|

Julie Woodford

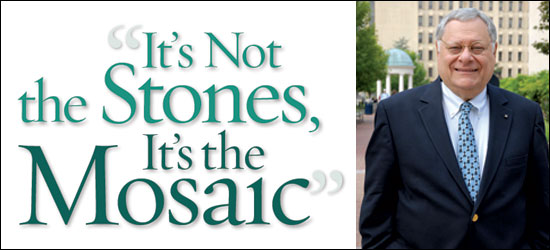

How President Stephen Joel Trachtenberg

transformed the University one brick—and

one person—at a time.

By Leslie Milk

|

Under Trachtenberg’s

leadership, GW opened or renovated nearly

a dozen buildings. Among them: The Media

and Public Affairs Building opened on the

corner of 21st and H Streets in 2001.

Julie Woodford

|

According to the District of Columbia,

Dec. 4, 2006, was Stephen Joel Trachtenberg Day

in Washington. The mayor’s proclamation

praised Trachtenberg as “one who exemplified

the spirit, vitality, and deeds that enhanced

the quality of life in the District of Columbia.”

But for The George Washington University students,

faculty, neighbors, and many in the city of Washington,

every day for the past 19 plus years has been

Stephen Joel Trachtenberg Day. Trachtenberg has

excited, exhorted, encouraged—and occasionally

infuriated—some or all of them. He wouldn’t

have it any other way.

When he came to Washington in 1987 to meet with

the search committee seeking a University president

to follow Lloyd Elliott, “They asked me

if I wanted to challenge myself at a university

whose faculty wanted to go to the next level,

“ Trachtenberg recalls. “They wanted

a president to work with them to make that happen.”

What he found was “an established university

that had room to grow and was uniquely positioned

to add to its academic reputation,” Trachtenberg

says. He also found a campus that didn’t

look like a campus and a faculty and a student

body who felt that they couldn’t compare

to the other “George” in town. In

addition, GW wasn’t taking full advantage

of one of its greatest assets—its location

at the heart of the nation’s capital. For

a Brooklyn-born city boy like Trachtenberg, that

was an opportunity to be relished. Capitalizing

on the capital would be a win-win for both the

city and the university, he believed.

Nearly 20 years later, Trachtenberg has surpassed

many of his original aspirations and, in the words

of The Washington Post, “helped

transform the school from a sleepy institution

to one of national stature.” In the process,

he became the longest-serving university president

in Washington in an era where university presidents

who last more than a decade are as rare as spotted

owls.

Many of his accomplishments are visible and quantifiable.

For example, Trachtenberg raised the University’s

endowment from $200 million to $1 billion.

But the full impact Trachtenberg has had requires

a long-range view. “It’s not the stones,

it’s the mosaic,” he says. “There

are lots of bits and pieces. Take for example

our school of public health: These things, once

you develop them, take on a life of their own

that carries them forward. That school is going

to make a contribution to the city, to the country,

and to the world.”

The state-of-the-art

Duquès Hall, home to the School of

Business, opened in 2006.

Julie Woodford

|

|

If You Build It ....

Bricks and mortar do not make a university, but

they do make a university more attractive to both

the faculty and students, Trachtenberg believes.

“It’s not an edifice complex. You

are building buildings because they are tools

for academic work and for scholarship,”

he says.

Under Trachtenberg’s leadership, GW opened

or renovated nearly a dozen buildings, including

the Media and Public Affairs Building and the

establishment within of the Luther W. Brady Art

Gallery, the Annette and Theodore Lerner Family

Health and Wellness Center, and 1957 E Street,

home to GW’s Elliott School of International

Affairs and the Department of Geography. The Marc

C. Abrams Great Hall was dedicated in 2002, J

Street Dining in the Marvin Center was completed

in 2004, and Duquès Hall, home to the School

of Business, opened in 2006. There also are five

new residence halls on the Foggy Bottom Campus.

The University substantially upgraded its library

system—there are more than two million books

in its libraries now and GW was accepted for membership

in the prestigious Association of Research Libraries.

At the same time, GW added two new campuses.

The 95-acre Virginia Campus in Ashburn, Va., opened

in 1991 with graduate programs in transportation

safety and security, public health and homeland

security, professional and executive education,

and information technology and telecommunications.

The Virginia Campus has more than a dozen laboratories

and research centers—fueled by partnerships

with Northern Virginia’s high-tech companies.

In 1997, the University acquired Mount Vernon

College on Foxhall Road in Northwest D.C. Just

three miles west of the Foggy Bottom Campus, the

Mount Vernon Campus is home to classrooms, laboratories,

interior design studios, various athletic and

recreation facilities, and residence halls.

During the Trachtenberg era, GW created the School

of Public Health and Health Services, the School

of Public Policy and Public Administration, the

College of Professional Studies, the Graduate

School of Political Management, and the School

of Media and Public Affairs.

“Buildings alone don’t teach,”

Trachtenberg said at the ribbon-cutting ceremony

for Duquès Hall, a new facility for GW’s

School of Business. “But... buildings like

Duquès and Funger Halls provide us with

the space, technology, and the modalities that

are absolutely necessary for the contemporary

study of business.”

Trachtenberg also oversaw the opening of the

new GW Hospital, the first hospital to open in

the District of Columbia in more than 25 years.

“We have world-class doctors who deserve

a world-class facility,” he says.

|

A major enhancement

to GW’s aesthetics during Trachtenberg’s

presidency is the addition of the Mid-Campus

Quad and Kogan Plaza, which have become

gathering places for students. Trachtenberg

led many improvements to the campus, including

the addition of banners, statues, and archways.

Julie Woodford

|

The location and reputation of GW’s medical

school and medical center have attracted some

very prominent patients and they, in turn, have

enabled the University to increase its treatment

and research capabilities. The Ronald Reagan Institute

of Emergency Medicine was established in 1991

to honor GW doctors for saving President Reagan’s

life. Just last year, Vice President Dick Cheney,

who has been treated by GW cardiac surgeons, and

his wife, Lynne, donated $2.7 million to create

the Richard B. and Lynne V. Cheney Cardiovascular

Institute at GW.

When he arrived at GW, Trachtenberg inherited

a campus that had expanded without rhyme or reason.

As the University grew, it had often acquired

buildings that had been designed for other purposes.

The Foggy Bottom Campus was undistinguished and

undefined. “There is no there there,”

observers quipped.

“He had a sense from the first day that

the campus had the potential for physical and

aesthetic cohesion,” says Trachtenberg’s

wife Francine Zorn Trachtenberg. “He began

to envision ways to give it form and shape.”

“We put a little lipstick on, we put a

little kohl under the eyes,” Trachtenberg

says of his campus beautification initiative.

Four large busts of George Washington now grace

the Foggy Bottom Campus. There are iron and stone

gates to delineate the campus, banners in GW colors

on light posts, new brick walkways, outdoor sculptures,

vest-pocket parks, and teak benches. The Mid-Campus

Quad with its Kogan Plaza, fountain, and tempietto

has become a gathering place for students—the

University’s outdoor living room.

Time to Teach, Time to

Research

GW has had a 25 percent increase in full-time

faculty members since 1988, including a 90 percent

increase in the number of women faculty members

and a 175 percent increase in the number of minority

faculty members. “Over time, we’ve

recruited new, young, scholarly faculty who are

committed to teaching,” Trachtenberg says.

“We’ve provided them with the facilities

they need to do their research—laboratories,

computers, and time. Time can never be underestimated

as a resource for professors.”

Improving faculty salaries was another Trachtenberg

goal achieved. Competitive salaries are a powerful

recruiting tool—GW salaries for full professors,

associate professors, and assistant professors

now rank in the 80th percentile or higher, according

to the American Association of University professors.

The number of endowed chairs has more than doubled.

GW also has seven University Professors on campus—a

designation created to attract renowned scholars.

As of Aug. 1, Trachtenberg will join their ranks

as he becomes the University Professor of Public

Service. Upon his departure from GW, this professorship

will forever become the Stephen Joel Trachtenberg

University Professor of Public Service.

During his presidency, Trachtenberg has taken

advantage of GW’s closeness to the seats

of power to lure professionals from the federal

government, medical and research centers, businesses,

and international organizations to teach at the

University on a part-time basis. Then there are

the teachers who never see the inside of a classroom—the

world and national leaders who come to speak on

campus. Because of the quality of its students

and faculty, as well as its location, GW has become

such a popular venue that a U.S. senator recently

called Trachtenberg to ask if he could speak on

campus. He had a new book coming out, the senator

said, and he wanted to talk about it at GW.

In addition, students have had opportunities

to learn from topflight broadcast journalists.

Since April 2002, CNN has aired 775 programs including

Crossfire, On The Story, and Reliable

Sources from GW’s Media and Public

Affairs Building, with 260 students serving as

production interns and 123,000 students, faculty

members, staff members, area residents, and visitors

to the nation’s capital participating as

audience members.

Scholarly research also has flourished during

the Trachtenberg years. Total research funding

has nearly quadrupled from $33 million in 1988

to nearly $132 million in 2006. GW now houses

80 chartered research centers and institutes—up

from 58 in the late 1990s.

The work of these research centers has advanced

scholarship and yielded important real-world benefits.

For example, the Ronald Reagan Institute of Emergency

Medicine had been working for a decade on international

emergency medicine, and disaster response and

prevention when disaster struck on 9/11. The institute

was able to assist FEMA and the World Trade Center,

and was involved in search-and-rescue at the Pentagon.

A $1.5-million grant from the W.M. Keck Foundation

helped to create the Institute for Proteomics

Technology and Applications. The institute benefits

from the combined efforts of three GW schools

and is already developing a protein microscope

to allow researchers to see proteins interacting

in living tissue. The hope is that scientists

will be able to use this information to develop

new treatments for diseases that cause nerve degeneration,

such as ALS, also known as Lou Gehrig’s

disease.

Research at GW runs the gamut from discovering

dinosaurs in China to digging for evidence of

King Solomon in the Israeli desert, to developing

on its Virginia Campus a Drowsy Driver Detection

System, which warns sleepy drivers to pull off

the road.

In addition to the investigative work of GW’s

faculty researchers and graduate students, the

George Gamow Undergraduate Research Fellowship

was inaugurated in 2002 to encourage talented

undergraduates by getting them involved in faculty

research projects. The Columbian College of Arts

and Sciences Luther Rice Undergraduate Research

Fellowships, started in 2003, support projects

generated by more advanced students. These kinds

of academic opportunities have helped GW to attract

the best and brightest students in its history.

“Quality Students

Bring Joy to a Professor’s Heart”

GW added two

new campuses during Trachtenberg’s

presidency. The 95-acre Virginia Campus

in Ashburn, Va., opened in 1991. In 1997,

the University acquired Mount Vernon College

on Foxhall Road in Northwest D.C. GW’s

athletics fields are now located at the

Mount Vernon Campus, pictured here.

Claire Duggan

|

|

The George Washington University is now a first

choice school for many high school students. When

Trachtenberg arrived, there were 6,389 applicants

for the freshman class, and 78 percent were admitted.

In 2006, the applicant pool jumped to 19,500,

and the acceptance rate for incoming freshmen

fell to 37 percent.

“We’ve got a buzz going on now,”

Trachtenberg says.

The ability of GW to attract a bigger and better

applicant pool is no accident. Trachtenberg has

made a conscious and concerted effort to make

GW more visible and more prestigious to a wider

group of students. “I’m going to use

words that most university presidents are embarrassed

by,” he says. “At some level, you

have to think of potential students as customers.”

To attract these customers, the University stepped

up its efforts in strengthening and expanding

academic programs, facilities, student services,

and athletic programs, among others.

Creating new academic programs geared to high

achievers was one way to demonstrate GW’s

capacity to challenge top-ranked students and

show that a big school could think small. The

University Honors Program began in the mid 1990s

with classes of no more than 20, special seminars,

and provocative topics like “The Politics,

Philosophy, and Economics of Poverty.” In

2003, the University Writing Program was created,

offering another opportunity for students to study

in small groups. The expectation of the program

is that students will become better writers and

more engaged in their education.

GW also launched select undergraduate programs

that encourage dialogue between students and professors—the

Dean’s Seminar Series in Columbian College,

the Dean’s Scholars in Globalization Program,

and the Women’s Leadership Program on the

Mount Vernon Campus.

Trachtenberg also recognized the importance of

athletics in building a university’s visibility

and school spirit. “The very best students

like to come to a school where there is good athletic

opportunity for them and good athletic performance

by the school’s teams,” he says. He

points to Duke and Stanford as universities that

boast both academic excellence and outstanding

athletic programs.

|

GW’s basketball

program flourished during Trachtenberg’s

tenure. Here, President Bill Clinton, daughter

Chelsea, and Chelsea’s friend join

President Trachtenberg, his wife, Francine,

and their son, Ben, in the Charles E. Smith

Athletic Center for the GW v. U. Mass game

on Feb. 4, 1995. GW defeated U. Mass., 78–75.

|

Enter men’s basketball coach Mike Jarvis.

Hired to coach the Colonials in 1990, he led GW

to three NCAA tournament appearances, including

the “Sweet Sixteen” in 1993. In the

2005-06 season, the men’s team went undefeated

in regular season A-10 play under leadership of

current coach Karl Hobbs. This season, longtime

women’s coach Joe McKeown, who has coached

his GW team to 13 NCAA appearances, was named

A-10 coach of the year for the fifth time after

leading his team to an undefeated A-10 regular

season. Once somewhat empty during home games,

GW’s Charles E. Smith Athletic Center now

vibrates during home games, with cheering fans

raising the roof.

At the same time, Trachtenberg helped to break

down financial barriers that might keep excellent

students out of GW. Since 1987, student financial

aid expenditures have risen from $14 million to

$118 million. To take the mystery out of tuition

planning, he created the Fixed-Tuition and Guaranteed

Institutional Financial Assistance Program in

2004. Incoming freshmen are guaranteed that their

tuition costs will remain the same for their full-time

undergraduate studies for up to five years. Likewise,

their minimum financial assistance is guaranteed

for up to 10 semesters. Their aid amount can increase

but not drop below the minimum they are granted

when they come to GW.

Everything that Makes

Washington Better Makes GW Better

The first year he was president of GW, Steve

Trachtenberg, who is Jewish, spent every other

Sunday at one of the city’s many churches.

It was a way to say that the University wasn’t

just in Washington, it was inexorably linked to

the city. GW is the largest private employer in

the District and many of its employees and alums

live in D.C. Trachtenberg has chaired the D.C.

Chamber of Commerce and served on the boards of

the Greater Washington Board of Trade, the Federal

City Council, and the Greater Washington Urban

League.

But Trachtenberg wanted to do more.

“I want people to know us as the University

that contributes more to Washington than any other

institution,” he has said.

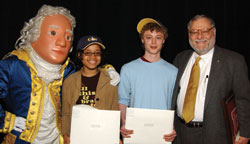

For 18 years,

the University has offered the “Stephen

Joel Trachtenberg Scholars” program,

which has provided more than 84 academically

talented D.C. Public High School seniors

with full, four-year scholarships covering

tuition, room and board, books, and fees.

GW’s total commitment since the inception

of the program is more than $12 million.

The scholarships, along with other grants

and work-study programs, make GW the largest

single post-secondary contributor of aid

to D.C. Public Schools for the last 13 years.

Julie Woodford

|

|

The Stephen Joel Trachtenberg Scholars program,

started in 1989, has awarded more than $13.5 million

to 93 of D.C. Public Schools’ best and brightest

graduates. They receive free tuition, books, fees,

and room and board. Originally called the 21st

Century Scholars Program, GW’s Board of

Trustees renamed the program in 1998 to honor

Trachtenberg and to celebrate his first decade

in office. The scholarships, along with other

grants and work-study programs, make GW the largest

single provider of post-high school aid to students

from the D.C. public schools. It’s a way

to keep potential community leaders close to home,

Trachtenberg believes.

Many of GW’s schools and colleges are involved

directly in supporting D.C. schools. The medical

center is involved in several health outreach

programs to District residents. Teams of undergraduates

and MBA candidates have assisted businesses in

D.C.’s economic development zones. In 2005-06,

more than 2,000 GW students and faculty and staff

members volunteered for more than 54,000 hours

with 66 community partners. GW also works with

more than 300 FRIENDS, a group of Foggy Bottom/West

End residents, to collaborate on neighborhood

issues.

Working to make Washington better is enlightened

self-interest, Trachtenberg believes. “It’s

the only way to enhance the institution and have

a chance at greatness. And it’s fun.”

He applauds the arrival of every new restaurant

or new museum. “It’s the multiplier

effect,” he says. Everything that makes

Washington better makes GW better.

He’s particularly pleased about Washington’s

new baseball team and city stadium. Trachtenberg

never forgave Walter O’Malley for moving

the Dodgers from his native Brooklyn to Los Angeles.

The Trachtenberg Touch

Trachtenberg credits his wife for making his

career possible. “I’m Francine’s

husband. I don’t mind being introduced that

way,” he says. In fact, the decision to

come to GW was a joint one. When it looked like

Trachtenberg was a serious candidate for the GW

presidency, Francine came with him to Washington

to see the school and the city. Her only other

visit to Washington had been a childhood tour

of the monuments.

Francine remembers her tour of the campus with

Ron Howard, a longtime GW administrator, who was

designated as her guide. Howard had been instructed

that Trachtenberg’s visit was confidential.

As they walked around GW, Howard was greeted by

many faculty members and students. He’d

stop to chat but never introduced his companion.

After several of these encounters, Francine told

Howard that she was uncomfortable being treated

like the woman who wasn’t there. They compromised—he

introduced her but told no one why she was there.

|

Francine Zorn Trachtenberg

has served the University in many areas.

President Trachtenberg credits her for making

his career possible. A scholar in her own

right, she has taught courses in the Department

of Fine Arts and Art History. In addition

to opening her home for countless events

for students, the faculty and staff, alumni,

and others, she has vigorously supported

the University’s art galleries and

artistic efforts, volunteered her time for

many GW and D.C. causes, and shared her

experiences by participating in the University’s

annual Women’s Leadership Conference.

|

Although her field of study was art history,

Francine takes no credit or blame for the bronze

hippopotamus that now graces the center of the

GW campus at H and 21st Streets. The family had

been on vacation and Francine left early to go

back to work. Trachtenberg announced that he had

sent her a gift. Then a delivery truck arrived

with two stone planters and the hippo. She instructed

the driver to unload the planters at the house

and told her husband to find another home for

the hippo.

Trachtenberg presented the bronze beast to the

University’s graduating class of 2000. Why

a hippopotamus? GW legend has it that hippos once

frolicked in the Potomac River to the delight

of George and Martha Washington, who watched them

from the porch at Mount Vernon. Hippos were credited

with bringing fertility to the plantation and

luck to anyone who could get close enough to touch

one of the beast’s noses.

While there are, in fact, no confirmed reports

of hippo sightings in the annals of American history,

the GW hippo often is pictured in the commemorative

photos families take of students on campus. It

has become an unofficial mascot with its own Web

site. Trachtenberg has received hippos as gifts

ever since.

It comes as no surprise to anyone who knows him

that Trachtenberg has decided to reinvent himself

as a University Professor of Public Service after

he leaves the GW presidency. He had already had

four professional lives—as an energy lawyer,

a Congressional aide cum education-policy wonk,

a doctoral candidate, and an assistant to the

U.S. Commissioner of Education—before he

arrived at Boston University as associate dean

in 1969.

He’ll teach an introductory course on public

policy. He also plans to write a book or two.

His first will be an “irreverent memoir”

of a university president, being published by

Simon & Schuster in the fall. Trachtenberg

has often said that university presidents give

up their first amendment rights. He is ready to

reclaim his. “Maybe I’m just beginning,”

he says.

What has now

become a popular, though unofficial, mascot

of GW, the bronze hippo statue arrived on

campus as a gift to the graduating class

of 2000 from President Trachtenberg. Legend

has it that hippos once frolicked in the

Potomac River to the delight of George and

Martha Washington, who watched them from

the porch at Mount Vernon. Hippos were credited

with bringing fertility to the plantation

and luck to anyone who could get close enough

to touch one of the animal’s noses.

Jessica McConnell

|

|

An ardent writer of letters, as evidenced in

Write Me a Letter! The Wit and Wisdom of Stephen

Joel Trachtenberg, published last year by

The New Yorker Co. and its Cartoon Bank, Trachtenberg

often can be found composing correspondence to

associates and friends. Five years ago, Trachtenberg

wrote to Julius Edelstein, senior chancellor emeritus

of the City University of New York on the occasion

of Edelstein’s 90th birthday:

“I have taken you as my role model and

recently told the chairman of my board that if

GW will have me... at 70, I plan to do what you

have done, namely, become a professor... do some

teaching and writing, and pretend that I am thinking.

“Francine claims it would be good for us

to take up dancing. Having made it all these years

without dancing, I’m not certain I agree.

...Also, I’d like to have a dog. I always

wanted a dog, but my mother would not permit a

dog when I was a boy since we lived in an apartment

in Brooklyn, and she alleged it would not be fair

to keep a dog cooped up. I remonstrated that the

apartment was good enough for me—to no avail.

I can report with authority that hamsters are

not a satisfactory alternative. Hamsters I had.

On reflection I could have done without them.”

Leslie Milk is the lifestyle editor of The

Washingtonian magazine.

|