|

They are as American

as baseball and apple pie: The U.S. film and music industries

lead entertainment trends throughout the world and remain

the benchmark to which other countries’ efforts aspire.

Along with other copyright industries, they contribute

billions of dollars to the U.S. economy, outperforming

other sectors and playing an increasingly leading role

in the growth of exports.

Two GW alumni lead

these industries in top positions. While there may be nothing

more “American”

than Hollywood, there’s nothing more “GW” than

a prime lobbying job—especially in Washington, where

one of these men leads his organization just a few blocks

from campus.

They both have one other common bond.

Their industries have been threatened—by the same technology

that also spreads their good work all over the world at lightning

speed. Both men discuss that threat here, along with how they

ended up in the middle of this fight for their industries’ lives.

Not in Kansas Anymore

By Tom Nugent

Former

Agriculture secretary turned Motion Picture Association

of America President Dan Glickman, JD ’69, relishes

the challenges

ahead.

When the news broke last summer that Dan

Glickman had been tapped to replace the legendary Jack Valenti

as the next Hollywood ambassador to the U.S. government, more

than a few movie industry observers expressed feelings of

overwhelming befuddlement.

With George W. Bush in the White House and

strongly favored to remain there, and with the Republicans

firmly in command of Congress for the foreseeable future,

why would the moguls of the Silver Screen choose a former

Democratic congressman from Kansas—and a former secretary

of Agriculture, of all things—to be their next Capitol

Hill point-man?

An unlikely sounding scenario? You bet.

Before deciding to retire last year at age 82, the impeccably

groomed and fiercely charismatic Valenti had spent 38 years

as one of the nation’s most effective lobbyists. Secure

in the power of his trademark smile, Valenti by 2004 had become

a Washington institution.

Before departing the scene, however, the

lobbying legend would apply his persuasive power to one final

task: choosing his replacement. Who would win this coveted

job as the high-powered voice of the motion picture industry?

May I have the envelope, please? And the

winner is … the longtime farm-state legislator from Wichita:

Dan Glickman!

Go figure.

Dan Glickman stands in the Arterberry

farm outside Newcastle, Okla., in July 1998 during a

tour to see the effects of that summer’s drought.

Glickman served as Agriculture secretary from 1995 to

2001.

J. Pat Carter, AP/WWP

|

At first glance, most veteran Washington

observers were totally flummoxed by the choice. Let’s

face it: Unlike Valenti, Glickman does not number dazzling

personal charisma among his political assets. A smallish,

balding man who tends to wear dark, square-cut suits and narrow,

earnest ties, the 60-year-old Kansan is quick to concede that

the decision to make him the next president and CEO of the

hugely influential MPAA “probably startled a few people

in Washington, at least when they first heard about it.”

Glickman himself often sounds surprised

to have landed his new high-profile job as the Hollywood PR

Czar. “A few weeks after I was chosen to head the association,”

he told GW Magazine in a recent interview, “the

editors at The New York Times decided to run a profile

of me.

“When the piece appeared a few days

later, I noticed that on the left-hand side of the page was

a big picture of Jack Valenti with [famed Italian actress]

Sophia Loren at the Cannes Film Festival. On the right-hand

side, they ran a photo of me and [87-year-old] Senator Robert

Byrd going through some cornfield in West Virginia.

“I took one look at that layout, and

I realized that I’m never going to be Jack Valenti. Hey,

Jack is Jack, and I’m me. I’ve got heartland roots,

and I hope they’ll always be part of me. And I’m

also convinced that those roots are going to help me on this

new job.”

While touting his heartland credentials—“I

represented the reddest of the red states, and the movie people

are well aware of that”—Glickman also points to

his track record during nearly six years (1995-2001) in the

top job at the Department of Agriculture. “I had to manage

100,000 employees and a $70 billion annual budget on that

job, and I like to think I met the challenge,” he says.

After spending the past six months answering

the same basic question from reporters—“Why did

Hollywood pick you?”—Glickman has assembled a list

of reasons why his selection made very good sense, at least

from Hollywood’s point of view.

Valenti is one of these reasons. Valenti

hasn’t made this point public, but everyone in the industry

understands that Valenti had total veto power over the selection

and that he leaned toward Glickman because of his political

and international trade experience (especially with China).

It didn’t hurt, either, that former Lyndon B. Johnson

aide Valenti was—like Glickman—a passionate Democrat.

During 18 years in the House of Representatives,

Glickman became known for an ability to “work both sides

of the aisle” to gain nonpartisan support to push important

legislation through the pipeline. He also knows U.S. copyright

law inside-out and the Byzantine process that will be required

to get new anti-piracy laws through Congress. While serving

for many years on the House Judiciary Committee, he specialized

in technical and intellectual property ownership issues. His

legal skills will aide the MPAA’s number-one requirement

in 2005: finding a way to stop the movie pirates, who are

stealing an estimated $3 billion from the big studios each

year, Glickman says, by copying VHS tapes and DVDs, and downloading

and file sharing movies at an alarming pace.

Glickman also has personal links to the

movie industry. His son, Jonathan, is a Hollywood producer,

with comedies such as Shanghai Knights and the Rush

Hour series

to his credit. In addition, Glickman’s wife, Rhoda, was,

for 15 years, the director of the Congressional Arts Caucus,

where she coordinated Capitol Hill movie screenings hosted

by Valenti.

Lastly, Glickman says, he loves to go to

the movies. He isn’t lying when he brags about attending

“at least 50 new movies each year.”

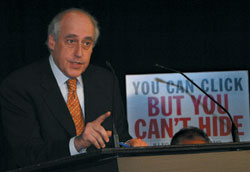

In November in Los Angeles, MPAA

President Dan Glickman warns that his industry plans

to sue people who illegally distribute movies online.

Stefano Paltera, AP/WWP

|

One veteran Washington insider who says

he wasn’t at all surprised by Glickman’s ascension

last July to his $1.5 million-a-year MPAA post is Sen. Pat

Roberts (R.-Kan.). After working closely with Glickman on

farm legislation for many years and watching him run the Department

of Agriculture with a “firm, steady hand,” Roberts

says he was quick to give the former Clinton cabinet member

“a very positive reference” when the MPAA recruiters

called him for a candid assessment of Glickman’s administrative

and political skills.

“I don’t always agree with Dan,

but I gave him a great reference, anyway,” joked the

longtime Republican. “I told them that even though he’s

a Democrat, I recommend him highly. It used to be said that

[running] Agriculture is the toughest job in Washington—and

I told the headhunter that if Dan could handle that job, I

don’t think he’ll get ambushed at the MPAA.

“Of course, I suspect he’ll have

to face some very big egos in the movie industry, but I’m

sure his background in politics has prepared him for that.”

Another well-connected Washington politico—eight-term

Rep. Richard Neal (D.-Mass.), a high-ranking member of the

House Ways and Means Committee, which could have a significant

role in economic decisions affecting the movie industry in

the years ahead—points to Glickman’s easygoing leadership

style. “Dan was an extremely intelligent legislator and

a savvy strategist,” Neal says, “but he’s also

blessed with a good sense of humor. He doesn’t take himself

all that seriously—which makes him very good at building

coalitions and achieving consensus.”

As a young boy in Wichita, Glickman couldn’t

get enough of the movies—and of “that delicious,

aromatic popcorn they sold in the lobby of our neighborhood

theater,” he says.

The movie house was the Crest, located six

blocks from Glick-man’s boyhood home. Glickman says he

rarely missed a Saturday afternoon in “that magical setting,

where dreams came alive on the screen and you could escape

from the everyday world for a couple of hours, just by purchasing

a 25-cent ticket.

“I must have caught all 26 of the Flash

Gordon serials, along with every one of the old Atom

Squad adventures. I know I’m dating myself a little

bit here, but the fact is that as a kid in Kansas, I really

loved the movies. Growing up in the 1950s, in a place like

Wichita … you have to remember that TV wasn’t as

big a part of our lives as it is now. For us, going to that

movie theater was a big, big thing.

“In our family, there was another interesting

twist, when it came to the movies. My dad, Milton—he

absolutely loved movie popcorn. They cooked it in coconut

oil, or maybe it was palm oil, back in those days. Anyway,

he was sure that it tasted better as a result—and almost

every night, he’d send one of us three kids down to the

theater for a box of that popcorn. They all knew the Glickman

kids at the Crest Theater, let me tell you.”

|

Glickman also remembers his time at GW fondly.

“I wasn’t that great of a law student. I did okay,

I guess, but nothing special. [Actually, he graduated with

honors.] And every once in a while, my shortcomings as a student

would become extremely obvious—especially during the

criminal law course I took with Professor James Starrs. During

my time, he was a lot like that law professor in the movie,

The Paper Chase. He was a terrific teacher,” Glickman

says. “I also learned a lot about civil procedure from

Professor Jerome Barron, who went on to become dean of the

Law School.”

These days, after six months on the job

at MPAA, Glickman says he’s having more fun than he ever

expected.

“It’s true that I face a lot more

stress here than I did at the Department of Agriculture,”

he points out, “even though I’ve only got about

250 employees and a budget in the tens of millions [of dollars],

instead of $70 billion.

“One of the reasons for the higher

stress is that here I’ve got many, many bosses [the movie

producers], whereas at the USDA, I basically had one boss,

the President of the United States. Of course, the MPAA is

also facing some tough survival issues, such as the piracy

problem, along with many difficult technological and international

trade issues. This job is extremely challenging on a lot of

fronts, which is the main reason I like it so much.”

Another pleasant job perk, Glickman says,

is the opportunity to rub shoulders with megawatt movie stars

now and then.

So what’s it like to spend an occasional

hour or two in the company of folks like Jack Nicholson, Brad

Pitt, and Julia Roberts? Does the former Kansas farm legislator

ever feel shy or intimidated around these world-class celebrities?

“Oh, I don’t think so,” Glickman

chuckles. “You know, I’ve lived long enough to know

that you just can’t let yourself be intimidated by people,

including movie stars. In my line of work, what you end up

learning is that most people are pretty much the same—some

are more beautiful than others, that’s all.

“I’m very respectful around the

stars but not intimidated. I’m smart enough to know that

if Brad Pitt walks in the door and Senator [Arlen] Specter

or Senator [Orrin] Hatch also walks in, I have to show as

much or more respect to the Hatches and Specters of the world

as I do to Brad Pitt.”

The Music Man

By Tom Nugent

Neil Portnow, BA ’71, knows

a thing or two about the music biz.

For Recording Academy President Neil Portnow,

the long climb to the top began with a GW bullhorn.

He remembers the moment vividly: He picked

up the bullhorn and leaned out the third-floor window of Maury

Hall at 19th and G Streets on the campus of GW. Twenty feet

below, a surging mob of angry students chanted again and again:

“One, two three, four … We don’t want your

dirty war!”

It happened on a crisp fall afternoon in

1969, when the president of the GW Student Association—a

charismatic senior named Neil Portnow—decided it was

time to “get negotiations started, before a complete

riot broke out” at Maury, then a frequent target of anti-Vietnam

War demonstrators.

Without hesitating, Portnow lifted the hastily

commandeered bullhorn to his lips. “All right, everybody:

We need to think seriously about our actions before somebody

gets injured. I want to tell you that I’ve spent the

past two hours talking with the administration, and they are

ready to negotiate!”

Neil Portnow addresses the audience

and millions of TV viewers during the GRAMMY Awards

in February.

Courtesy

of The Recording Academy, Photo by Wireimage © 2005 |

On that breezy autumn afternoon, Neil Portnow

spent nearly an hour in the window of Maury Hall, doing his

best to broker some crucially important negotiations between

outraged student demonstrators and administrators who were

doing their best to keep their university functioning at the

height of the Vietnam War.

“Attending GW in the late 1960s and

early 1970s was an amazing experience,” says the 56-year-old

Portnow, today the president of the National Academy of Recording

Arts & Sciences Inc. (known as The Recording Academy).

“From one hour to the next, you didn’t know if the

school would even remain open for classes. Washington was

full of anti-war activists, and life on campus seemed increasingly

chaotic.

“Of course my own personal politics

were left of center. I’d been in several peace marches,

myself. At the time, however, I was serving as student body

president, which meant I had a responsibility to keep the

lines of communication open to the University administration.

In some ways, I saw myself as an undergrad version of Henry

Kissinger—a negotiator whose task was to try and get

everybody to cool the rhetoric and stand down a notch. At

the same time, though, I was also urging the administration

not to overreact by bringing in the D.C. police and the tear

gas.

“That standoff in the window lasted

quite a while—but in the end, we managed to get the negotiations

started, and order was eventually restored.”

Pausing for a moment, The Recording Academy

president chuckles with light-hearted nostalgia. “Looking

back on that showdown at Maury Hall, I guess you could say

it was where I first began to work on my skills as a negotiator

in a crisis situation.”

Since then, he has spent more than 30 years

in the music business—as a performer, as a marketer,

and as an administrator. “I do think the ability to negotiate

between different groups is the key to any success I’ve

been able to achieve,” he says.

As a hugely successful record company executive—think

Zomba, Arista, EMI, RCA, and Twentieth-Century Fox—Portnow

long ago proved he had the magic touch required for selling

millions of songs by such superstars as Whitney Houston, Britney

Spears, the Backstreet Boys, and R. Kelly.

These days, just about everybody in the

music business knows that Portnow has an extraordinary ability

to negotiate between the big-time music creators (including

such over-the-top writer-producers as Max Martin, Robert John

“Mutt” Lange and Teddy Riley) and the tens of millions

of worldwide music consumers who pay the bills.

Indeed, The Recording Academy acknowledged

Portnow’s obvious talents as a marketer and manager when

it tapped him in 2002 to replace the legendary C. Michael

Greene, who had just departed the 18,000-member Academy after

14 years as its often outspoken and controversial chief executive.

Neil Portnow stands in the middle

of a star-packed linuep after reading nominations for

the 2003 GRAMMY Awards at New York’s Madison Square

Garden. (from left:) Ashanti, Avril Lavigne, Nelly,

John Mayer, Neil Portnow, Cyndi Lauper, Kenny Chesney,

Jimmy “Jam” Harris, and Justin Timberlake.

Richard Drew, AP/WWP

|

Having established an enviable track record

as a high-voltage marketer and administrator at half a dozen

major record companies, Portnow was an obvious choice for

the high-six-figure-a-year top job at the Academy, according

to industry insiders. “Neil comes to us with superb credentials,”

said Academy Board Chairman Garth Fundis soon after the GW

grad’s ascension to the corner office, “and he has

a unique skill set that perfectly matches what we were looking

for in a new president.”

A bit more than two years after his selection,

Portnow continues to prove that the industry execs who backed

his candidacy got it right.

Under his steady hand, the Grammy® Awards

music special—by far the biggest enterprise launched

by the Academy each year—has improved dramatically, according

to most of the national critics. Ask key industry figures

such as RCA Label Group Chairman Joe Galante to evaluate the

yearly shows, and many will tell you that last February’s

extravaganza (featuring the irrepressible Queen Latifah as

emcee and other stars such as Green Day, Kanye West, and Alicia

Keys) may have been the best-produced Grammy spectacle in

the entire 47-year history of the event.

Says the Nashville-based Galante, “Neil

has done a tremendous job of reaching out to people. He’s

gregarious, and he really enjoys telling the world about the

artists the Academy represents. He also loves to get out there

in the music community and ask people about their issues—because

he wants to learn all he can about every aspect of our industry.”

Portnow’s influence isn’t limited

to the big recording studios where writers and performers

spin their magic. Ask California congresswoman Mary Bono (she’s

from Palm Springs, and she knows a thing or two about music)

to describe Portnow’s performance as a member of her

recently formed Recording Arts and Sciences Congressional

Caucus and the well-known widow of former singing star Sonny

Bono won’t hesitate.

“Neil is a powerful advocate for musicians

and writers in America,” says Bono, who co-chairs the

caucus and passionately supports its mission to protect the

rights of musicians, songwriters and singers from “copyright

pirates who illegally download music from the Internet.”

“Neil does a great job on that issue—and he also

understands the complexities of the [Capitol] Hill,”

she says. “In his job as Academy president, he has to

negotiate between two worlds that are often at odds: Hollywood

and Washington. But he does it very well. His communications

skills seem to be natural—he’s charismatic and also

extremely knowledgeable.

“Thanks in large part to Neil’s

energy and dedication, we are beginning to educate the American

public about the vital importance of respecting copyrights

and intellectual property rights in this country.”

Most people in the music business know Portnow

for his skill as a creative executive, marketer, and negotiator.

But only a few of the performers he represents know that the

Academy president, himself, once dreamed of topping the charts

as a bass player and guitarist.

For Portnow, who grew up in the middle-class

community of Great Neck on New York’s Long Island, the

musical passion began in earnest one night in the mid-1950s,

when a brand-new phenom named Elvis sang a tune called “Hound

Dog” on the Ed Sullivan TV show.

|

Courtesy of The Recording Academy,

Photo by Wireimage © 2005

|

“I was raised in a family that had

a great love of music,” he says. “As soon as I was

old enough as a child, my parents started taking me to performances

by the Great Neck Symphony Orchestra on Sunday nights. And

at first, it was: ‘Aw, mom—do I have to go?’

But pretty soon I started getting excited about music, all

kinds of music. And about the same time, I caught one of those

Ed Sullivan Shows with Elvis, and that did it for me. ‘Hound

Dog’! And I started bugging my parents for a guitar.

I was eight years old, and I was already asking for guitar

lessons.

“I got very interested in jazz guitar—performers

like Wes Montgomery and Charlie Christian and Joe Pass. And

at the age of 12, I formed my own band at school. I played

in bands all the way through high school and college—including

a long stint for The Savages, a group I founded and managed

for several years.”

By the time he hit GW, however, Portnow

had already begun to ask himself if he belonged onstage as

a performer or backstage as a marketer of other performers.

“I woke up one day and realized that I was torn between

my music and my interest in politics and business. By then

I was involved in booking concerts for bands at GW, and I’d

already been elected student body president. I wanted very

much to run for political office and save the world! And the

practical side of me felt that a musical career was going

to be less likely, so I better have something solid that I

could really get into that was a little more, ‘legitimate!’”

What followed, of course, was a remarkable

run as one of the most successful music executives in the

annals of contemporary music. By the late 1990s, the fleet-footed

Portnow had risen to senior vice president of operations for

the giant Zomba Group on the West Coast, where he also spent

a lot of time as a volunteer leader for The Recording Academy.

“When I look back at the early years,”

he says, “I realize that the ability to negotiate between

different groups has undoubtedly been the key element in my

professional life, and that it all got started at GW.”

These days, his toughest challenge can be

defined in a single word: “piracy.”

As the point man for the 18,000 music writers

and performers in his organization, it’s his responsibility

to lead the battle—in Congress and elsewhere—to

prevent further erosion of music copyrights and intellectual

property rights in this country, due to the high-tech banditry

that he says is now occurring daily on the Internet.

“Right now, the Academy is doing its

best to educate people—and especially younger people—about

the importance of respecting copyrights, and that isn’t

easy. One of the problems has been that it’s quite easy

for the kids to go out and buy high-tech equipment that allows

them to do the [illegal] downloading and file sharing.

“We’re trying to change behavior

that’s been established in some young people for a while,

and we’re hoping to educate for the future. As for the

lawsuits recently filed… well, once in a while, maybe,

you take out the stick and somebody gets a little slap on

the behind. Unfortunately, that’s sometimes a necessary

part of changing behaviors. The Academy’s Rule is to

use education as a tool for change.”

Is Portnow confident that the pirates can

be stopped, and that the future of commercial music in America

remains as bright as ever?

“You bet,” he says. “I’m

a real optimist when it comes to thinking about our industry’s

future. Let’s face it: Good music is more available today

than ever before, and millions of consumers worldwide are

enjoying it on a scale never seen before.

“As an industry, we have to sit down

and figure out a new business model—and we will. I see

some very good days ahead for music-lovers and music-creators

alike, well into the future.”

A Shared Crusade

When Neil Portnow took the stage at the

Grammy awards this year to deliver his annual speech as president

of The Recording Academy, he was doing his part to fight music

piracy. As part of a promotion for a star-studded tsunami

relief song, he touted the availability of the song on iTunes,

a legal venue for downloading music on the Internet.

While Portnow’s industry was the first

to face the threats that piracy, particularly the newer threat

posed by illegal downloading from the Internet, Dan Glickman’s

motion picture industry shares the same challenge. For both

men, the issue is at the forefront of survival of the businesses

they represent.

“In the past, copyright piracy has

been a much bigger problem for the music industry than for

Hollywood,” Glickman said about his industry in December,

just after announcing that the Motion Picture Association

of America had just filed dozens of lawsuits against Internet

thieves who allegedly steal Hollywood movies and then share

them online. “But with the rapid development of movie-replicating

and file-sharing technology, all of that is about to change.

This is the biggest threat now facing the

film industry, by far, he says. It’s a dagger at the

heart of the movie business, and if we’re going to defend

ourselves against it, we have to put together the right combination

of aggressive legal action and education.”

Both men are watching an impending decision

from the Supreme Court, which in December agreed to review

a key case that likely will determine whether such Internet-based

file-sharing enables as “Grokster” and “Morpheus”

will be held financially responsible for losses, if their

services are found to have contributed to movie piracy. At

this magazine’s press time, the Court was scheduled to

review the case in late March.

A positive outcome from the Supreme Court

could help Glickman’s industry tremendously. “The

average movie today costs $103 million to make, and six out

of 10 of them don’t make that money back. Making movies

has become incredibly expensive—and that’s why preventing

piracy has become so crucial.”

On the music side, much has changed since

services like Napster first came online a few years ago, offering

Internet surfers free access to music downloads. These days,

Napster is a revamped, fee-based service (as is the Mac-based

iTunes), that allows users to buy song downloads for 99 cents

and albums for $9.95. For its part, GW, as part of a select

group of universities, is participating in a pilot program

for the 2004-05 academic year that allows 7,100 residence

hall students to have complimentary subscriptions to Napster.

GW also monitors network traffic to enforce legal downloading

policies.

It was the music industry that first began

the barrage of lawsuits within the past two years aimed to

curb Internet piracy. “The lawsuits sent America a powerful

message: If you are file sharing copyright-protected music,

you are breaking the law,” says Mitch Bainwol, chairman

of the Recording Industry Association of America (which represents

the record companies), who is Portnow’s Washington counterpart

in the crusade against illegal downloading.

Bainwol says he’s glad to have Portnow

as a partner in his battle against Internet piracy. “Neil

is a very thoughtful—and persuasive—ally in the

ongoing effort to educate America about this issue,”

he says. “As an advocate for musicians everywhere, he

has been a powerful voice in support of the copyright and

intellectual property rights that are guaranteed to all of

us by the Consitution.”

—Heather O. Milke and Tom Nugent

Back to top |

Spring/Summer 2005 Table of Contents

|