The Hunt for the 1580 Coutume de Paris

Building the French Customary Law Collection at The Jacob Burns Law Library

“The most beautiful coutumier I have ever seen.”

Never had the Jacob Burns Law Library’s book broker in France prefaced his weekly e-mail notification of auction lots with such an effusion, so naturally this breach in his typically restrained professional demeanor caught my attention. The book that had captivated him was a copy of the most important printing of the most influential of all the customary laws of France: the final revised compilation of Paris customary law, Coustumes de la Prevosté et Vicomté de Paris (Paris: Jacques du Puis, 1580). Its significance as an artifact of the legal history of France and as a source of contemporary French civil law was matched only by its rarity, hence the remote likelihood ever of chancing upon a copy available for sale. And yet here was the opportunity to purchase at auction the book which indisputably would be the cornerstone of our French Collection, and possibly the most important book of the Law Library’s entire collection.

In 1500, the northern region of France was generally subject to customary law (pays de coutumes), with the southern areas governed largely by the written law of the Roman law tradition (pays de droit écrit).

Nonetheless, it was precisely the importance and scarcity of this 16th-century compilation of the customary laws of Paris that converted the pattern of our weekly auction rituals from routine to byzantine. When faced with the opportunity to buy an exceptional book at auction, our normal approach would dictate setting a maximum bid high enough to afford the library a reasonable chance of success. In instances where the auction expert’s estimated hammer price is higher than we are in a position to offer, we decline to enter the bidding process. Auctions aside, vigilant booksellers regularly offer the Law Library many fine (and correspondingly expensive) books that would be appropriate and desirable for our Special Collections—if funds existed to buy them all. Acquiring rare books is necessarily a selective process, and building special collections can be a gambler’s game: One passes on a coveted book when funds are slack, betting either that its cost will prevent an easy sale to another buyer (in the hope that the book will stay put until funds are more plentiful), or that another copy will surface in the future. As the level of desirability and rarity increases, however, happening upon another copy in one’s lifetime becomes far less likely, and the regret incident to rejecting such a prize weighs heavily. In the case of exceptional materials, sometimes the rules must be broken.

There was no doubt that this book belonged in the “exceptional” category and is better described as “unique” because of its attributes and provenance. The single largest component of the Law Library’s French Collection is its collection of French customary law, or coutumes; a subject search in our online library catalog, JACOB, for “Customary law—France” and its related subjects, at the time of this writing, yields 1,030 entries, suggesting that ours is one of the strongest collections of French customary law, not only in this country, but in the world. Acquiring the 1580 Coutume de Paris would be akin, in mountaineering terms, to reaching Everest’s summit.

The French Customary Law Tradition

In 1500, approximately two-thirds of the area of what today is modern France was governed by rules still resting in oral tradition: the coutumes, or customary practice. In the north, the pays de coutumes (country of customs), coutumes prevailed as the dominant source of law; the southern lands of France formed the pays de droit écrit (country of written law), where Roman law survived as the primary legal framework. In reality, the distinction between the law applied in the north and the south of France was not so absolute as this, since gaps in either custom or in Roman law typically were filled by borrowing from the other tradition, and consequently neither segment of France was governed altogether by either of the two systems. Originally, as its name suggests, la coutume consisted of practices which developed spontaneously and were followed by the populace, becoming obligatory despite remaining oral: They did not enter into force as written enactments by a law-giving authority and thus carried no official sanction.

Le Coustumier dAniou et du Maine (Paris, 1486). The second incunable printing of the customary law of Anjou and Maine, and the only complete copy of the two recorded in the United States. Bound in red morocco with gilt edges, marbled end leaves, and morocco slipcase, this binding ensemble appears lavish, but its primary goal is to provide superlative protection for its rare contents.

Jessica McConnell

Voltaire’s widely disseminated witticism that “When you travel in this kingdom, you change legal systems as often as you change horses” was accurate in spirit in light of the fact that by the twilight of the Ancien Régime in France, there existed 65 general coutumes and more than 300 local coutumes. The divergence between customs in different districts, and local variations, combined with their character as an oral tradition, had created legal confusion over the course of many years. In the event of litigation, a process known as enquête par turbe established the laws in question: A group of respected men hailing from the locus of the coutume was convened to decide what the law actually was and to inform the court of its decision.

Documenting French Customary Law

Although privately coutumes had been recorded occasionally beginning around the 12th century, and a handful of official and semi-official compilations were assembled in the 13th century, no official requirement existed in France for documenting customary law until the 15th century. The inevitable necessity of recording the coutumes was addressed by King Charles VII. By his promulgation of the celebrated Ordonnance de Montils-les-Tours in 1454, he ordered that the customs, usages, and rules of practice of every district in the kingdom be reduced to writing by the local inhabitants, brought before the king, and examined by his council or by the Parlement preliminary to publication. Though response to his new law proved slow, Charles VII had established the official position on recording customary law, paving the way for succeeding monarchs to continue the process of documentation.

The beginning of the 16th century saw vigorous redaction activity as many coutumes were documented and edited, culminating in publication of the Coutume de Paris in 1510. The influential and erudite jurisconsulte Charles du Moulin in 1539 made the Paris coutume the subject of an extensive commentary, thus assigning to it a lasting prominence among the laws of France, and thereafter it served as a model for redacting other coutumes, forming essentially a common law of customs. Its final revised compilation of 1580 was the crowning achievement of the documentation endeavor, and this version of the Coutume de Paris became the most influential of all the customary laws of France.

On vellum, the painted and gilded arms of owner Mathieu Chartier, one of the five jurisconsultes commissioned to redact the Coutume de Paris.

Courtesy of The Jacob Burns Law Library

The authority of the 1580 Coutume de Paris extended far beyond the confines of Paris itself, due in part to the intellectual reach of its drafters, the finest legal minds of the era, and to its association with the Parlement of Paris, the most powerful legal body in France, with a jurisdiction that extended to nearly half the realm. The crown regularly decreed the Coutume de Paris in force in any new area annexed to the realm, including colonies. In the New World, Louis XIV extended the law in 1663 to the vast territory of New France, which blanketed a significant part of North America including Canada, the Great Lakes region, and Louisiana reaching from north to south roughly along the Mississippi Basin. Many of its provisions were incorporated, often verbatim, into Napoleon’s Code Civil of 1804. Through the Code Civil, introduced widely throughout Europe and Latin America during the 19th century, either in toto or as a model code with country-specific modifications, the 1580 Coutume de Paris continues today as a living legal presence.

Chasing the 1580 Coutume de Paris

The threshold challenge for the Law Library in acquiring this book was the issue of cost, and we decided to take up that gauntlet, within reason. We signaled to our broker in France that we were ready, and relayed our maximum bid, which landed at about the midpoint of the substantial range of the expert’s estimate, still a very legitimate bid. However, the purchase at auction of a book of this magnitude, both in price as well as cultural importance, by an entity outside France entailed major risks. At the outset, we needed to make certain that the coutumier legally could be exported to the United States if sold to us. As an artifact of French cultural heritage, the coutumier presented two potential impediments to purchase by a foreign entity. In the first scenario, a French national museum could exercise its right of pre-emption at the fall of the hammer, thus claiming the book for its collection and short-circuiting the sale to the highest bidder. Then, even if no such museum asserted its right of pre-emption, the French government could refuse to issue a certificat de libre circulation, the document that would allow the book to leave France (actually, two documents: one that would permit the book to leave France but remain in the European Union, and another that would permit it to exit the EU). Generally, a book of substantial value would sell with the appropriate exit papers, but in this case the auction house did not request documentation, so the book would sell “bare.” After detailed e-mail discussions with our broker that continued until late on the eve of the auction, in combination with the broker’s continuing communications with the commissaire priseur (official in charge of the auction) until shortly before bidding began the next day, we concluded that the documentation impediment could not be resolved. We declined to bid.

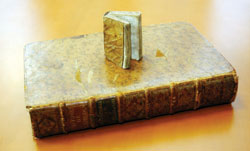

Books of French customary law came in all sizes, from pocket references to massive folios. Here the diminutive Coustumes du Pays de Normandie rests upon the imposing Les Coutumes du Duché de Bourgogne.

Claire Duggan

But what if “our” book did not sell? In fact, it did not. When the coutumier failed to attract a high enough bid, it was withdrawn from sale. However, our broker remained in contact with both the commissaire-priseur and the expert, who contacted the owner about the possibility of an authorized private sale. On the brink of negotiations, the owner decided against selling his coutumier at all. But 10 days later, thanks to the tenacity of our broker, discussions with the seller commenced. Now, however, an additional tax applied, since this sale (vente d’objet précieux) would be by an individual rather than through auction. Still working with our original bid amount, inclusion of this tax narrowed our working margin and made agreement trickier, but still feasible. Concurrently, our broker confirmed that the French government would consent to grant the proper exit documentation. When agreement was reached with the owner, our delight was guarded pending the broker’s confirmation of receipt of the exit documentation, which allowed us to tie up the financial amenities. Nearly four months after learning of the availability of the 1580 Coutume de Paris, I opened a well-padded package at the Law Library to inspect the book “in person” for the first time, and exhaled.

The Law Library’s Coutume Collection

The 1580 coutumier joins a host of rare and unusual books in the French Collection printed from the 15th through 19th centuries that includes the customary law itself, as well as contemporary commentaries and more recent scholarly analysis. The core of this collection was formed by purchases from two major European auctions of exceptional law collections: the dispersal of the Birmingham Law Society’s library (London), and the Payrat collection of the Château de Razat (Paris), in 2001 and 2002 respectively. The collection grows steadily, mostly from purchases at the French auctions that are held weekly throughout the year, with a seasonal break in August. It includes works by the major commentators of the coutumes, including Philippe de Beaumanoir (d. ca 1296); Charles du Moulin (d. 1566); Bernard d’Argentré (d. 1590); Guy Coquille (d. 1603); and Antoine Loisel (d. 1617); and represents most regions of France, from the smaller bailliages and sénéchaussées to the extensive regions subject to the Coutume de Paris. Much of the coutume collection is housed in the Rare Book Room on the first floor of the Law Library, next to the Tasher Great Room.

Title page of Les Coutumes des Duchez, Contez & Chastellenies du Bailliage de Senlis (1540), showing the rubrication and illuminated initials characteristic of this work. The Law Library’s copy is one of two recorded in the United States.

Claire Duggan

Among the many early coutumiers in the collection are an incunable (a book printed before 1501 using movable type) and a very scarce 16th-century exemplar. Le Coustumier dAniou et du Maine (Paris, 1486), which records the customary law of the neighboring regions of Anjou and Maine in the Loire Valley, was the first book of customary law acquired by the library that also is an incunable. Although it is a “second edition” (the first, of which only a single copy survives, was printed in Angers c. 1476), as one of only two recorded copies in the United States, and the only complete copy, it is a work of extreme rarity. Les Coustumes des Duchez, Contez & Chastellenies du Bailliage de Senlis (Paris, 1540), produced shortly after the assembly for its redaction was called in 1539, is one of two recorded copies in this country. It is printed on vellum with exceptionally fresh rubricated and illuminated initials and decorations.

Coutumes for Historical Research

Because the coutumes, along with Roman law, canon law, the ordonnances royaux, and decrees of the Parlement, formed the historical basis for the development of French law, they are invaluable resources for legal scholars and other historians in their analyses of later legal developments in France. Yet the influence of the coutumes, especially the 1580 Coutume de Paris, did not come to a halt at the French border. When the 1580 redaction became law in New France in 1663, then later assumed a far-ranging presence due to its assimilation through broad adoption of the Code Civil in Europe and Latin America, it claimed a beachhead in many territories other than France, some unexpected. Indeed, in the piece of New France that eventually became Wisconsin, the Coutume de Paris formally was nullified by statute only in 1810, although this pronouncement was ignored and the Coutume remained the de facto law until a resolution annulling it once and for all was passed in 1818. Present day Louisiana, as a civil law state, is governed by many provisions drawn from the Code Civil of Napoleon, and consequently the work of French legal scholars versed not only in the Code Civil but also in its antecedents, the coutumes, can illuminate current legal analysis. Coutumes, if regarded as medieval custom reduced to writing, also can animate for the researcher long-forgotten folk practices which in turn can lead to a deeper understanding of the reasons for how laws unfolded as they did.

The 1580 Coutume de Paris was dedicated in honor of Edwin Widodo, benefactor to the Law School, in August 2008, on the occasion of his birthday.

|

|

|

Jennie C. Meade is the director of Special Collections at the Jacob Burns Law Library. For more information regarding coutumes and Special Collections at the Jacob Burns Law Library, please contact her at jmeade@law.gwu.edu or 202-994-6857.

A Closer Look: Coutumes de la Prevosté et Vicomté de Paris

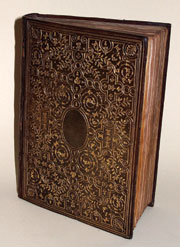

The binding style of the 1580 Coutume de Paris, known as à la fanfare, features intricate gold tooling with floral motifs and scrolls surrounding a central medallion.

Courtesy of The Jacob Burns Law Library

One of five de luxe exemplars printed on vellum for the five jurisconsultes who redacted this 1580 coutumier, our copy was produced specially for Mathieu Chartier and bears his painted and gilded arms on a vellum leaf preceding the title page. The Premier Président of the Parlement, the distinguished jurist Christofle de Thou (1508-1582), led the redaction effort with the support of Henri III. De Thou agreed with jurist Charles du Moulin’s assessment that the 1510 redaction of the Paris coutume tended to preserve legal diversity rather than enhance unification. When he became Premier Président in 1562, de Thou devoted himself to producing a new redaction of the coutume that blended linguistic precision with moderation in legal substance, seasoned by judicious addition of divers principles of Roman law. Mainly de Thou’s redaction succeeded in promoting the customary law of Paris as the common law of France and emphasizing the role of customary law in preference to wholesale adoption of Roman law. Prevailing sentiment at the time, as enunciated by jurists including François Hotman (1524-1590), favored “indigenous” French practices over Roman law; for them it was important that the general law of the land derived primarily from “homegrown” rather than imported legal sources. With the authority of the Parlement of Paris behind the effort, the Coutume de Paris became established as the model for future redaction efforts.

Title page of the Mathieu Chartier copy, a first edition, first issue of the 1580 Coutume de Paris

Courtesy of The Jacob Burns Law Library

This copy of the Coutume de Paris is bound in morocco decorated in the elaborate “fanfare” style typical of the latter part of the 16th century, a treatment characteristic of the most exquisite productions of the master gilding experts of Paris. The same binding studio also produced work for the queen of France, Catherine de Medici, and historian Jacques-Auguste de Thou, son of Christofle de Thou, noted for his celebrated scholarly library. The binding itself appears in several references and is reproduced in color in the Catalogue of English and Foreign Bookbindings (Quaritch, 1921).

Of the five original exemplars printed on vellum for the jurisconsultes, three are known today, including this copy. Ours is a striking, bright copy with a historic association and a distinguished provenance. As jurisconsulte Mathieu Chartier’s own copy, it can claim status as “unique.” This copy formerly was owned by the collector Cortland F. Bishop and sold at the Magnificent French Library auction in 1948, later selling at the auction of the Raphael Esmerian Library in 1972. This is the only copy of the five specially produced exemplars known to be in the United States.

—Jennie C. Meade