Akos Vertes’ latest project is generating enthusiasm from groups as diverse as undergraduate students and major foundations. Vertes, professor of chemistry and co-director of GW’s Institute for Proteomics Technology and Applications, is the principal investigator charged with developing a new in vivo “protein microscope” to enable researchers for the first time to view how proteins interact in living tissue. Vertes is collaborating with Mark Reeves, associate professor of physics, Fatah Kashanchi, associate professor of biochemistry, and Eric Hoffman, the James A. Clark Professor of Pediatrics and Biochemistry. The microscope is expected to enable researchers to identify protein targets that may advance the treatment of neurodegenerative diseases such as Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis (Lou Gehrig’s disease) and spinal muscular atrophy. The project also may have implications for research on a multitude of other diseases, including HIV and cancer. The W.M. Keck Foundation awarded a $1.5 million grant to support this research at the IPTA, which is an interdisciplinary research collaborative among the departments of chemistry, biology, and physics in the Columbian College of Arts and Sciences; the departments of biochemistry and molecular biology and of pharmacology in the School of Medicine and Health Sciences; and the computer science department in the School of Engineering and Applied Science. “This is a very prestigious grant,” Vertes says. The research has two primary phases. First, researchers will create an in vivo “protein microscope” that provides images of protein distributions in living cells and tissues by combining a high-tech mass spectrometer with a special optical microscope. Second, in collaboration with the Children’s National Medical Center, researchers will explore protein distributions in and around the neuromuscular junction in unprecedented detail. The microscope is being designed to produce images with resolutions of 100 nanometers or one-tenth of a micron—about two-thousandths of the thickness of a human hair. “Our current limitation is three microns. We hope to do 30 times better, which may not sound like a big deal, but this is the length scale where the real action starts,” Vertes says. “We will be able to see the distribution of various proteins at the surface of the cell.” Vertes cautions that the project is still in the design phase, but he doesn’t hide his hope. “We have the coalescence of resources, recognition, and scientific excitement in one package,” he says. “This is a high-risk, high-return project with very broad applications. We’re on a technological tour de force.” —Rachel Muir

Research Takes Center Stage With New LeadershipAs GW strives to keep pace with its ever-expanding research enterprise, the University has created one new management position and filled a second to guide University efforts.

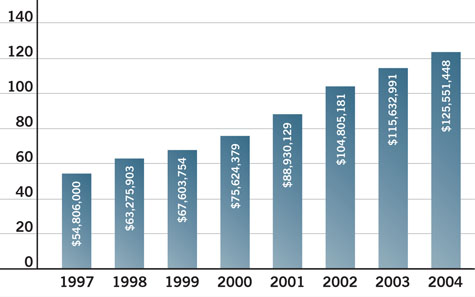

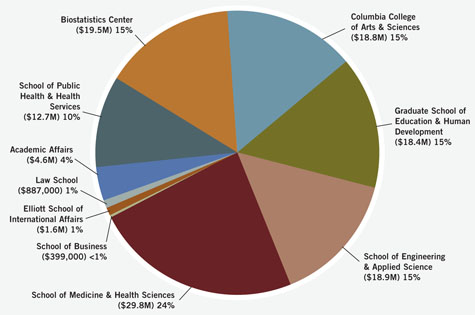

Elliot Hirshman, chair of psychology, has stepped forward to play a leading role in the process as the University’s interim chief research officer. A cognitive neuroscientist, Hirshman came to GW in 2002 from the University of Colorado at Denver, where he served as chair of psychology. Earlier in his career, he spent more than a decade at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, rising steadily through the ranks to professor of psychology and special assistant to the provost. The author of more than 100 peer-reviewed journal articles, he specializes in the cognitive and biological basis of human memory. As GW’s first chief research officer, Hirshman is responsible for overseeing the University’s extensive research infrastructure. “The research enterprise at GW has grown dramatically over the last decade, and it is, therefore, critical to have a single person who is focused solely on and has broad accountability for research issues,” he says. “My top priority is to advance research at GW. This involves facilitating the critical research needs of our investigators while ensuring that we are in compliance with our sponsor and governmental regulations.” According to Hirshman, research at GW has expanded in every school and college in recent years. “We have contracts and grants from NSF, NIH, many other government agencies, and numerous private foundations,” he says. Amidst this explosive growth, he is quickly mastering the nuances of his new position. Donald R. Lehman, executive vice president for academic affairs, says that he chose Hirshman for the job based on his extensive research experience with grants and contracts and his significant administrative experience as department chair at GW and at Colorado. “Elliot brings a number of strong attributes to the job,” he says. “He has an outstanding record of scholarly research, strong leadership skills with a vision, and experience working across the schools as chair or co-chair of two major task forces at the University level.” Hirshman is quickly putting those skills to work in his new position. “I’m excited to be on board,” he says.

On the medical side, The George Washington University Medical Center recently welcomed Anne Newman Hirshfield as associate vice president for health research, compliance, and technology transfer following a nationwide search. Hirshfield comes to GW from the University of Maryland, where she served for the past decade as assistant dean for research at the School of Medicine. She joined the University of Maryland in 1978 as assistant professor of anatomy, teaching gross anatomy and embryology and conducting research on female reproduction. Her extensive publication list includes more than a dozen books that she has written or co-written and more than 80 peer-reviewed journal articles and abstracts. She began to shift gears from researcher to administrator in the late 1980s, when, as treasurer of the board of The Society for the Study of Reproduction, she spearheaded the organization’s efforts to address various management and financial issues. “I really enjoyed the opportunity to help shape the future of an institution,” she says. “When the opportunity arose for me to help strengthen the research infrastructure at Maryland, I jumped at the chance.” A highlight of Hirshfield’s tenure at Maryland was bringing together a multidisciplinary team devoted to securing major facilities enhancement funding from the National Institutes of Health. The project resulted in $3.5 million to build the largest biosafety level 3 facility east of the Mississippi for the study of hazardous infectious agents and facilitated the building of a genomics center. She also received acclaim for developing an in-depth relational database for researchers and a more general Web-accessible compendium of research activities written in clear, non-technical language. Hirshfield looks forward to making an even greater difference at GW, where she plans to concentrate her efforts on expanding the research mission of the Medical Center by increasing the number of funded investigators, the extent of interdisciplinary collaborations, and the resources available to investigators to do their work. She also will be leading compliance and technology transfer activities. “I’m tremendously excited to be here,” she says. “This is a great institution with a proud history, and the Medical Center has assets already in place that will serve as a solid foundation for growing research: a splendid location, a new hospital, enthusiastic leaders who have made a strong commitment to research, some key core facilities, and a number of highly talented, dynamic investigators who are committed to enhancing the research environment. The potential is enormous.” —Jamie L. Freedman

Studying the Human Genome

As the science of genomics transforms the medical field, GW is taking a leading role in moving the discipline forward through a research center and a new graduate degree program. Genomics ResearchThe Catharine Birch McCormick Genomics Center officially opened last year after being established with a $7.2 million gift from the estate of William P. and Catharine Birch McCormick, MD ’37. A core University facility, the center brings together a number of GW departments engaged in genomics research—biochemistry, pharmacology, immunology, microbiology, computer science, biology, anthropology, and engineering—in an effort to centralize and extend the scientific genomics capabilities on campus. “Our McCormick Genomics Center is unique because of our location in the heart of Washington, and because of the directions we are planning for the center,” says Allan Goldstein, chair of GW’s department of biochemistry and molecular biology. “All of our partners are right here at our doorstep, Children’s National Medical Center, The Institute for Genomics Research, Howard Hughes, NIH, FDA, and the biotech corridors in Virginia and Maryland. We have all the elements here—a hospital, clinical practice, and strong research—to make this successful.” Genomics is the study of the genome—all the genes in an organism, as well as the relationship between genes and the function of cells and organs in health and disease. “Genomics is really genetic anatomy, or breaking diseases down into genetic components,” explains Tim McCaffrey, director of the center. “A goal of the center is to try to translate the information that has been discovered so that people can use it to understand disease and create new treatments.” One of only four women in her GW medical class, Catharine Birch McCormick left her entire estate to the University for the study of biochemical genetics. “She was way ahead of the curve in understanding what advances could be gleaned from genomics,” says Goldstein, who knew her well. “She understood before the science itself had been fully developed. We set up the center to be true to her legacy.” Pharmacogenomics ProgramPharmacogenomics—the study of how genetic variations affect the ways in which people respond to drugs, is an exploding field within genomics. Starting this fall, GW, partnering with Winchester, Va.-based Shenandoah University, will offer the nation’s first undergraduate program in pharmacogenomics. Combining the expertise of GW, with its medical school and strength in the basic sciences, and Shenandoah, with its school of pharmacy, the partnership provides an academic solution to an exploding need in the marketplace. Falling under the umbrella of personalized medicine, pharmacogenomics is the intersection of pharmacology and genetics. The cornerstones of this fast-growing field are tailoring drug therapies to individual patients based on their genetic makeup and predicting drug responses in patients, including the possibility of life-threatening side effects, via genetic testing. “Pharmacogenomics is going to revolutionize the way we practice medicine,” Goldstein says. “In the near future, we’ll all carry around a chip the size of a credit card containing our individual human genome, and when we go to the doctor’s office, they’ll plug it into a computer and then design a treatment that is right for each patient. More than 100,000 Americans die every year due to complications from medications that they take, because their genomes are a little bit different.” “Pharmacogenomics is a priority focus area for us,” McCaffrey says. “I believe that in the not too distant future, many drugs will be co-prescribed with genetic tests to gauge whether individual patients can take them safely and whether they will be effective. All the technology is there, and we’re eager to start applying it.” Students enter the GW/Shenendoah program as juniors and go on to earn a Bachelor of Science degree in health sciences with a specialization in pharmacogenomics. Based primarily at GW’s Virginia Campus, the program combines a focus on the basic sciences, taught by GW faculty members, with pharmaceutical courses taught by the Shenandoah faculty. The senior year curriculum doubles as the first year of Shenandoah’s Doctor of Pharmacy program, enabling students interested in completing a doctorate to graduate in seven instead of eight years. Students who choose to stop at the bachelor’s level will be well positioned to quickly land positions in the burgeoning biotechnology workforce. An inaugural class of 25 students is expected this fall. In subsequent years, the program is expected to double to 50 students annually in this eventual $2 billion industry. —JLF

The Soul of Rock ‘n’ Roll

Associate Professor of English Gayle Wald was awarded a National Endowment for the Humanities fellowship for 2005-06 as well as a GW University Facilitating Fund award to complete her book Music in the Air: The Life and Work of Sister Rosetta Tharpe (forthcoming Beacon Press) in December. Tharpe, a Pentecostal evangelist and gospel musician born in Arkansas, transitioned from playing on street corners and before small congregations in Chicago to collaborating with Cab Calloway in New York’s Cotton Club. She was a celebrated musician in the 1940s and ’50s and a lasting influence on artists such as Elvis Presley and Bonnie Raitt. Though many historians and journalists credit Presley with putting rock ‘n’ roll on the map, Wald says the inspiration of gospel pioneers such as Tharpe—who is largely excluded from traditional rock ‘n’ roll histories—was the driving force behind the quintessential American genre. “About eight years ago at an academic conference, I saw a video of Tharpe performing and was blown away by this woman who was in complete control of her audience, belting gospel lyrics and acompanying herself on an electric guitar,” Wald says. “She is an artist who, despite her talent and fame, fell between the cracks of history. The more I studied her, the more I saw that the contributions of African American women, the soul of the gospel music that inspired rock ‘n’ roll, have been largely been ignored.

Wald says her book will be the first dedicated entirely to Tharpe’s life and work. Most of the research she conducted for the book came from oral histories—it was a challenge to find interview subjects because most of Tharpe’s musical peers are deceased. “Most of the people with whom she collaborated have died, and she has no surviving relatives. I interviewed people who were at her recording sessions in various capacities, such as Gordon Stoker of the Jordanaires, Elvis’ back-up band, as well as people from her hometown and modern artists whom she inspired, such as Roseanne Cash.” Wald says the small community of musicians and fans who do know about Tharpe and her work are looking forward to the book’s release; Wald hopes to bring Tharpe’s history and influence to a wider audience. She will return to the classroom in the fall of 2006 to teach a dean’s seminar through the Columbian Research Fellowship, which she hopes will further illuminate Tharpe’s legacy. —Laura Ewald

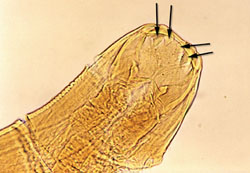

‘Hooking’ the HookwormIn February, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration gave “investigational new drug status” to a groundbreaking human hookworm vaccine developed by GW researchers. Clinical trials of the vaccine started at GW Hospital this spring.

There is no current vaccine to prevent hookworm disease, one of the most common chronic human infections, with about 740 million cases in areas of rural poverty in the tropics and sub-tropics. Professor Peter J. Hotez, chair of GW’s Department of Microbiology and Tropical Medicine, leads a team that conducts research, development, and pilot manufacture of the new vaccine as part of the Human Hookworm Vaccine Initiative. The initiative is sponsored by the Albert B. Sabin Vaccine Institute and funded by the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation; the project was recently renewed for the next six years with a $23 million grant. “Approval to begin safety trials was a major milestone for the human hookworm vaccine project,” Hotez says. “Our ultimate goal is to take this research to developing countries, where the vaccine will be tested with individuals who suffer from hookworm infection.” The infection is caused by parasitic worms that latch onto the inner layers of the small intestine with teeth-like projections, causing blood loss at the site of attachment. Hookworm disease is the iron deficiency anemia resulting from moderate and heavy infections. Because women of reproductive age and children have the lowest iron stores, they are most vulnerable to chronic hookworm blood loss. In children, chronic hookworm disease can cause physical growth retardation and cognitive impairment. The first phase of clinical research assesses the initial safety of the new vaccine as well as the immune system’s response to it—there will be several more years of trial and research before the vaccine is licensed for public use. In the fall, the Sabin Institute signed a memorandum of understanding with Brazilian federal and state production facilities for further clinical development and widespread manufacture of the vaccine—representatives of the Sabin Institute and GW visited the research and production plants. A team in Brazil is assembling baseline data in a rural area affected by the disease. Hotez says Brazil is among the few countries that is technologically capable of developing biological products and that also has a high endemic incidence of hookworm and pockets of extreme poverty. “Brazil has the technical capacity the project requires and intrinsic interest in the problem because hookworm is a public health threat in their nation,” he says. The data gathered in Brazil will be pooled with data from safety and tolerability trials in the United States to provide required groundwork for a wider clinical trial to gauge the efficacy and safety of the new vaccine. “This is the best and most substantive international collaboration I’ve ever had in 20 years of work in tropical medicine,” Hotez says. “We are working to alleviate the suffering of the poorest of the poor.” —LE An Anthropological Treasure

For more than a decade beginning in 1992, Assistant Professor of Anthropology Jeffrey Blomster led a team that examined pottery samples throughout Mexico and Central America. Elemental analysis supported their theory that the ancient Olmec—best known as the creators of colossal stone heads—synthesized Mesoamerica’s first unified iconographic system and disseminated it to other cultures. Blomster and his team believe the Olmec were the region’s first dominant civilization, a “mother culture” with significant influence on neighboring settlements. Since the 1940s, researchers have debated whether the Olmec were a mother culture in Mesoamerica or rather a “sister culture,” one of several influential peoples that developed simultaneously and contributed equally to one another’s lifestyles and ideology. Blomster and colleagues Hector Neff of California State at Long Beach and Michael D. Glascock of the University of Missouri say their findings support the priority of the Olmec in ideology and published a provocative report in Science in February. While their research supports Olmec priority in synthesizing a distinct ideology, the group emphasizes that the Olmec did not “create” other civilizations in Mesoamerica—they interacted with groups that had already achieved a certain level of complexity. The team conducted elemental analysis of more than 1,000 pottery and clay samples from San Lorenzo—the hub of early Olmec civilization—and six other sites that were prominent between 1200 and 900 B.C. during the “late formative” Olmec period of 1500 B.C. to 900 B.C. It was possible to link 725 archaeological ceramic samples with specific regions from which the clay originated. The results showed that all seven areas had Olmec-style pottery and figurines—some that were direct imports made in the San Lorenzo region and some that were replicas made from local clays. What most interested Blomster and his colleagues was that San Lorenzo had nothing from the other sites—and that none of the other sites had anything from one another, only from themselves and San Lorenzo.

Blomster says that the reproductions of Olmec pieces made in the other regions may not have had the same prestige or value as the imported pieces from San Lorenzo, a conclusion he formed because the original Olmec pieces were found in the higher status households of local leaders or people of wealth. “Higher-status houses at the other sites had more access to original Olmec pottery. The difference was in having the real thing versus obtaining a ‘knockoff,’” he says. While Blomster’s article sparked more debate between the mother-culture versus sister-culture theorists, he says he is pleased with the results and finds them to be conclusive evidence of the significant prominence and influence of the Olmec people. He says the presence of the original Olmec artifacts and their replicas in other locations implies more than the practice of exporting material goods; it indicates the exporting of cultural values and beliefs. —LE Two Share Trachtenberg PrizeFor the first time in the 14-year history of the Oscar and Shoshana Trachtenberg Prize for Research Scholarship, co-winners have been selected because members of the faculty selection committee simply could not make up their minds. One winner is Józef Przytycki, professor of mathematics, internationally known for his work on knot theory, a branch of topology aimed at understanding closed curves in three-dimensional space. Knot theory has diverse applications, including the study of DNA molecules and other proteins and twisted objects. According to his chair, professor Daniel Ullman, Przytycki “is at the peak of his career, working with the energy of a fanatical young prodigy but with the wisdom, breadth, and experience of a senior researcher.” A recommender from another university noted that he is “ ‘nonstop’ mathematics, always thinking about something, discussing it with whoever is nearby.” Przytycki, who earned his Ph.D. from Columbia University in 1981, has published over 100 papers and has made GW a mecca for knot theorists by organizing a research conference, Knots in Washington, twice a year. The co-winner of the prize is widely-known public intellectual Amitai Etzioni, who earned his doctorate in 1958 from the University of California at Berkeley. Etzioni served as president of the American Sociological Association in 1994-95 and has published an astounding number of books and articles. In 1990, he founded the Communitarian Network, a nonprofit organization dedicated to strengthening the moral, social, and political foundations of society. He is a prolific writer; in 2004 alone, he wrote three books (From Empire to Community, The Common Good, and How Patriotic is the Patriot Act?) and edited two more, while also producing numerous journal articles, book chapters, magazine articles, and op-ed pieces. GW President Stephen Joel Trachtenberg established the endowed fund for faculty scholarship in 1991 in memory of his late parents, Oscar and Shoshana Trachtenberg. The award is presented annually to a tenured member of the faculty to recognize excellence in scholarship.

|

© 2005 The George Washington

University

|

“This project has made me retrain myself as a

historian; I had to dig deep because the lives of women

like Tharpe are not well documented. No matter how rich

a legacy, a person can be forgotten.”

“This project has made me retrain myself as a

historian; I had to dig deep because the lives of women

like Tharpe are not well documented. No matter how rich

a legacy, a person can be forgotten.”