By Jaime Ciavarra

Supreme Court expert Jeffrey Rosen recognizes the U.S. justices for their distinct constitutional philosophies and legal ideologies.

|

Legal journalist Jeffrey Rosen, who has been a professor at GW for a decade, says he considers a class successful when he has learned more than he has taught.

Claire Duggan

|

But he judges them by their quirks.

Over the course of American history, vivid personalities on the bench have been palpable: John Marshall shared his prized Madeira while chatting with colleagues. The undisciplined William Douglass scribbled his opinions on cocktail napkins. Antonin Scalia uses biting humor, at the expense of others, to evoke courtroom laughs.

The personality traits that may seem unimportant in other professions are integral to the most mysterious branch of government, where extraordinary legal minds, and strong egos, are transforming the nation’s laws, Rosen says.

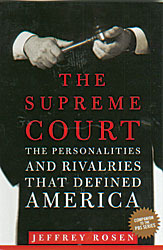

In his new book, The Supreme Court: The Personalities and Rivalries That Defined America (Times Books, 2007), journalist and GW Law School Professor Rosen expands on these quirks to argue that, more often than not, personality can be as important as judicial philosophy in determining success on the bench.

“I don’t think we want to put people on the couch and ask about their relationships with their mommies and daddies, but if we compare justices of similar philosophies, we find some are much more effective than others,” says Rosen, legal affairs editor of The New Republic. “Character and temperament play a role.”

As a journalist, Rosen began connecting the dots between temperament and legal philosophy while covering the Supreme Court in the 1990s, he says. His book, which is a companion to a four-hour series that aired on PBS in January and February, compares seven larger-than-life justices arguing that those who are pragmatic, and have a degree of likability and common sense, prove over time to be more effective than their heavy-handed, philosophically rigid colleagues.

The best example, he says, is John Marshall, a modest and convivial man who helped shape the court into the prestigious institution it is today. The best example, he says, is John Marshall, a modest and convivial man who helped shape the court into the prestigious institution it is today.

“[Marshall is] a hero to me—he’s such a paradigm case of the importance of temperament, because to him, temperament and philosophy merged,” Rosen says. “Temperament was what allowed him to bring ideological opponents together to room in the same boarding house, to drink his excellent Madeira, and in the process, to convince even the appointees of his arch rival, Thomas Jefferson, to join his vision of national power and independent courts.”

With a background in reporting, Rosen has learned to dissect the character traits of his subjects and analyze how those traits fit into the world around them, he says. The New York City native, who has written for The New York Times Magazine, The Atlantic Monthly, and as a staff writer at The New Yorker, is a natural storyteller. He expands on character, captures the eccentricities, and reveals the telltale details, colleagues say.

“Too often, legal historians approach the history of the court in a strangely ahistorical way. It’s almost as if context and personality didn’t matter. The court comes across as cerebral and independent—and the fiction that the court operates in some sort of impersonal bubble gets sustained,” says Sean Wilentz, professor of history at Princeton University and a contributing editor to The New Republic.

But The Supreme Court, Wilentz says, “brings to life the human dimensions of American lawmaking without simply reducing history to matters of personality and interest. Cerebral, independent humans remain, after all, human.”

By pairing justices (and one president) in the book, Rosen compares and contrasts the traits that led some to success and others to obscure failure. He focuses on John Marshall and Thomas Jefferson; Oliver Wendell Holmes and John Marshall Harlan; William O. Douglas and Hugo Black; and Antonin Scalia and William H. Rehnquist. Each is considered either an ideologue or a pragmatist, and each has helped shape the world we live in today, Rosen argues.

To bring these historical figures to life, Rosen sat before a fire at his Washington home and engrossed himself in judicial biographies. Researching the idiosyncrasies was key.

“Starting with constitutional philosophy can be daunting if you don’t have training in it,” he says. “But everyone can relate to personality.”

Rosen, who earned his bachelor’s degree from Harvard, jokes that he would never be a good lawyer—but he’s got the sharp eye for legal journalism. While pursuing a juris doctor at Yale University, Rosen interned at The New Republic, a magazine of politics and opinion headquartered in Washington, D.C. One of his first assignments, he says, was writing a staff editorial on the 1990 retirement of Supreme Court Justice William J. Brennan Jr. Only a few weeks into the internship, he quickly fell in love with the craft.

Rosen completed a clerkship on the D.C. Circuit after law school and, a short time later, The New Republic’s editor asked him to join the staff full time. Although he was only 28 years old and steeped in debt, Rosen saw the opportunity as a big break for his career. In time, Rosen became a steady contributor to other publications. In 2003, the Chicago Tribune named him one of the 10 best magazine journalists in America and, three years later, the Los Angeles Times called him “the nation’s most widely read and influential legal commentator.”

Supreme Court expert Kent Newmyer, a professor of law and history at the University of Connecticut, says Rosen has a knack for cutting to an issue’s core.

“He has a unique gift for making complicated material understandable…all while attending to scholarly accuracy and nuance,” Newmyer says.

Even with his writing success, Rosen knows he has more to contribute.

In 1997, Rosen was lured to the University by the wit and wisdom of GW Law School professors Ira “Chip” Lupu, Stephen Salzburg, and then-Dean Jack Friedenthal. From the start, it was a natural fit: Rosen says he always wanted to be a journalist or a professor. At GW, he could be both.

“GW has always been very supportive of the journalism,” Rosen explains about deciding to join the Law School’s team. “The faculty is engaged and supportive, the students are wonderful, it’s right in the middle of D.C. It couldn’t be better.”

In his office at Lisner Hall, there are few books—and no evidence that the professor of constitutional law and criminal procedure has a still-thriving reporting career. He does most of his writing at home. Rosen, in his even, soft tone of voice, says he tries to keep his positions as professor and journalist separate. But they undoubtedly intertwine.

During the spring semester, after the release of his new book, Rosen had students in his constitutional law seminar pick their own justices and expand on how their temperaments affected their tenure. The results delighted him, as students assessed everything from the desirability of John Roberts’ vision, to why Ruth Bader Ginsberg’s modesty was advantageous on the bench.

These in-depth discussions inspire Rosen both in the classroom and in his writing career, he says.

“I never think of a class as a success unless I’ve learned more than I’ve taught. I never think a paper is worth writing unless it teaches me something. Classroom discussions are exciting because they are always surprising,” he says. “The greatest lesson I’ve learned from students is how little I know.”

Like any lifelong learner, Rosen’s curiosity runs the gamut. He is an astute observer of constitutional history and the Supreme Court (his wife claims he has a “man crush” on John G. Roberts Jr.), but Rosen also finds himself fascinated by developments in neuroscience and security surveillance as they relate to policing and law. Two of his four books—The Unwanted Gaze and The Naked Crowd—focus on new threats to privacy in a technologically savvy and post-9/11 era. In The Most Democratic Branch, published in May 2006, Rosen analyzes how the Supreme Court can maintain its independence by following the mainstream of public opinion.

Now that he has completed his second book in two years, Rosen says he’s eager to relax and spend time with his wife, Christine, and his nearly 1-year-old twin sons, in between his teaching and writing schedule, of course.

When it comes to judging his own temperament as a professor at GW Law School, Rosen says he’s hopeful that, each day, he’s making positive progress.

“When I started teaching, I was nervous and gave very formal lectures about obscure bits of constitutional history law I had studied and was eager to impress on students,” he says.

Over the decade he has been at GW, he says he has learned to adjust his personality, relax, and listen more than he talks.

“I hope I’m getting better,” Rosen says. “And if I am, it’s because I’m trying to be open to learning.”

Book Smarts

Rosen has written three other books with a legal flair:

The Most Democratic Branch: How the Courts Serve America (Oxford University Press, 2006)—Rosen analyzes how the Supreme Court can maintain its independence by following the mainstream of public opinion.

The Naked Crowd: Reclaiming Security and Freedom in an Anxious Age (Random House, 2004)—In post-9/11 America, Rosen attempts to sketch a pathway toward a balance of security and privacy through legislation.

The Unwanted Gaze: The Destruction of Privacy in America (Random House, 2000)—Surprised by the personal violations sustained during the Monica Lewinsky scandal, Rosen explores the legal, technological, and cultural changes that have undermined our ability to control our privacy.

Rosen on Temperament and Chief Justice John G. Roberts Jr.

Last July, Rosen went to the Supreme Court to talk about temperament with John G. Roberts Jr., who had just completed his first term as chief justice of the United States. Under Roberts’ leadership during that first year, the court issued more consecutive unanimous opinions than at any other time in recent history, championing his vision that chief justices should help their colleagues speak with one voice. While discordant voices will always remain, Rosen says Roberts—so far—is getting it right.

“He encourages his colleagues to act less like law professors than members of a collegial court,” Rosen says. “He says that justices aren’t supposed to be like law professors, they are supposed to realize that they are to reach concrete and practical answers to legal questions and not write philosophical doctorates.”

Rosen maintains that it is too early to judge, especially after a notably divided term, but says Roberts seems to have many of the talents of the most successful and politically savvy chief justices.

“Much of his success is dependent on his colleagues and their willingness to support the collegial virtues of the court,” Rosen adds.

|

|