|

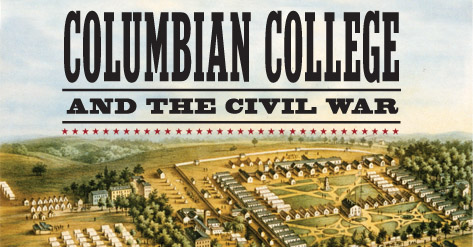

This lithographic print by Charles Magnus, which

is part of the University Archives collection,

depicts Columbian College and Carver Barracks

on College Hill in Washington, 1864.

By G. David Anderson

The American Civil War split Columbian

College as it did the nation. South of the Mason

Dixon Line, Washington was considered a Southern

city. When the conflict began, most students

left their classrooms to join the Southern forces,

while the faculty was split by opposing loyalties.

Because of its status as the nation’s capital

and its geographic location, the district soon

became the staging area for the Union. By order

of newly elected President Lincoln, the district

and the campus of Columbian College (original

name of The George Washington University) was

converted to barracks, accommodations for the

sick, troop quarters, and hospitals.

|

(above) George W. Samson was president of

Columbian College from 1859 to 1871. (below)

This photo, from the Matthew Brady collection

at the National Archives, shows the interior

of Carver Hospital.

(above) George W. Samson was president of

Columbian College from 1859 to 1871. (below)

This photo, from the Matthew Brady collection

at the National Archives, shows the interior

of Carver Hospital.

|

Chartered in 1821, Columbian College’s

first location was known as “College Hill.” This

46.5-acre tract of land extended north of Boundary

Street (now Florida Avenue) between 14th and

15th Streets. Purchased for $7,000, the land

was owned by John Holmead, who resided at Meridian

Hill. The campus was within walking distance

of the Capitol. The College’s central building

was a large structure for classes and boarding

that accommodated 100 students. Three smaller

buildings housed professors, the College president,

and the College steward. Classes began in January

1822 with 30 students registered for the first

term. In the years preceding the Civil War, approximately

300 students received their degrees from the

College.

In the mid-1800s, the city was growing and changing.

By 1853 Washington had installed gas lamps along

major streets. Washington’s first water

system was completed by 1859. By 1860 the population

had grown to 75,080.

The fifth president of Columbian College, George

Whitefield Samson, was elected in 1859. Samson

was pastor of the E Street Baptist Church in

Washington. He ended his tenure in 1871 as professor

of moral and intellectual philosophy. He had

the difficult duties of directing the College

during the years leading to, during, and after

the Civil War. With the aid of his colleagues

he kept the College open and worked to reestablish

the Law Department.

After the election of Abraham Lincoln, a known

anti-slavery proponent, the South seceded. In

January 1861 the South Carolina legislature called

a state convention and voted to leave the Union.

Virginia would secede in April of the same year

and by July the First Battle of Bull Run would

be fought just outside Washington. Samson reported

to the Board of Trustees on April 24, 1861, that

20 students out of 155 had left the College “owning

to the disturbed condition of the country.”

Curriculum at the College on the eve of the Civil

War was composed of a classical course for the

degree of Bachelor of Arts, a philosophical course

for a Bachelor of Philosophy, a select course

for master’s level study, a Medical Department

and hospital, and a successful Preparatory School.

The Preparatory School played a major role in

the life of the College, as it was a popular

place for students to prepare for admission to

Columbian or other colleges.

Courses at the College included Greek, Latin,

mathematics, modern languages, rhetoric, chemistry,

physics, botany, logic, intellectual philosophy,

astronomy, anatomy and physiology, ethical history,

political philosophy, and English literature.

Rhetorical exercises included compositions twice

and declamations once a month. There were two

literary societies. Both the Enosinian and the

Philophrenian Societies were formed by students.

Columbian College General Hospital,

with the main building of Columbian College

in the background and Union troops encamped

in the foreground. The original photo is

part of the Ordway Collection at the Library

of Congress.

|

|

Fees for students were $10 for admission, $55

for tuition, $20 for room rent with servant’s

attendance (slaves were not permitted), $15

for fuel, $10 for use of furniture (if provided

by the college); and $10 for washing at 50

cents per dozen. Of interest was the acceptance

by the College, as the war began, of Virginia

money for some payments.

The Preparatory Department had a principal and

five assistant teachers. The Preparatory Department

occupied a building on the College premises.

The students were under the supervision of the

faculty and subject to all regulations of the

College in regard to discipline. In the 1860-61

academic year there were 69 students.

In 1860 Columbian College students helped in

the construction of a gymnasium on College Hill.

By 1860 one fraternity, the Washington Rho chapter

of Sigma Alpha Epsilon, was active at Columbian

College. SAE was founded in 1856 at the University

of Alabama in Tuscaloosa by Noble Leslie DeVotie.

His younger brother, Jewett DeVotie, organized

the 10th chapter of SAE at Columbian College.

Most “brothers” of SAE fought for

the South. Only at Columbian College and Kentucky

did SAE members fight for the Union. Washington

Rho at Columbian College was the only chapter

to survive the Civil War. Other chapters were

re-established with the end of the war.

With the secession and the start of war the city

was becoming an armed camp. One of the few public

improvements was the installation of the equestrian

statue of George Washington at Washington Circle

(1860) in the area that would be the future home

of The George Washington University.

The citizens of the district were split in their

loyalty to North and South. The city, for the

most part, was undefended and was certainly not

prepared to house all the troops to come or respond

to the multiple wounded. Because of its location,

the district became the principle receiving point

for wounded and sick and the gateway to invasion

in the South.

|

(left) Columbian College professor

Albert Freeman Africanus King was

one of several physicians who tended

to President Lincoln immediately

after he was shot. (right) Robert

King Stone was Lincoln’s

personal physician.

|

The Union forces commandeered all churches, public

buildings, large private homes, and academic

institutions. In addition to barracks, and governmental

and military operations, the district essentially

became one large hospital.

The Army commandeered

the College Hill campus and the hospital downtown.

Despite reduced enrollment, professors continued

to hold classes, often in their homes. From 1861

to 1865 the College had 194 registered students.

The Preparatory School had 357 students. The

medical graduates served

during the war—46 for the Union, 24 for

the South. Many faculty members also served,

including Dr. John G. F. Holston, professor of

surgery, and Dr. Joseph H. Warren, professor

of anatomy.

The Army moved onto the campus, often occupying

areas without permission. The fence surrounding

the campus was partially destroyed by solders

of the Third Maine Regiment of Volunteers. The

Army reimbursed the College for the damages.

The government also agreed to rent the campus

for $350 per month. This fee was later reduced

to $250. In addition, by October 1862 the steward’s

house was rented and 16 acres of the campus were

occupied for barracks. The College’s association

with the army was not a pleasant one. The College

water pump was used by 3,000 men and damage to

College facilities mounted as the war continued.

Within the campus the Columbian College and Carver

general hospitals were established. Carver had

1,300 beds and Columbian College 844. During

the war these hospitals were visited by President

Lincoln. Walt Whitman also devoted time to the

patients at Carver Hospital.

The Washington Infirmary at Judiciary Square

was a teaching hospital, home to the Medical

Department since the 1840s, and a meeting place

for the Medical Society of the District of Columbia.

The infirmary enjoyed several prosperous years,

but with the beginning of the American Civil

War, the school entered a difficult era. The

infirmary was the only available hospital in

the district. In April 1861 it was requisitioned

for military use.

As the city was mostly undefended, the Sixth

Massachusetts Regiment was ordered to move to

Washington. While marching through Baltimore,

the unit was attacked by hostile mobs of Southern

loyalists. Many of the wounded were moved to

the Washington Infirmary. After the First Battle

at Bull Run the number of wounded increased.

The Southern threat to the city was very real.

Enemy gun sites could be seen across the Potomac.

It was essential that Washington be protected.

As a result Arlington, Alexandria, and surrounding

areas in Virginia were captured and occupied

by Union forces. Afterwards a series of forts

were established, surrounding the city.

The Washington Infirmary would survive the war

for only six months. On Nov. 4, 1861, a fire

completely destroyed the hospital and the offices

of the medical school. The

Washington Star reported

in 1861 that more than 100 patients were removed

from the building (one patient died). By the

time the fire engines arrived the facility was

destroyed. So ended GW’s first established

teaching hospital.

Despite the chaos of the war, the medical college

regrouped and in 1863 reopened in the Constitution

Office on E Street between 12th and 13th Streets,

N.W. Because of the depletion of students and

faculty members, lectures at the medical school

were suspended between 1863 and 1865.

This illustration from the Nov. 23,

1861, Harper’s Weekly shows the burning

of the Washington Infirmary on Nov. 4,

1861. The infirmary was home of Columbian

College’s clinical hospital and medical

school. The fire completely destroyed the

hospital and the medical school offices.

Only one of 100 patients is reported to

have died in the fire. The rest escaped

or were rescued.

In the 1840s, the Department of Medicine

had moved into the infirmary, which was

formerly the old jail at Judiciary Square.

It was then that it became known as the

Washington Infirmary and the National Medical

College, one of the nation’s first

teaching hospitals.

|

|

Beginning a long tradition of GW service to

presidents, medical faculty member Dr. A.Y.P.

Garnett left Washington to become Jefferson Davis’ personal

physician, while faculty member Dr. Robert

King Stone remained to serve Abraham Lincoln.

Garnett knew many Washington officials. In order

to go to Virginia, Garnett had to ask permission

and obtain a passport from the Secretary of War

to travel to the South. He later became physician

to the Lee family and Jefferson Davis. In charge

of Richmond Hospitals, Garnett returned to

his practice in Washington at the end of the

war.

At approximately 10:15 p.m. on April 14, 1865,

Lincoln was shot in the back of the head by John

Wilkes Booth. After being taken from Ford’s

Theater, Lincoln was attended by several physicians.

Among them were Columbian College professors

Dr. John F. May and Dr. A.F.A. King

At Lincoln’s bedside surgeons Joseph K.

Barnes and Robert King Stone found the wound

to be mortal.

At the end of the Civil War the army and other

government authorities made slight repairs to

the main College building, the Steward’s

house, and the engine room, which heated both

buildings. They declined to repair the boiler

and fixtures or repair the pipes damaged by overuse

and improper drainage. In 1868 President Samson

requested the Board of Trustees allocate $2,500

for repairs to the Steward’s house, occupied

by the principal of the Preparatory School, and

the library, which was relocated to the upper

room of the building formerly occupied by the

Preparatory Department.

In 1865 the Law School was re-established.

From 1865 to 1867 the medical school shared

space in the Columbian College Law Building

on 5th Street between D and E Streets, N.W.

The Law building also served as a church

on Sundays.

The hospital and medical school moved to 1335

H Street in 1868. The new building, which previously

housed the Army Medical Museum’s specimens,

was donated by W.W. Corcoran, philanthropist

and president of the Board of Trustees from 1869

to 1888. Medical school and law school lectures

were held in the late afternoon or evening to

accommodate federal workers.

By 1870 Washington’s population reached

109,000. Washington was a growing community.

By 1871 the president’s annual report listed

a total of 376 students. After the war and in

spite of the conflict that split the College

and the nation, the College was recording an “unusually

large number of applications, particularly from

the Southern States.” Even with the neglected

condition of its campus, Columbian College resumed

its role as a key institution of higher learning

in the District of Columbia.

G. David Anderson is the University Archivist

and Historian. Information for the article came

from a variety of sources, among them the books,

records, and visual materials found in the University

Archives. Additional sources include: the books

and writings of Elmer Louis Kayser, the University’s

first official historian; Capital Medicine:

A Tradition of Excellence by Nancy B. Paull; City

of Magnificent Intentions by Keith Melder;

and Washington At Home, edited by Kathryn

Schneider Smith. Also, information was pulled

from the Ford’s Theater National Information Site.

|