home | about | documents | news | publications | FOIA | research | employment | search | donate | mailing list

RELATED POSTING

The United States and the Chinese Nuclear Program, 1960-1964

January 12, 2001

Special Collection: Key Documents on Nuclear Weapons Policy, 1945-1990

China's First Nuclear Test 1964 -- 50th Anniversary

China's Advance toward Nuclear Status in Early 1960s Held Surprises for U.S. Analysts, Generated Conflicting Opinions about the Potential Dangers

Early RAND and INR Views Proved More Accurate than DOD's Office of International Security Affairs' Overwrought Scenario

The United States and the Chinese Nuclear Program, 1960-1964 Part II

National Security Archive Electronic Briefing Book No. 488

Posted - October 16, 2014

Edited by William Burr

For more information contact:

William Burr - 202/994-7000 or nsarchiv@gwu.edu

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Washington, D.C., October 16, 2014 – Fifty years ago today, on 16 October 1964, the People's Republic of China (PRC) joined the nuclear club when it tested a nuclear device at its Lop Nur test site in Inner Mongolia. For several years, U.S. intelligence had been monitoring Chinese developments, often with anxiety, hampered by the lack of adequate sources. Early on, opinions within the U.S. government varied widely -- from the views of RAND Corporation and State Department INR [Intelligence and Research] analysts who estimated that a nuclear-armed China would be "cautious" to the Institute for Defense Analyses, which saw "increase[d] risks for the United States and its allies that China will escalate hostilities to the point of initiating nuclear operations." As the Chinese nuclear test approached, the Defense Department's Office of International Security Affairs was alone in taking an alarmist view, projecting 100 million dead Americans in the event of conflict with China in 1980.

To mark the anniversary of the Chinese test, the National Security Archive and the Nuclear Proliferation International History Project are publishing, mostly for the first time, a wide range of declassified U.S. government documents from the early 1960s on the Chinese nuclear program and its implications. Documents include intelligence estimates and analyses reflecting efforts by U.S. intelligence to forecast when Beijing could and would test a weapon and what its diplomatic and military implications could be. During the summer of 1964, the discovery through satellite photography of a test site led to speculation that Beijing would soon stage a nuclear test. Other documents provide information on the State Department's decision to announce the Chinese test in advance — which it did on 29 September 1964 — in order to minimize its impact on world opinion.

Today's publication sheds light on the internal U.S. debate over the significance and implications of an initial Chinese nuclear capability. For example, the Institute for Defense Analyses saw increased risks that "China will escalate hostilities to the point of initiating nuclear operations, " while RAND Corporation analysts argued that "Chinese policy is likely to continue to be cautious and rational and to seek gains by exploiting those opportunities that represent acceptable levels of' risk." Similarly, the State Department's Bureau of Intelligence and Research (INR) believed that China would avoid "rash military action" because of its "relative weakness," and the risks of nuclear retaliation.

While President Kennedy had been worried enough about the prospects of a nuclear China to support contingency planning for preventive military action, by the time of the test the U.S. government had decided against such action. The arguments of an April 1964 top secret State Department study may have been influential: "the significance of [a Chinese nuclear] capability is not such as to justify the undertaking of actions which would involve great political costs or high military risks." Indeed, the author of that study noted that a preventive strike could miss important facilities and Beijing would continue to build the bomb. As views about Chinese caution became more typical, a report from the Defense Department's Office of International Security Affairs, prepared in early October 1964, was an outlier: based on the assumption of rapid growth of Chinese nuclear forces, it saw "very important and potentially dangerous consequences," including the need by 1980 to "think in terms of a possible 100 million U.S. deaths whenever a serious conflict with China threatens."

Nonproliferation concerns shaped U.S. thinking about the significance of a nuclear China.[1] The possibility that a Chinese nuclear capability would encourage decisions for national nuclear programs among China's neighbors raised some anxiety, especially with respect to India. Whatever the exact risks were, Secretary of State Dean Rusk observed in late 1963, "Our interest in a formal agreement on non-proliferation is 95% percent because of Communist China." A study produced in 1964 by theArms Control and Disarmament Agency shows how apprehension about a Chinese nuclear capability deepened interest in a global nonproliferation agreement as way to make "more difficult any national decision by non-nuclear powers … to acquire a nuclear capability."

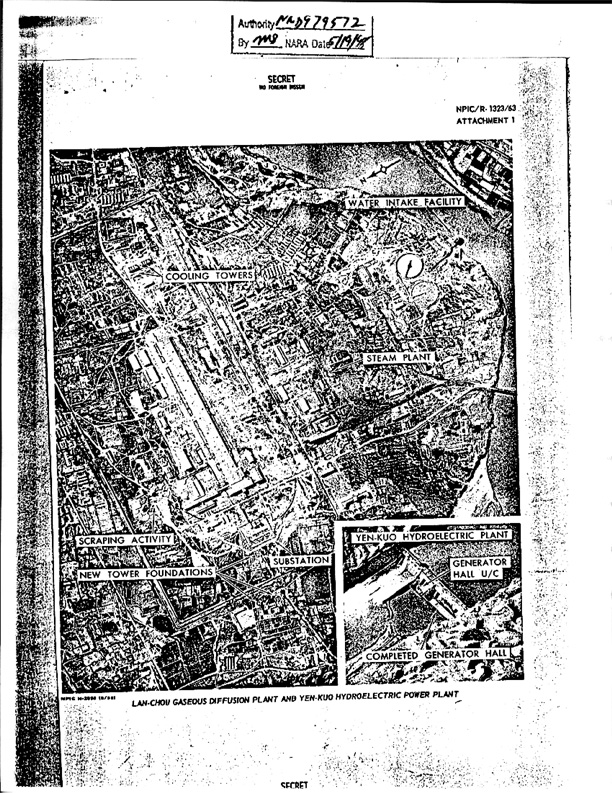

Before China conducted its test, Washington had expected that it, like nuclear powers before it, would test a plutonium-fueled device; the evidence at hand was thought to corroborate that. U.S. government officials and intelligence experts were startled when technical information collected by the Air Force showed that the device was fueled by highly-enriched uranium from a then-unknown source. An INR report prepared a few weeks after the test demonstrated how perplexed the U.S. intelligence community was over how Bejing had acquired the U-235. While a gaseous diffusion plant in Lanzhou had in fact produced the U-235,[2] U.S. intelligence did not believe that it had been in operation long enough to produce enough fissile material, but could not identify another possible source in China; moreover, it was "difficult to imagine that the Soviets would supply weapons-grade U-235."

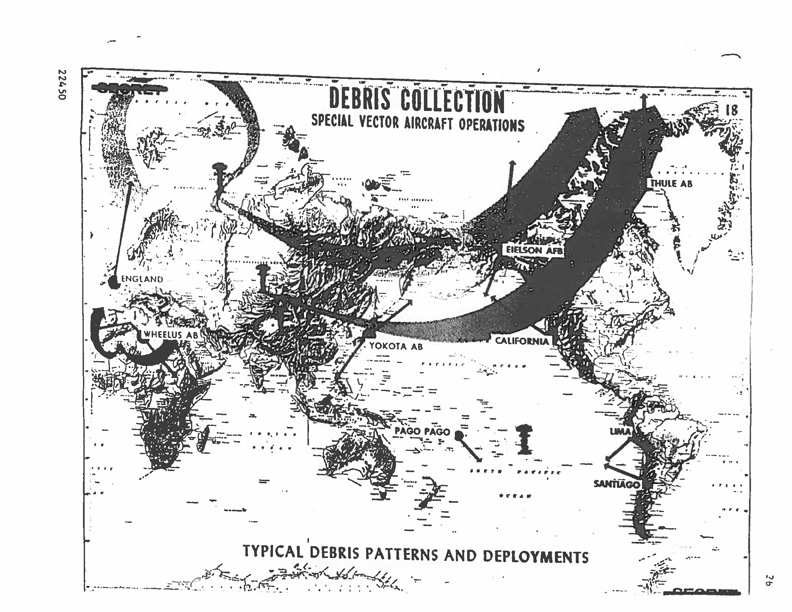

Other highlights of today's publication:

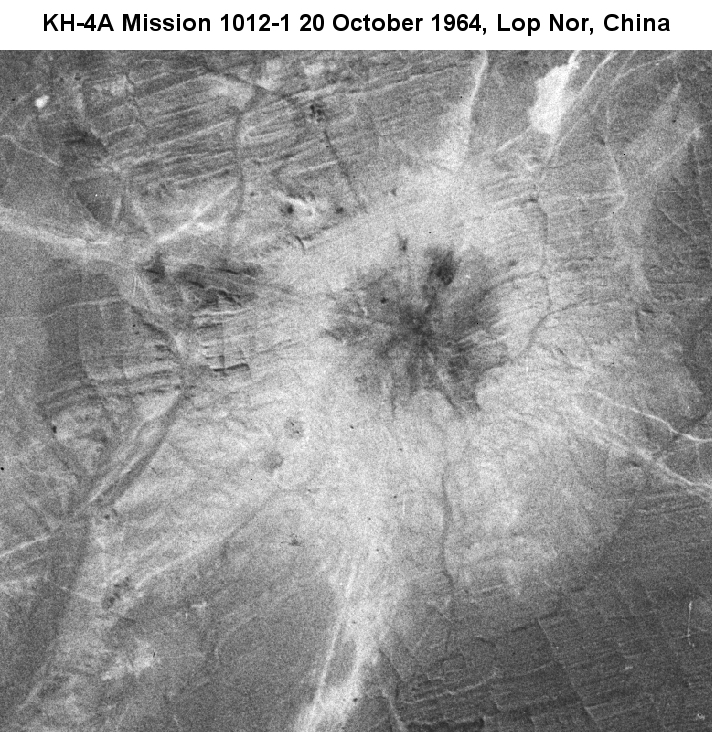

- Newly available Keyhole [KH]-4A satellite reconnaissance photographs of the Lop Nur test site, before and after the 16 October detonation, provided by Tim Brown of Talent-Keyhole.com.

- A State Department INR memo from July 1963 recounting the CIA's insistence that a Special National Intelligence Estimate include language about the possible impact of nuclear weapons on Chinese foreign policy that in effect meant: "we don't believe that something will happen, but if it does, we want you to remember we warned that it might."

- Joint Chiefs of Staff reports on the military and security implications of a nuclear China and proposals for military programs to counteract them.

- A hitherto unknown draft of a Special National Intelligence Estimate from late 1962 on the Chinese nuclear program that was abandoned for lack of new evidence.

- A major study prepared in 1963 by State Department official Robert H. Johnson on the potential consequences of a nuclear-armed China. Johnson did not believe this event would "alter the real relations of power among the major states," but the U.S. would have to find ways to reassure U.S. allies, in part to forestall "the possibility of development of independent nuclear capabilities by Asian countries (especially India)."

- An unofficial and unusual analysis prepared by INR analyst Helmut Sonnenfeldt. Taking a classic balance of power approach to the Sino-Soviet dispute, he argued that "our efforts should be to weaken the stronger and strengthen the weaker side in order to prolong a dispute which is to some extent debilitating to both." Accordingly, Sonnenfeldt suggested that it might be in the U.S. interest if China had "modest" nuclear forces which could threaten the Soviet Union, but not the United States.

The Chinese leadership sought nuclear weapons because of their experience in confrontations with the United States during the 1950s. In this respect, the 1955 Taiwan Straits crisis had central importance to Mao's decisions.[3] As he explained to the Communist Party Politburo in April 1956: "Not only are we going to have more airplanes and artillery, but also the atomic bomb. In today's world, if we don't want to be bullied, we have to have this thing." By then, the Chinese leadership had already made major decisions to launch a nuclear program. Moreover, they reached out to Moscow for scientific and technical assistance in launching a nuclear program. That Beijing wanted nuclear weapons, at least for basic security purposes, was well understood in Washington. According to a major State Department study from October 1963, a nuclear capability had "direct military value" to China as a deterrent against attack on its territory.

Today's posting follows up, and includes a few items from, an Electronic Briefing Book on "The United States and the Chinese Nuclear Program, 1960-1964," that the present editor and Archive senior fellow Jeffrey T. Richelson compiled in early 2001. That collection of estimates and studies coincided with an essay that International Security had recently published in its Winter 2000/2001 issue: "Whether to 'Strangle the Baby in the Cradle': The United States and the Chinese Nuclear Program, 1960-64." That article reviewed early U.S. government intelligence and policyanalysis of the Chinese nuclear program and the internal debate during 1963-1964 over the significance of a Chinese nuclear capability and whether it was necessary to initiate preventive action to forestall a Chinese nuclear capability.

I. Early Assessments, 1960-62

Documents 1A-C: The Intelligence Picture, 1960

A: Central Intelligence Agency, Article on "Chinese Communist Nuclear Weapons Program," Scientific Intelligence Digest, January 25, 1960, Secret, excised copy

B: Central Intelligence Agency, Article on "The Chinese Communist AE [Atomic Energy Program]," Scientific Intelligence Digest, May 31, 1960, Secret, excised copy

C: Charles C. Flowerree, Bureau of Intelligence and Research, Department of State, to John A. Armitage, "W arsaw Report on Chicom Nuclear Weapons Activities," Secret

Sources: Documents A and B: FOIA Releases; Document C: National Archives, Record Group 59, Department of State Records [hereinafter RG 59, Bureau of European Affairs, Office of Soviet Union Affairs Subject Files, 1957-1963, box 2, 1.3.4 Communist China

The U.S. intelligence establishment closely monitored Beijing's nuclear progress, although much remained unknown, including the scope of assistance that the Soviet Union had provided.[4] While the Chinese had three research reactors, maintained in part with Soviet aid, they could not produce sufficient quantities of fissile material for weapons and they would need to construct "special facilities to do so." By late 1960, U.S. government intelligence officials were well aware that Sino-Soviet tensions had led Moscow to cut off technical assistance. All the same, one State Department intelligence officer wrote that "there is little doubt … that the Chinese have attained a competence in atomic energy which would enable them eventually to produce a weapon of their own, even with no further Soviet assistance."

Document 2: Memorandum from General Lyman Lemnitzer, Chairman, Joint Chiefs of Staff, to the Secretary of Defense, "Strategic Analysis of the Impact of the Acquisition by Communist China of a Nuclear Capability," 26 June 1961, Secret

Source: John F. Kennedy Library, National Security Files, Robert W. Komer Files, box 410, China (CPR) Nuclear Explosion (folder 2 of 2)

The Joint Chiefs of Staff believed that a major world reaction to a nuclear China would be "fear that the chances of war had increased;" moreover, "there would be stronger pressure for the full acceptance of Communist China as a member of the world community" and greater pressures for "accommodation" with Beijing, with negative consequences for U.S. influence. Moreover, a nuclear-armed China would be more "truculent and militant." To counter this, the memo concludes, Washington should begin working with Allies on a program of "coordinated political, psychological, economic, and military actions."

Document 3: Central Intelligence Bulletin, article on "Communist China Nuclear Weapons Capability," October 14, 1961, Top Secret, excised copy

Source: FOIA release

The CIA's top secret daily publication ran a short article indicating Beijing's determination to get the bomb. It quoted Chief of the Peoples Liberation Army General Staff General Luo Ruiqing--Lo Jui Ching in Wade-Giles transliteration-as saying that China would not allow a nuclear test ban to "cheat" it from having a nuclear arsenal. Noting Sino-Soviet tensions over China's nuclear ambitions, the article contrasted Soviet concern about nuclear proliferation to a statement by Chinese foreign minister (presumably Chen Yi) that nuclear proliferation was not a concern because the chances of war would be reduced if more countries had nuclear weapons.

Documents 4A-D: "Study PACIFICA" Reports by the Institute for Defense Analyses, International Studies Division

A: "The Communist Chinese Nuclear Threat: Warheads and Delivery Vehicles," Study Memorandum No. 17 by Donald Keesing, May 9, 1962, Secret, excised copy, under appeal

B: "Military Implications of a Communist Chinese Nuclear Capability,"

Study Memorandum No. 14 by General John B. Cary, August 31, 1962, Secret

C: "Reactions to a Nuclear-Armed Communist China: Europe and the United Kingdom," Study Memorandum No. 12 by General "X" and Roderick MacFarquhar, September 15, 1962, Unclassified

D: Study Report No. Two, "The Emergence of Communist China as a Nuclear Power (Study PACIFICA, Final Report)," September 30, 1962, Secret, Excised copy, under appeal

In 1961, the Pentagon made arrangements for the non-profit think tank, the Institute of Defense Analyses, to prepare a contract study, "Study PACIFICA," on the emergence of China as a nuclear power. The study produced a number of reports listed in appendix B of the "Final Report" [Document 5D, PDF pages 126-127]; many remain classified and the final report has been heavily excised. Nevertheless, the "Military Implications" study by Air Force General John Cary was declassified in full and his conclusions may have influenced the PACIFICA final report. Citing estimates that Beijing would stage its first test sometime in the next two years, Cary saw dangers from a Chinese nuclear capability: it will " increase risks for the United States and its allies that China will escalate hostilities to the point of initiating nuclear operations; for China, that it may misread relative strengths and thus overplay its hand, and that the vulnerability of its nuclear forces may invite US counterforce operations." Moreover, a nuclear China, especially after the first test, "will create political and psychological influences that could materially weaken the military position of the United States and its allies in Asia."

To counter an emerging threat, Cary proposed a regional deterrent force that would be "plainly capable of devastating" China, without threatening the Soviet Union (which he assumed would continue to have strained alliance relations with Beijing). Such a force could "deter overt aggression …, permit the United States to impose ground rules, within limits, if aggression occurs; and minimize the risk of escalation uncontrolled by the United States." Among other recommendation was a capability for a "rapid US local response" that could control Chinese escalation and "minimize pressures for active Soviet support of Chinese military operations."

II. Estimates and Their Implications 1962-1963

Document 5A-B: The SNIE That Never Was

A: [ Name Excised] Deputy Assistant Director of National Estimates, Central Intelligence Agency, to Allan Evans (INR) et al., "SNIE 13-6-62: Implications of Communist China's Acquisition of a Nuclear Weapons Capability," October 9, 1962, Secret, Excised copy

B: Acting Deputy Assistant Director National Estimates, Central Intelligence Agency, to U.S. Intelligence Board, Special National Intelligence Estimate 13-6-62 Central Intelligence Agency, "Communist China's Nuclear Weapons Program," December 14, 1962, Top Secret, Draft, excised copy, under appeal

Sources:A: FOIA release; B: RG 59, Records of the Policy Planning Staff for 1962, box 232, China

By late 1962, the intelligence community had published several estimates of China's nuclear weapons potential. A National Intelligence Estimate completed earlier in the year suggested that Beijing could test a plutonium device by early 1963, but found it "unlikely that the Chinese will meet such a schedule." It was more likely that the first Chinese test would be "delayed beyond 1963, perhaps by as much as several years." Later in the year, at the specific request of the State Department, the CIA's Board of National Estimates drafted Special National Intelligence Estimate 13-6-62, which found that the "evidence is not now adequate to make a confident judgment about the likely date of a first nuclear test in China." It could "occur as early as 1963," but "we believe that it is more likely to occur some years later." The Air Force strongly dissented, arguing that China was "likely to conduct [its] first nuclear test in 1963-1964." This estimate remained in draft form, never finalized by the U.S. Intelligence Board, in order "to await further evidence" [See document 10 below].

Documents 6A-C: U.S. Air Force Project RAND Reports:

A: R.L. Blachly et al., Briefing, "Implications of a Communist Chinese Nuclear Capability: A Briefing," August 1962, RM 3264-PR, Confidential

B: R.L. Blachly et al., "A Study of the Implications of a Communist Chinese Nuclear Capability," December 1962, R-411-PR, Confidential

C: B. F. Jaeger and M. Weiner, "Military Aspects of A Study of the Implications of a Communist Chinese Nuclear Capability," March 1963, RM-3418-PR, Confidential, excised copy

Source: FOIA requests

Created by the U.S. Air Force in the late 1940s, the RAND [for Research and Development] Corporation produced studies on a wide variety of topics for that service.[5] In a briefing at Air Force headquarters, and a follow-on report, RAND analysts drew a nuanced picture of a nuclear-armed China: "Chinese policy is likely to continue to be cautious and rational and to seek gains by exploiting those opportunities that represent acceptable levels of risk." Nevertheless, a nuclear China "will adversely affect U.S. alliances and military posture in Asia and … generate pressures on U.S. freedom of action in the area." To compensate, the analysts proposed "the designation and maintenance in Pacific area of U.S. nuclear forces explicitly targeted for China and capable of flexible and selective employment against a wide range of Chinese aggressive actions."

A follow-up report from March 1963 analyzed three hypothetical military conflicts with China, two involving Taiwan and the Taiwan Strait, a third involving a Chinese nuclear attack on U.S. bases in East Asia. One conclusion was that Chinese "nuclear or high-level nonnuclear campaigns would involve very high risks on their part." For example, in the instance of a Chinese nuclear campaign against Taiwan, a U.S. counter-attack by augmented theater nuclear forces could "reduce the Chinese offensive capabilities to a very low level."

Document 7: Central Intelligence Bulletin, article on "Communist China-USSR- Nuclear Capability," March 2, 1963, Top Secret, excised copy

Source: FOIA release

This internal CIA article reports on a statement by what appears to have been a Soviet official that included an estimate that China would have a "plutonium weapon" in a few years, and that Chinese leaders believed that nuclear war would destroy capitalism, enabling "Chinese survivors to build a new world." The Soviet Union had taken "extraordinary measures" to convince the Chinese otherwise and had cut off nuclear assistance, the statement added, which did not information on how to build a gaseous diffusion plant for the enrichment of uranium.

Document 8: Executive Secretariat, U.S. Department of State, "The Secretary's Staff Meeting, 9:15 a.m. (Wednesday)," May 1, 1963, Secret

Source: RG 59, Executive Secretariat Briefing Books, Reports, and Minutes, box 1, Secretary's Large Staff Meetings 1963

During Dean Rusk's daily staff meeting, INR official George Denney reported that U-2 photographs (probably taken by Taiwanese pilots[6]), had "confirmed the existence of an atomic reactor in North China, capable of producing sufficient radioactive material for a few nuclear weapons annually." This was a reference to the Baotou (Pao-t'ou) site, which included a small power reactor. According to Denney, this finding "confirms existing intelligence estimates that the Chinese would be capable of detonating a small nuclear explosion by the end of 1963." It was this discovery that encouraged intelligence analysts to assume that the Chinese were likely to test a plutonium device.

Document 9 : Memorandum from George C. Denney, Jr., Bureau of Intelligence and Research, to Secretary of State, "Probable Consequences of a Chinese Communist Nuclear Detonation," INR Research Memorandum R-17, May 6, 1963, Secret

Source: RG 59, Bureau of Far Eastern Affairs, Assistant Secretary for Far Eastern Affairs Subject, Personnel, and Country Files, 1960-1963, box 21, CSM-Communism.

This report assessed the implications of a Chinese nuclear capability for Beijing's diplomatic and military posture, and for China's East and South Asian neighbors. Like the RAND analysts, INR maintained that China would avoid "rash military action" because of its "relative weakness," the risks of nuclear retaliation, and the "uncertainty" of Soviet support in a confrontation with Washington. To avoid losing support in the Third World, China "will attempt to pose as a peaceful, benevolent and powerful supporter of Afro-Asian aspirations for independence and peace." Nevertheless, China could make "political-military probes when and where it believes there are soft spots in the local situation" and in U.S. resolve.

Analysis of country reactions varied. For example, in Taiwan, a Chinese nuclear test "would probably produce a sense of shock and setback in Taiwan even though the leadership had discounted the event in advance and taken steps to offset its impact." In Japan, a "detonation will not come as a complete shock" but the reaction "is certain to be one of apprehension, disapproval and disquiet." While Beijing would like to move Japan toward neutralism, the Japanese were unlikely to "revise … defense policy or the relationship with the United States."

Document 10: Richard T. Ewing to George C. Denney, Jr., "SNIE 13-2-63: Communist China's Advanced Weapons Program," July 23, 1963, Top Secret

Source: FOIA release

With the evidence about Baotou (see Document 8), the intelligence community moved ahead in finalizing a new Special National Intelligence Estimate on the Chinese nuclear program — SNIE 13-2-63 — which it approved on July 24, 1964. But the day before, all the i's had not been dotted and INR staffer Richard Ewing provided some background and an overview of issues that the U.S. Intelligence Board would settle the next day. Ewing noted that the estimate was "the most optimistic plausible view" because in private most of the intelligence representatives were "more conservative about the timing and scheduling of [Beijing's] programs."

Whatever the analysts actually believed, their estimate forecast that a plutonium device could be tested by early 1964. This was based on an estimate that the recently discovered Baotou reactor could not have reached criticality before late 1962 and that it would take nearly two years to produce spent fuel and process it into plutonium. While U.S. intelligence recognized that China was building a gaseous diffusion facility at Lanzhou, the analysts did not believe that it would be large enough to produce U-235 for a nuclear test device.

Ewing recommended that the State Department press for the removal of paragraph 27, which held that "on balance," the intelligence board believed that the Chinese leadership would "react rationally" to their nuclear achievements, but "we do not exclude the possibility" that it could "embark on radical new external courses." This was a "saving" paragraph, Ewing observed, so that the intelligence community could say "we don't believe that something will happen, but if it does, we want you to remember we warned that it might." Ewing believed that CIA Director John McCone would resist removing the paragraph and it, or some version of it, survived.

Documents 11A-C: Working with Moscow

A: National Security Council Staff, "Briefing Book on US-Soviet Non-Diffusion Agreement for Discussion at the Moscow Meeting," circa June 12, 1963, Top Secret, Excerpts

B: Entry for 21 June 1963, Journals of Glenn Seaborg, Confidential

C: Memorandum from Thomas L. Hughes, INR, to Secretary of State, "Soviet Attitude toward Chinese Communist Acquisition of a Nuclear-Weapons Capability," September 11, 1963, Secret

Sources: A. John F. Kennedy Library, National Security File, Carl Kaysen Files, box 276, Nuclear Energy Matters, Nuclear Diffusion Briefing Book, Volume I on US-Soviet Non-Diffusion Agreement 6/1963; B: Declassification request to Department of Energy; C: RG 59, Policy Planning Council Records, 1963-1964, box 250, China

Moscow's thinking about a Chinese nuclear capability was of great interest to the Kennedy administration, in part because of the hope that the developing Sino-Soviet split could lead Moscow and Washington to reach a nuclear nonproliferation agreement and possibly team up to take joint action against the Chinese project. Toward that end, a briefing book prepared for the use of U.S. negotiators in talks with Soviet leaders on the test ban and nuclear proliferation issues included a paper, "Aborting the ChiCom Nuclear Capability," which directly raised possibilities for joint action, although Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev refused to single China out.[7]

The interest in joint action with the Soviets surfaced in a White House meeting recounted in the journals of Atomic Energy Commissioner Glen Seaborg. The meeting focused on the test ban negotiations with the Soviet Union and forthcoming talks in Moscow to be led by Under Secretary of State for Political Affairs W. Averell Harriman. According to Seaborg's account the discussion turned to China-which had refused to support a test ban treaty-when President Kennedy asked how the United States might handle that subject in the Moscow discussions. Reflecting ongoing discussions of the possibility of working with Moscow against the Chinese nuclear program, William C. Foster, the director of the Arms Control and Disarmament Agency, confidently observed that "if we could get together with the USSR, the Chinese could be handled even if it required an accidental drop on their facilities."

The reference to an "accidental drop on their facilities" was excised when the diary entry was first published in the Foreign Relations of the United States but the Department of Energy declassified it in response to a request for a new review of the document. An "accidental drop"-presumably a bombing- is an unusual form of arms control and just how the United States or even the Soviet Union could have staged such an event in the interior of China, where the nuclear facilities were located, is an extraordinary problem. The Kennedy Presidential Library indicates that a rough transcript of the meeting based on the original tape recording exists but is not yet declassified (whether the tape recording survives somewhere is unclear and rather mysterious). Therefore, it remains to be learned whether the transcript includes any discussion of the concept of "accidental drop." In any event, Foster's statement is one more piece of evidence that the Kennedy administration was interested in the possibility of taking military action against the Chinese nuclear program.

Document 12: U.S. Department of State Policy Planning Council, "Policy Planning Statement on A Chinese Communist Nuclear Detonation and Nuclear Capability," October 15, 1963, Secret

Sources: RG 59, Policy Planning Council Records, 1963-1964, box 275, S/P Papers Chicom Nuclear Detonation and Nuclear Capability Policy Planning Statement. 10/15/1963

During 1963, Robert Johnson, the State Department's leading expert on the policy issues raised by a Chinese nuclear program, prepared a major study on the impact and importance of China developing a nuclear capability. He started out with a several hundred page report; this version, about half the length, was widely circulated in the national security bureaucracy (Johnson prepared a shorter version for senior officials). Like INR and RAND analysts, Johnson assumed that a nuclear-armed China would act prudently and that a "regional" nuclear capability had "direct military value" to China as a deterrent against attack on its territory. While U.S. nuclear power would continue to deter China, Beijing could "be expected to continue to test from time to time through limited military pressures, the level of the U.S. commitment and response in Asia."

Johnson did not believe that the emergence of a nuclear China would in the near term "alter the real relations of power among the major states or the balance of military power in Asia," but he had concerns about the diplomatic and nuclear proliferation consequences. He recommended that the U.S. find ways to reassure allies in the region "to reduce the effectiveness of Chinese politico-military pressures" and to forestall "the possibility of development of independent nuclear capabilities by Asian countries (especially India)." In general, he recommended that the U.S. official reaction to a Chinese nuclear detonation "be sufficiently low key as not to suggest by sheer volume of activity and comment that the event is more important than is in fact the case."

Documents 13A-C: Planning for Preventive Action:

A: JCS Chairman Maxwell Taylor to Director, Joint Staff, "Operational Air Plan (China)," November 4, 1963, Top Secret

B: Assistant Secretary of Defense William P. Bundy to Deputy Secretary of Defense Gilpatric, "JCS Proposal Concerning Communist China," 13 December 1963, Top Secret

C: Deputy Secretary Gilpatric to Director, Central Intelligence, "JCS Proposal Concerning Communist China," 13 December 1963, Top Secret

Sources: A: RG 218, Maxwell Taylor Chairman Files, box 1, CMs; B and C: FOIA releases

President Kennedy's apprehension that a nuclear-armed China would become a dangerous threat produced a request by Assistant Secretary of Defense William Bundy for operational planning for preventive military action by the Joint Staff.[8] While contingency plans and proposals have not yet surfaced, it is clear that a JCS "Operational Air Plan" was not satisfactory to JCS Chairman Maxwell Taylor. Whatever happened to that plan remains obscure and the next month Taylor recommended that an interagency group explore counter-measures. While Bundy was not sure if anything was "really feasible," he suggested that the National Security Council "Special Group" on CIA covert actions look further into the matter. Accordingly, Deputy Secretary of Defense Roswell Gilpatric asked DCI John McCone to consider the problem.

Document 14: Helmut Sonnenfeldt note to Tom Hughes, April 4, 1964, enclosing paper, "The U.S. Interest in Communist China," October 14, 1963, Confidential

Source: RG 59, Office of the Counselor, 1955-77, box 2, HS Chron File July thru Dec 1963

Helmut Sonnenfeldt shared this unusual paper, written some months earlier, with INR colleague Thomas Hughes. Adopting a classic balance of power perspective toward the Sino-Soviet dispute, Sonnnenfeldt argued that "our efforts should be to weaken the stronger and strengthen the weaker side in order to prolong a dispute which is to some extent debilitating to both." Accordingly, it might be in the U.S. interest if China had "modest" nuclear forces which could threaten the Soviet Union, but not the United States. It was decidedly in the U.S. interest that Beijing and Moscow remain divided and also to aid the Chinese "at least to the point of assuring that they cannot be brought to heel by Soviet pressure." Moreover, Washington had an "interest in maintaining quiet direct channels of communication" with Beijing to convey important messages and as a basis for an eventual movement to "more normal relations." This kind of thinking would provide the basis for Nixon-Kissinger triangular diplomacy in the early 1970s when Sonnenfeldt was working on Kissinger's staff.

Document 15: State Department memorandum of conversation, "Proliferation of Nuclear Capability," December 4, 1963, Confidential

Source: RG 59, Records of Executive Secretariat. The Secretary's and Undersecretary's Memoranda of Conversations, 1953-1964, box , Sec Memcons. December 1963

During a conversation with Canadian Foreign Minister Paul Martin, Secretary of State Rusk declared that "Our interest in a formal agreement on non-proliferation is 95% percent because of Communist China." Unless China was party to such an agreement, it could "probably" not be ratified in the United States. Rusk would later change his thinking about China and a nonproliferation agreement, but concern about the proliferation impact of China's nuclear capability would persist for years.

III. 1964: A Test Looms

Document 16: Walt Rostow, Policy Planning Staff, U.S. Department of State, to McGeorge Bundy, "The Bases for Direct Action Against Chinese Communist Nuclear Facilities," April 22, 1964, enclosing report with same title, April 14, 1964, Top Secret

Source: LBJ Library, National Security File, Countries, box 237, China Memos Vol. I 12/63-9/64 [2 of 2]

This April 1964 report prepared by Robert Johnson may have had the effect of nipping in the bud, or at least forestalling, further serious consideration of unilateral U.S. or joint U.S.-Taiwanese preventive action, although interest in working with the Soviets would persist. The assumptions that underlay Johnson's earlier study of a Chinese nuclear program informed this evaluation of preventive action, which was closely coordinated with officials at the CIA and the Pentagon. According to Johnson, "the significance of [a Chinese nuclear] capability is not such as to justify the undertaking of actions which would involve great political costs or high military risks." For example, unless Beijing undertook blatantly aggressive military action, a U.S. attack on China's nuclear facilities "is likely to be viewed as provocative and dangerous and will play into the hands of efforts by [Beijing] to picture U. S. hostility to Communist China as the source of tensions and the principal threat to the peace in Asia." Moreover, Chinese propaganda could effectively portray a U.S. attack as "a racialist effort by the U.S. to keep non-white countries in a state of permanent military inferiority."

Another problem was deficient intelligence on Beijing's nuclear program. Thus, "even 'successful' action may not necessarily prevent the ChiComs from detonating a nuclear device in the next few years." If an attack missed some installations and "Communist China subsequently demonstrates that it is continuing to produce nuclear weapons, what is likely to be the reaction to the half-finished U.S. effort?" For Johnson, the only legitimate way for Washington to act against the Chinese nuclear program was if Beijing attacked a U.S. ally in East Asia.

Document 17: Director of Central Intelligence to U.S. Intelligence Board, Special National Intelligence Estimate 13-4-64, "The Chances of an Imminent Communist Chinese Nuclear Explosion,"26 August 1964, Top Secret, Excised copy

Source: CIA Web site, "The China Collection"

Photographs taken by the Keyhole satellite indicated that Beijing had prepared a site at Lop Nur in Mongolia for testing a nuclear device. This new evidence necessitated a re-evaluation of the estimates for the timing of a Chinese test. The uncertainty about China's sources of fissile material persisted, for example, whether Baotao or possibly other reactors had produced plutonium in sufficient quantities. The analysts allowed the incongruity of bringing a "test site to a state of readiness … without having a device ready for testing," Yet, Lop Nur was "extremely remote" and "we might expect to see the Chinese take a long time in preparing this installation." Thus, the resulting estimate was hedged, with plenty of "saving" language: a test could occur within a few months, but "on balance, we believe that it will not occur until sometime after the end of 1964."

Documents 18A-C: The Soviet Estimate

A: Memorandum of Conversation by Ambassador Llewellyn Thompson, "Miscellaneous Matters," 11 September 1964, Secret

B: Memorandum for the Record by DCI John McCone, "Discussion with Rusk in his office Saturday, September l2th - 10:00 to 1l:30 a.m.," September 13, 1964, Secret, excised copy

C: Central Intelligence Bulletin, item on "Communist China: Soviets believe Chinese Communists could detonate nuclear device at any time," September 19, 1964, Top Secret, excerpts, excised copy

Source: A: RG 59, Records of Ambassador-at-Large Llewellyn E. Thompson, 1961-1970, box 21, Chron - July 1964; B. and C: FOIA releases

At the beginning of a conversation with Soviet Ambassador Anatoly Dobrynin, Ambassador Llewellyn Thompson asked about Moscow's estimate for the timing of a Chinese nuclear test. Dobrynin "replied without hesitation that the Soviets thought the Chinese could conduct a test at almost any time now." During a conversation with DCI John McCone the next day, Secretary of State Dean Rusk passed on Dobrynin's statement, noting that it represented a "departure" from remarks that Foreign Minister Gromyko had made some time earlier. Dobrynin's statement was cited in an article for the Central Intelligence Bulletin, although the source information was excised, for reasons that are not easy to understand. In their analysis of the Soviet comment, CIA analysts argued that the "weight" of U.S. evidence suggested otherwise — a test "after 1964" — unless Beijing had "an undiscovered reactor" that could supply plutonium.

Document 19: W.W. Rostow, Policy Planning Staff, to Secretary Rusk, "The Handling of a Possible Chinese Communist Nuclear Test," September 26, 1964, Secret

Source: RG 59, Policy Planning Council Records, 1963-1964, box 265, RJ Chron File July-Dec 1964

Within the State Department, the possibility that the Chinese would soon test a weapon was the subject of considerable discussion, in part due to the confident analysis of INR China expert Alan Whiting.[9] Dobrynin's statement may have had an impact and some officials believed that Beijing might even test a weapon as early as October 1, National Day; that possibility may have lent support for a high-level statement to "make clear that we are anticipating the possibility" of a Chinese test. What was of particular concern to Rostow was that when U.S. government officials spoke publicly about the implications of a Chinese test they were speaking from the same page. In this connection, he was apprehensive about hyperbolic views expressed by the Pentagon's Office of International Security Affairs. For example, Assistant Secretary of Defense John McNaughton wanted embassies and military commanders to use this language as a talking point: "A growing Chinese stockpile of atomic weapons will present an ever-increasing threat to the freedom and security of all nations."

Document 20: Department of State, "Transcript of Daily Press Conference, Thursday, September 29, 1964"

Source: RG 59, Records of Special Assistant to Under Secretary for Political Affairs, 1963-65, box 2, Psychological Preparation of Chinese Test 10/16/62

Following up on the suggestion of an anticipatory statement about the Chinese test, Rusk released one to the press on September 29, 1964: "an explosion might occur in the near future" and the U.S. would announce it when it took place. Rusk further stated that "the United States has fully anticipated the possibility of [China's] entry into the nuclear weapons field and has taken it into full account in determining our military posture and our own nuclear weapons." On background, the Department's press secretary declared that "from a variety of sources, we know that it is quite possible that a first Chinese nuclear explosion could occur at any time."

Documents 21A-C: Conflicting Intelligence

A: Executive Secretariat, U.S. Department of State, "The Secretary's Staff Meeting -- 9:15 a.m. (Wednesday)," September 30, 1964, Secret

B: Executive Secretariat, U.S. Department of State, "The Secretary's Staff Meeting -- 9:15 a.m. (Friday)," October 9, 1964, Secret

C: Executive Secretariat, U.S. Department of State, "The Secretary's Staff Meeting, 9:15 a.m. (Monday)," October 12, 1964, Secret

Sources : RG 59, Executive Secretariat Briefing Books, Reports, and Minutes, box 1, Secretary's Staff Meetings, August-December 1964

The notion that Beijing could test on October 1 did not have the full support of the intelligence community; according to State Department's INR, the community "still estimates that a ChiCom nuclear explosion will not occur October 1." During the following weeks, INR monitored the latest intelligence. Although INR had information that China was passing out reports "that they will explode an atomic bomb either before or after the end of October," a few days later Beijing was denying any such thing.

Document 22: Office of International Security Affairs, Department of Defense, Memorandum, "China As a Nuclear Power (Some Thoughts Prior to the Chinese Test)," October 7, 1964, Secret

Source: FOIA release

A paper prepared at the Defense Department's Office of International Security Affairs provides an example of the overstated language and analysis that had concerned State Department officials: by 1975, China would have an "intercontinental capability" with the "the power to destroy San Francisco, Chicago, New York and Washington" and "threaten all of Europe," the paper declared. By 1980, Chinese nuclear capability should reach the point "where it will be necessary to think in terms of a possible 100 million U.S. deaths whenever a serious conflict with China threatens."[10] Nevertheless, some may find the language prescient; for example, "China is determined to gain status as a world power, primarily by reducing U.S. power and influence in Asia and the Western Pacific."

IV. The Test and Its Aftermath

Document 23: State Department Policy Planning Staff, "Implications of a Chinese Communist Nuclear Detonation and Nuclear Capability," October 16, 1964, Secret, with "Statement by the President on Chinese Communist Detonation of Nuclear Devices" attached

Source: RG 59, Policy Planning Council Records, 1963-1964, box 250, China

Written when word of the test reached Washington, this paper summed up the then prevailing State Department view that an initial Chinese nuclear capability would not change the "real relations of military power in East Asia." Further, "the great asymmetry in ChiCom and US nuclear capabilities and vulnerabilities makes Chicom first use of nuclear weapons highly unlikely against Asian nations." A statement issued by President Johnson the same day was calm and included the assurances that State Department officials believed were necessary to prevent overreactions in East Asia and elsewhere.

Document 24: Lindsay Grant memorandum to Assistant Secretary of State for Far Eastern Affairs William Bundy, "Policy Implications of Far Eastern Reactions to CCNE," October 23, 1964, Secret

Source: RG 59, Subject-Numeric Files, 1964-1966, DEF 12-1 Chicom

Except for Taiwan, "no panic" emerged in East Asia following the test, possibly owing in part to earlier U.S. government efforts to prepare public opinion and governments in the region for an eventual Chinese nuclear capability (for examples, see documents 4 and 14 In The United States and the Chinese Nuclear Program, 1960-1964)

Document 25: U.S. Embassy Taiwan telegram 1980 to State Department, October 23, 1964, Secret

Source: RG 59, Subject-Numeric Files, 1964-1966, DEF 12-1 Chicom

The official reaction of the Chiang Kai-shek regime to the Chinese test was so acute that high-level opinion crystallized around the need for a preventive attack on the mainland, with U.S. support, before Beijing had developed its nuclear capabilities. The embassy saw the test as a "severe blow to the leadership" in Taiwan.

Document 26: Memorandum from CIA Director to [Executive Director] Lyman Kirkpatrick, "Reaction to CCNE," October 29, 1964, Secret

Source: CREST

A conversation with former Pentagon official Jerry Johnson raised DCI McCone's concern about exaggerated interpretations of China's nuclear capabilities — for example, the Air Force view that Beijing's missile delivery capability was "imminent."

Document 27: Memorandum on Minutes of Meeting, "Next Meeting of the Committee on Nuclear Weapons Capabilities," October 30, 1964

Source: RG 59, Executive Secretariat, Records relating to the Committee of Principals 1964-1966, box 2, Committee of Principals - 1964 August through December.

During this wide-ranging discussion of the Chinese test, Ambassador Llewellyn Thompson mentions that Secretary Rusk "was disappointed at the lack of opprobrium in world reactions to the Chinese Communists' nuclear explosion." Topics discussed by the Committee on Nuclear Capability were the implications of the test, possible actions by the Indians and Japanese to offset the test's impact, and whether Washington should provide, possibly in concert with the Soviets, security assurances to other governments, including India.

Document 28: Thomas L. Hughes, INR to Secretary of State, "The Chinese Test," Research Memorandum RES-29, November 2, 1964, Secret

Source: Lyndon B. Johnson Library, National Security File, box 31, Nuclear Testing - China, Volume 1

This report shows how perplexed the U.S. intelligence community was over how Beijing had acquired the U-235 that had fueled the October 16 test device. While the gaseous diffusion plant in Lanzhou begun producing weapons-grade uranium by late 1963, U.S. intelligence did not believe it had been in operation long enough to produce sufficient fissile material. They could not identify another possible Chinese source; moreover, it was "difficult to imagine that the Soviets would supply weapons-grade U-235." By the time China staged the October 1964 test it had an on-going gas centrifuge program for enriching uranium, although more needs to be learned about the extent to which the program produced fissile material for the test.[11]

Document 29: Memorandum from William C. Foster, Director, U.S. Arms Control and Disarmament Agency, to Secretary of State, "Program to Limit the Spread of Nuclear Weapons," November 4, 1964, Secret

Source: NARA, RG 59, Executive Secretariat, Records Relating to the Committee of Principals, 1964-66. Box 2. Committee of Principals August through December 1964

This ACDA report, prepared for the newly-created, presidentially-appointed Gilpatric Committee, took into account the impact of the Chinese test on a program of international action to check the proliferation of nuclear weapons. Against the backdrop of concern that the Chinese test would put other countries under "increasing domestic pressure" to launch national nuclear programs, ACDA called for U.S. action at the United Nations General Assembly "to develop the widest possible consensus favorable to an international agreement on non-proliferation." It would take some time, however, for the Johnson administration to develop a consensus in favor of such an agreement.

Document 30: Defense Intelligence Agency, "An Assessment of the ChiCom Ability to Produce and Deliver Nuclear Weapons," November 24, 1964, Top Secret excised copy

Source: Lyndon B. Johnson Library, National Security Files, Committee Files, Records of the Gilpatric Committee, box 5, China

In its assessment of China's capability to produce fissile materials and atomic weapons, DIA concluded that the facility at Lanzhou was the source of the U-235 and that China was undertaking an "extensive, broad-based nuclear weapons program."

Document 31: Analysis to John T. Conway, Director, Joint Committee on Atomic Energy, U.S. Congress, "Atomic Energy Commission Analysis of Chinese Nuclear Test," December 2, 1964, Secret, excised copy, under appeal

Source: National Archives, Record Group128, Records of Joint Committee on Atomic Energy, General Subject Files, box 15, Foreign Activities (China) Weapons Tests

This recently released and heavily excised Atomic Energy Commission report yields little information beyond the fact that the test was of an "implosion device." A pending mandatory declassification review appeal may elicit the substance of this document.

Document 32: Earle G. Wheeler, Chairman, Joint Chiefs of Staff, m emorandum for the Secretary of Defense, "A Military Appraisal of Chinese Acquisition of Nuclear Weapons," December 3, 1964, Secret, excised copy

Source: FOIA release, under appeal

Soon after the Chinese test, the Joint Chiefs of Staff provided their analysis of its significance to the Secretary of Defense. While they did not believe that the test had changed the military balance of power relations in East Asia, they did recommend changes in the U.S. military posture to take into account China's new capability.

Document 33: U.S. Air Force Technical Applications Center, "History of the Air Force Technical Application Center (AFTAC) 1 July-31 December 1964," Secret, excised copy, excerpts

Source: FOIA release

Created in the late 1940s, AFOAT/1 (later renamed AFTAC) secretly monitored foreign nuclear weapons programs and discovered the first Soviet atomic test in August 1949.[12] This official history gives a useful sense of the ways and means that AFTAC used to track various indicators produced by the Chinese test, from radioactive debris to electromagnetic pulse. Analysis of the debris samples demonstrated that HEU had fueled the test device.

Editors' note: Thanks to Scott Sharon for assistance with preparing this compilation.

NOTES

[1] For proliferation and other concerns about China, see also Francis Gavin, "Blasts from the Past: Proliferation Lessons from the 1960s," inNuclear Statecraft: History and Strategy in America's Atomic Age (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2012), 75-81, and Shane Maddock, Nuclear Apartheid: The Quest for American Atomic Supremacy from World War II to the Present (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2010).

[2] For the successful production of highly-enriched uranium at Lanzhou during 1963 and related activities, see John Wilson Lewis and Xue Litai China Builds the Bomb (Palo Alto: Stanford University Press, 1988), 98-105, 114-125, and 134-136. For further background, see Jeffrey T. Richelson, Spying on the Bomb: American Nuclear Intelligence from Nazi Germany to Iran and North Korea (New York: W.W. Norton, 2006), 148-153.

[3] Wilson and Litai, China Builds The Bomb, 34-49; Gordon Chang and He Di, "The Absence of War in the U.S.-China Confrontation over Quemoy and Matsu in 1954-1955: Contingency, Luck, Deterrence," American Historical Review 96 (1993): 1500-1524.

[4] For Soviet nuclear aid in the context of the changing Sino-Soviet relationship, see Zhihua Shen and Yafeng Xia, Between Aid and Restriction: Changing Soviet Policies toward China's Nuclear Weapons Program: 1954-1960, Nuclear Proliferation International History Project Working Paper #2 May 2012. See also documents on the Web site of the Woodrow Wilson Center for International Scholars on "Chinese Nuclear History."

[5] For a valuable study on the RAND Corporation's early years, see Fred Kaplan, The Wizards of Armageddon (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1983).

[6] For the role of Taiwanese pilots in flying U-2 missions for the CIA, see Chris Pocock, The Black Bats: CIA Spy Flights Over China from Taiwan, 1951-1969 (Atglen, PA: Schiffer Publishing, 2010).

[7] See Gordon Chang, "JFK, China, and the Bomb," Journal of American History 74 (1988): 1289-1310, for background on these developments, as well as Noam Kochavi's. A Conflict Perpetuated: China Policy during the Kennedy Administration (Westport: Praeger, 2002).

[8] For more on these developments, see Burr and Richelson, "Whether to 'Strangle the Baby in the Cradle': The United States and the Chinese Nuclear Program, 1960-64," 67-76. See also Maddock, Nuclear Apartheid, 153 and 234-237, and Kochavi, A Conflict Perpetuated, 214-233.

[9] Burr and Richelson, "Whether to 'Strangle the Baby in the Cradle': The United States and the Chinese Nuclear Program, 1960-64," 83-86.

[10] Contrary to the ISA apprehensions, during the decades that followed China developed relatively small ballistic missiles forces on the basis of a minimum deterrent posture. See Jeffrey A, Lewis, Minimum Means of Reprisal: China's Search for Security in the Nuclear Age (MIT Press, 2007).

[11] Wilson and Litai, China Builds the Bomb, 166. On China and the gas centrifuge, see R.Scott Kemp, "The Nonproliferation Emperor Has No Clothes: The Gas Centrifuge, Supply-Side Controls, and the Future of Nuclear Proliferation," International Security 38 (Spring 2014): 51-52.

[12] For the origins of AFTAC, see Charles A. Ziegler and David Jacobson, Spying without Spies: Origins of America's Secret Nuclear Surveillance System (Westport: Praeger, 1995).