edvard Munch's The Scream, a lot of people would say, 'What the hell is that about?' But when you see the thing you realize it is quite a masterpiece. Munch himself was an odious creep, but the painting itself is a masterpiece."

It was Mr. Hill's mother, Zita, who encouraged this appreciation. A dancer from a well-to-do English family, she met her American husband, Landon Hill, during World War II in England, where he was serving in the U.S. military.

When Mr. Hill was a child, his family hopscotched through England (his country of birth), Germany, and the United States, including periods in the Washington, D.C.-area, which he considered his hometown for nearly 20 years.

"My mother dragged my two sisters and me around to all the art galleries she could in Western Europe and the Eastern Seaboard of North America. As a consequence of that," he says, "I had sort of inculcated into me—reluctantly as a young boy—that these things are worth looking at, and seeing, and knowing about."

In 1967, after two years at Trinity College in Hartford, Conn., Mr. Hill left school and volunteered for U.S. military service as a paratrooper in the Vietnam War.

This courting of danger—his zeal for facing chance and daring it to blink first—is a trait that leaped out at journalist Edward Dolnick in his 2005 book about Mr. Hill and the Munch case, The Rescue Artist. He found Mr. Hill "temperamentally allergic to blandness and routine."

"I think the real reason Charley volunteered for Vietnam," a friend told Mr. Dolnick, "is that he finally figured out that nobody gets killed playing football."

For his part, Mr. Hill doesn't necessarily disagree: "That's where the action was," he says. "Why spend two years in the Army and spend it in Fort Bragg, N.C.?"

He also concedes, though, that he "felt very strongly that the wrong people were going to Vietnam"; that his middle-class, college-educated peers were passing the buck, leaving service to the poor and disenfranchised.

So Mr. Hill had put his money where his mouth was, and he was lucky not to choke on it. On that point, he doesn't disagree either.

"You spend a lot of time thinking about what it is in life that's important," Mr. Hill says of the year he spent in the jungles of Vietnam. "I developed an interest in revisiting these places that I'd been with my mother and sisters. And the career took off from there."

First, though, he would return to D.C. and complete a bachelor's degree at GW in 1971, with the help of the G.I. Bill and, later, a scholarship.

Attending history courses at GW by day, Mr. Hill pulled night shifts as a security guard at office buildings near campus. In his free time on Sunday mornings, he made a point of attending the National Gallery of Art's big-screen showings of the acclaimed, 13-part series Civilisation from the BBC and art historian Kenneth Clark.

The programs, about the emergence of Western culture, left such an impression on Mr. Hill that four decades later the mention of it opens the door to a stream of excited remembrances, down to the titles of specific episodes.

In those years, Mr. Hill was "totally unique; wonderfully, happily unique," recalls Frank Atwood, BS '76, a friend and fellow Vietnam veteran who rowed crew with Mr. Hill at GW. "He could be obnoxious to some people, no doubt about it. But at the same time, great fun. A real pleasure."

He won a Fulbright scholarship and headed to Ireland for more schooling, and over the course of five years tried on several hats, from school teacher in Belfast to theology student in London, before joining Scotland Yard.

Over the course of two decades, he held several positions with the police, including detective chief inspector in charge of the Art and Antiques Squad in the mid-1990s. But eventually he felt claustrophobic within the organization of the Metropolitan Police, just as the strict structure of the church prevented him from pursuing the clergy.

"For Hill, the pattern never varied," wrote Mr. Dolnick, the biographer. "Talent and brains would lift him up, and restlessness and rebelliousness would send him tumbling back down."

Titian's Rest on the Flight into Egypt, which Mr. Hill recovered at a bus stop.

Titian's Rest on the Flight into Egypt, which Mr. Hill recovered at a bus stop.

Copyright Longleat Enterprises. Reproduced by permission of the Marquess of Bth, Longleat House, Warminster, Willshire, Great Britain.

But, he wrote, all the peculiarities that made Charles Hill a love-him-or-hate-him guy—"the chafing at authority, the posh accent, the tendency to drip polysyllables, the arcane interests, the 'outsiderness' in general"—they all made for one helluva clandestine cop.

"It's basically method acting without a script," Mr. Hill says of undercover work, referring to the style of acting fueled by an actor's own emotional experiences.

Success, he found, lay in meticulous preparation, and then mental savvy and a sufficiently combustible attitude to handle everything that can't be learned or planned-for in advance. To minimize risk, he would resist spinning too many lies (the more details there would be to keep track of) and eschew surveillance teams, when possible—even a gun. "Hardware will only let you down," Mr. Hill told Edward Dolnick.

In 1996, for instance, the pursuit of a "cornucopia" of stolen treasures, including the painting The Old Fool by Lucas Cranach the Elder, had led an undercover Mr. Hill to a below-ground garage in Germany. German police had outfitted him with a briefcase designed to give the signal, with the turn of a knob, that he was ready for the cavalry to rush in—which would've been great, had the signal worked below ground.

Under the circumstances Mr. Hill stalled for time, chatting away with a mob of gangsters, until the police, without a signal, began to fear for the worst.

"Suddenly," he says, "two great bears of cops with short hair appeared and they pulled out their 'Dirty Harry specials,' and

this horrible gangster and I were laid out on the ground and handcuffed. As the guy handcuffed me—he was a big guy, looked like Arnold Schwarzenegger—and it was great because in his Arnold Schwarzenegger broken English he whispered in my ear: 'Good verk.'"

People steal art for the same reasons that they do lots of things: for vanity, for money-lust, for respect. Or, simply because it's there. Why not?

The theft of world-renowned art is especially puzzling, because resale on the open market is so incredibly difficult. Reputable buyers wouldn't touch a fire-sale on The Scream with a 10-foot pole, especially not after reading that one was recently stolen.

Mr. Hill and other experts chafe at romantic notions of wealthy, reclusive buyers who would pay handsomely to secretly enjoy the company of a work of art, locked away for their eyes only. No matter, wrote Mr. Dolnick, because "what's important is that the thieves do believe it."

Short of that, though, paintings can end up as underworld currency for barter, down payments, or settling debts.

As art changes hands underground, rumor and hearsay about a piece will bubble to the surface anew, where Charles Hill is all ears and constantly in contact with sources. With any luck, he can reach a work of art swiftly enough to save it from ruin, whether accidental or deliberate.

He is a freelance sleuth now and a security adviser, having left Scotland Yard in 1997 and following a stint as the risk manager for an art insurance firm. Based out of Richmond, Surrey, 10 miles or so from London, Mr. Hill no longer works undercover; "too dangerous," he says. That's not to say, however, that it's affected his résumé.

In 2002, he secured the return of a painting by Titian, the celebrated 16th-century Italian. With a reward on the table, an informant uninvolved in the crime—the law, he says, prevents dealings with a picture's thief—led Mr. Hill to a London-area bus stop, where Titian's Rest on the Flight into Egypt sat cardboard-wrapped and stowed inside a plastic shopping bag.

In 2003 and 2005 he retrieved jewels and gold pieces from the 16th century that had adorned an ancient figure in a cathedral in Sicily.

Edouard Manet's The Old Musician, painted in 1862, is perhaps the piece of art that moves Charles Hill more than any other. The eyes of the musician, he says, stir with in himself ruminations on God and the meaning of life.

Edouard Manet's The Old Musician, painted in 1862, is perhaps the piece of art that moves Charles Hill more than any other. The eyes of the musician, he says, stir with in himself ruminations on God and the meaning of life.

National Gallery Art (Washington, D.C.), Chester Dale Collection

Other, more perennial cases also consume considerable amounts of Mr. Hill's thought and time, as he digsfor details and chases leads. All three cases appear on the FBI's top-10 list of outstanding art crimes: Caravaggio's Nativity with San Lorenzo and San Francesco, stolen in 1969 in Palermo, Italy; Paul Cézanne's Boy in the Red Vest and Edgar Degas' Count Lepic and His Daughters, taken in 2008 from the E.G. Bührle Collection in Zurich, Switzerland; and the 12 paintings—including a Vermeer and three Rembrandts—stolen in 1990 from the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum in Boston.

That heist is considered the largest art theft in history, and in August the new head of the FBI office in Boston said solving the case is one of his top priorities.

Equally pressing for Mr. Hill are concerns over the rise of what he calls the "theft by destruction" being practiced by terrorists around the world: from the shattering of two ancient and towering Buddha statues in Afghanistan in 2001, to a double suicide-bombing this past July that killed dozens at one of Pakistan's most important Sufi Islam shrines, and attacks at other sites.

"I feel as if we're entering a new phase of iconoclasm from Islamic extremists," he says, "and we've got to prepare for it." In particular, he fears London will be in the crosshairs when the 2012 Olympic Games come to town.

If past is prologue, then there may be reason to worry, not just for important buildings but art, as well. As Mr. Hill points out, there have been big scores by burglars when the popular attention was otherwise occupied: The version of The Scream that he recovered had vanished early morning on the opening day of the 1994 Olympics held in Lillehammer, Norway, and the Titian he brought back was poached on Twelfth Night; a Cézanne was stolen in the wee hours of Jan. 1, 2000, in England; the Gardner Museum heist in Boston occurred on the night of St. Patrick's Day; and a Rembrandt went missing during the British holiday Guy Fawkes Night.

The police, he said recently in a presentation to a security conference, will have plenty to look after in merely securing the Olympic infrastructure and transportation lines.

"London's great collections and buildings outside of the Olympic circus rings will need to fend for themselves," he said. To do that, he suggests cultural and religious sites draw from their volunteer networks and begin organizing plans.

It's a warning Mr. Hill vows to continue pushing into the public consciousness as the Olympics draw ever closer.

After all, he knows the painfully simple truth about our cultural monuments, about the music that saves us, and about the art that transcends beauty: "Once it's gone, it's gone."