The Learning Curve

As longtime partners in education, GW and a D.C. public high school have mastered the mutual relationship.

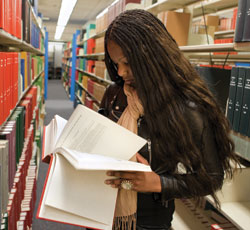

In skinny jeans and brown leather boots, Sarah Hillware stakes out a study spot at Gelman Library. It’s Friday, and she has a date with her biology book.

Ms. Hillware, who wants to be a neurosurgeon, spent the past week learning about American food history in a seminar course, reading verses at a poetry slam, and selling water bottles for a student organization. As she clicks through a packed electronic calendar on her phone and slips a bag full of books over her shoulder, Ms. Hillware looks like any other GW freshman.

Except she’s only 16.

Ms. Hillware is one of about a dozen high school juniors getting a head start on higher education through GW’s new Early College Program, a collaboration that allows secondary students to earn dual credits for their diploma and an Associate of Arts degree from GW’s Columbian College of Arts and Sciences, tuition-free. Selected through a rigorous application process, the students attend the university full time and take four or five classes a semester.

During a period when public officials are focused on ensuring America’s education system is competitive in a global economy, GW’s newest program with D.C. Public Schools bridges the secondary school experience with the resources and rigors of higher education. It’s also the chance of a lifetime for the teens involved, some of whom hail from the neediest D.C. neighborhoods.

Sarah Hillware, a junior from School Without Walls High School, is earning her associate’s degree for free at GW through the new Early College Program.

William Atkins

Although the transition to college academics has been a learning process for Ms. Hillware, the campus is familiar. She and the other teens in the cohort are students from School Without Walls, a D.C. public high school that has been located on GW’s campus since 1971. The Early College Program is just the most recent partnership between the university and School Without Walls—for years, the two have worked together on facilities sharing, graduate teaching internship programs, and, most recently, a development project that allowed both schools to gain new state-of-the-art buildings. The relationship of the partners runs deep, and officials on each side say they benefit from working together.

“It’s a reciprocal relationship,” says Mary Futrell, MA ’68, EdD ’92, dean of GW’s Graduate School of Education and Human Development, which places GW graduate interns at School Without Walls to learn teaching practices.

A College Crash Course

It’s 10:45 on a Tuesday morning and Suwratul Abdullah is early. After an hour-long commute on the Metro from Southeast D.C., he’s still listening to his iPod as he walks into health class at GW’s Old Main building and takes a seat.

Mr. Abdullah, a 16-year-old who took four classes at GW during the fall semester, hasn’t missed a class yet, but he knows that he can work on his studying skills. “I’m a procrastinator,” says Mr. Abdullah, who wants to be a graphic design artist and plans to take a digital arts elective at GW. “In college classes, you have to maintain your schedule; you have to regulate your own lifestyle. So I’m working on my weaknesses. These classes force me to do that.”

The stakes are high for Mr. Abdullah of Southeast D.C. and the 13 other School Without Walls juniors who are the first cohort to begin the program. Tuition fees of an estimated $100,000 are waived.

“My mom told me, ‘This is a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity,’ ” he says. “I’m really serious about classes because I understand it’s a big responsibility.”

GW’s Early College Program is the first partnership of its kind in Washington, D.C., and one of a growing number across the nation that offers high school students a chance to earn an associate’s degree, a postsecondary academic degree recognized by employers and higher education institutions. University officials and School Without Walls administrators discussed and planned the GW Early College Program for almost three years, taking notes on other college/high school partnerships around the nation and working with D.C. Public Schools to ensure certain GW courses match the same benchmarks for high school graduation requirements. Through the program, GW has an effective recruitment tool for some of the area’s brightest teens, while the students can choose to finish their bachelor’s degree at GW or take their credits to another institution, making college more affordable and, for some, more attainable.

Ms. Hillware wants to be a neurosurgeon and says GW is her college of choice.

William Atkins

Taking college classes as a high school student is nothing new; there has been a trend in teens taking college courses since the development of Advanced Placement classes in the 1950s. But there is a particular need for the Early College Program, which creates a more fluid relationship between high school and college academics for those urban students who are typically underrepresented in postsecondary education, says Sheila Harris, BA ’74, a former guidance counselor, teacher, and principal at School Without Walls. Dr. Harris, who is director of the Early College Program at GW, explains that some students are yearning for the challenge.

“As a counselor and a principal, I saw a common thread. By the time these kids are juniors and seniors, they teeter on being bored. Many of them have completed their high school requirements, and they are waiting to graduate. For some students, it becomes a wasted senior year,” says Dr. Harris, who was an early organizer and advocate of the program. “Working with School Without Walls students, I saw the maturity and dedication to study, and I thought, ‘This might be worth a shot.’ ”

That isn’t to say that these high school students are abandoned to the college crowd. Dr. Harris and other GW and School Without Walls partners have built a support system to help these kids succeed, including providing mentors, donations to buy books, and a weekly seminar where students can trade advice on tutors or other resources. As for academics, the students have already been stepping up to the challenge, says Robin Marcus, a GW teaching instructor in writing who worked with the cohort last summer in a GW writing course.

“If I had expectations, it was that they would act like the juniors in high school that they are,” Ms. Marcus says. “But they were mature and attentive. They were thinking about sophisticated topics in sophisticated ways.

“I was asked to make it tough for them, so I created a challenge,” she adds. “I dealt with them like freshmen, and they rose to the occasion.”

Sheila Harris, BA ’74, director of GW’s Early College Program (standing), leads a Friday cohort seminar where students can trade advice on professors, tutors, or other resources.

William Atkins

That’s the kind of drive that draws Ms. Hillware to Gelman Library, where she studies between classes. She is taking biology for science majors, and she wants to make sure she has a quiet place to reflect on her lab homework, she says. After all, she wants to someday be a neurosurgeon, and Ms. Hillware knows what it will take to accomplish her goal.

“Your mind is a stretchy thing,” she says, pulling out her homework. “The more you expand it, the better you become.”

School Days

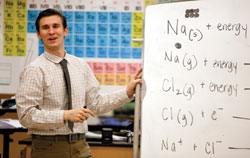

While Ms. Hillware sits down to study, GW graduate student Daniel Zielaski is wrapping up a chemistry class at School Without Walls, where he is interning as part of a master’s in secondary education program. Mr. Zielaski, who previously worked as an environmental educator for the U.S. National Park Service, felt called to the classroom, so he quit his job and applied to GW’s newest teacher education partnership. Called the D.C. Urban Teaching Residency Academy, the program allows interns to complete an intensive one-academic-year residency in one of three D.C. public schools, including School Without Walls. The residency, modeled after a medical residency where interns work full time in their fields, is designed to close the gap between teacher education and teaching practice in urban schools, where educator turnover rates are high. It is a partnership between GW’s Graduate School of Education and Human Development, the National Commission on Teaching and America’s Future, and D.C. Public Schools.

At School Without Walls, Mr. Zielaski is quickly adapting to the rigors of teaching because he has a steady support group: The teacher with whom he is working is a GW graduate, as are at least four other teachers and counselors at the school—educators he feels comfortable talking with as he experiments with the learning process. When class is done for the day, Mr. Zielaski walks down the street to his own classes at GW, where he talks with professors about what did or didn’t work with his students.

“The biggest advantage to this program is that something I learned last night I can implement today,” he says. “Maybe the strategy is great, or maybe it flops, but it’s a very practical approach to knowledge.”

Since the early 1980s, School Without Walls, a humanities magnet school located directly beside GW’s Graduate School of Education and Human Development, has provided real world classroom experience for GW graduate teaching interns, and a network of alumni who work or teach at the school is beginning to grow. GSEHD Dean Futrell says the partnership is more than just proximity; both schools are working toward a common goal.

GW master’s student Daniel Zielaski teaches chemistry at School Without Walls as part of his teaching internship program. School Without Walls, a humanities magnet school located on GW’s Foggy Bottom Campus, provides real world classroom experience for GW students.

William Atkins

“We work with them on professional development of teachers and curriculum in their school, and, as a result, they help us improve the quality of our teacher educator programs,” Dean Futrell says. “The end product, we hope, is a quality education for everyone involved.”

The educational collaboration doesn’t end there. GW faculty members, staff members, and graduate students regularly guest lecture in School Without Walls classes. GW professor James Miller, chair of the Department of American Studies, helps to coordinate the American Studies program at the school with the help of GW students, who plan and lead field trips across the city. GW staff member Bernard Demczuck, assistant vice president for D.C. Relations, has lectured at the school for more than a decade and teaches a weekly African-American history course. In addition, School Without Walls students, faculty members, and staff members can take GW courses, tuition waived.

GW and the school also share facilities, with high school students using the GW theaters for drama class or the university’s work out center for physical education class, and college students attending GW courses at the School Without Walls building at night. In October, first-year School Without Walls teacher Meg Kennedy, MEd ’09, snagged tickets for a few students to see Secretary of State Hillary Clinton and Secretary of Defense Robert Gates discuss defense and diplomacy during an event at Lisner Auditorium.

“GW definitely provides those opportunities to connect the outside world with what we’re learning in the classroom,” says Ms. Kennedy, who teaches government. “There are a lot of opportunities that I just wouldn’t have as a teacher anywhere else.”

Mr. Zielaski says he has a steady support system at the high school, where a growing number of GW alumni teach. His mentor teacher, Cristal Piper, MA ’09, MHSA ’00, is a GW alumna.

William Atkins

GW officials say they value that connection with School Without Walls students, who come from all areas of D.C. to attend the city’s star magnet high school. The students are academically talented (they must apply to the school to attend), innately curious, and driven, Dr. Harris says, adding that they mature quickly surrounded by college students.

In Washington, D.C., where the school system has historically struggled and ranks among the lowest in the nation, this private-public partnership is opening doors. Through the years, 12 School Without Walls seniors have earned full, four-year scholarships to GW through the Trachtenberg Scholarship Program. The scholarships—given to the brightest D.C. students—include tuition, fees, housing, meals, and books valued at about $200,000. Those School Without Walls students who grow up around GW’s campus and watch college students throughout their everyday lives soon become academic role models themselves, for the generations to come.

That’s why Ms. Hillware, who is getting a jump start on her education through GW’s Early College Program, still stops by “Walls” every now and then to chat with friends and former teachers about what she is learning in her college courses. She will attend classes at GW for the next two years as she finishes high school, but what about after that?

“I think I want to stay here for the rest of college,” says Ms. Hillware, who turned 17 in December. “GW is like my home. Why would I leave?”